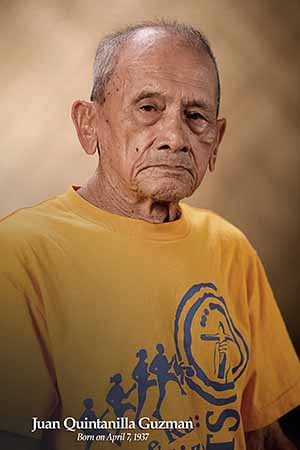

Fond memories of Sumai

Juan Quintanilla Guzman (1934 – 2021), affectionately known as “Major” spent his early childhood in Sumai and fondly remembered what his life was like there just before the war. He had been living with his grandfather’s brother, who was also named Juan, and his wife, Vicenta. The older couple could not have children of their own, so they adopted Guzman when he was five years old. He remembered it clearly, because he was already attending pre-school, which was called pre-primer at the time.

Guzman especially enjoyed his time at his family’s ranch in the Kabiyon (spelled Cabeyan in the 1940 Census) district of Sumai. He said there was even a song made about Kabiyon that was written by a man who was killed during the Japanese occupation. He happily sang the song as he remembered it:

Up on the hill of the village where I used to roam is my home in Kabiyon, where the roses bloom no more in my little låncho, ohh in my home on the hill of Kabiyon.

He added that the song was redone by Johnny Sablan, but he replaced Kabiyon with Hågat Town, and then again it was re-produced by an artist in Saipan, who replaced Kabiyon with Saipan.

Growing up in Sumai was quite an adventure for Guzman. One of his favorite memories happened just before the war came to Guam in 1941. He was seven years old and was a very curious child. Just before dark, he saw his grandfather leaving the ranch and started to follow him.

He kept chasing me back, but I held on to his sleeve.

Turtle stories recalled

He followed his grandfather to Orote Point and they climbed down steps that led to the beach. A torch made of bundled coconut leaves provided light at the beach, where a group of men were gathered.

I remember there was Alejandro Quan and Tun Juan Cruz … and there’s Tun Juan Concepcion … and my uncle, Juan Guzman.

The men had just caught a 300 pound turtle, and Guzman was amazed because he had never seen a turtle that big before. When he got closer, he realized that the men were drinking the blood of the turtle which shocked him. Later, he learned that the blood was used as medicine for strength. The men offered him some to drink, but he refused, because he was too young to understand and couldn’t get over the fact that they were drinking blood.

Sumai was a good place to catch turtle, Guzman recalled. He shared another story about a Japanese man named Mora, who had been living on the island before the war and was known as an excellent swimmer.

The story goes that when there’s a fiesta in Hågat or Humåtak, he’ll carry the turtle from Sumai. Imagine! He’ll swim all the way there with the turtle on his back.

Guzman’s mother’s brother didn’t know how to swim, and teasingly the teenagers in the village began to call him Mora. The name eventually stuck and became his uncle’s permanent nickname and family nickname.

Biggest impact was loss of Sumai

The biggest impact the war had on Guzman’s life was that it displaced his family from Sumai. They left when the Japanese attacked the village in 1941 and were never allowed to return. The attack was the first time Guzman remembers seeing a plane other than in pictures. He had been sent out to borrow a pot when he heard the plane, and then, he heard a loud “boom.” The first target that was hit was the petroleum company’s building, he said.

They never bombed the village. Only the Mobil, the Marine barracks, and the cable station.

He didn’t share much more about his life during the war, but instead focused on the final days of the occupation and what happened to his family after. Guzman remembers the day he left Manenggon, where he and most CHamorus had been forced to live at the end of the war. He said about four or five men in the Army had come to Manenggon in the late afternoon and told them to move out. Guzman was only 10, and as they were making their trek out of Manenggon, it got dark and he lost his family.

He walked with the Army men all the way to an area in Nimitz Hill. When they got there, there were two trucks – one going to Hågat and the other going to the cemetery in Hagåtña. He jumped into the truck going to Hågat and when he arrived in the village, his family was there. One of his aunties saw him and told the driver to hold on. Her husband, who had been killed by the Japanese, had retired from the Navy, thus she was very good at speaking English. Guzman got out of the truck and his family asked him where he had been.

Eventually, Guzman’s family moved to Apra in Sånta Rita-Sumai, where they built a shack and stayed until 1945. He said the commissioner at the time, Felix Pangelinan, was approached by a Naval commander, who said:

Well, Mr. Commissioner, I believe we’re gonna have to relocate you people to Hågat. And then the commissioner said ‘sir, you know the Sumai people … don’t want to go to Hågat and stay with the Hågat people.’

Thus, the commander identified government land and built homes on it for the people of Sumai to move to, which eventually became the village of Sånta Rita-Sumai.

Initially, the homes were built to house two families per home. As more houses were built in the village, the families partook in a raffle to decide which one of the two families would remain in their home, and which one would move into a new home. Guzman’s family, who had shared a home with the Munoz family, lost the raffle and had to move. Their new house was located right below where the Sånta Rita-Sumai church is today. Nearly a decade after the war had ended, Guzman’s family finally had a place to call home.

Editor’s note: Reprinted and adapted, with permission, from Guam War Survivors Memorial Foundation by Victoria-Lola M. Leon Guerrero.