Altar server at war’s beginning

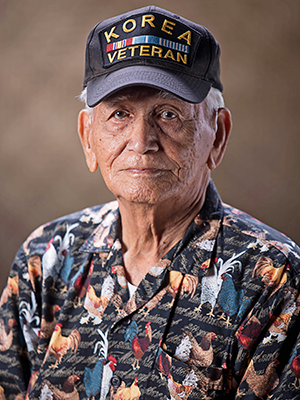

Fidel Toves Blas, (1932 – 2019) known to family and friends as “Dek,” was born in Hagåtña. His parents Concepcion Lujan Toves (Familian Capili) and Atanacio Albino Blas (Familian Haniu) had 12 children, and Dek was their third-born child.

That fateful morning when the Japanese bombed Sumai, nine-year-old Blas was at the Agana Cathedral, serving Mass as an altar server for the Feast of Santa Marian Kamalen.

Bishop Miguel Olano stopped the Mass and told everyone to go home right away. I was with John Sablan, Kin LG Iriarte, Ben Cruz, Mariano Cruz, and Antonio Baza. I lived next to the power plant in the ‘Bilibig’ area of Hagåtña and as I neared my home, I could see my mother standing by the road waving me to hurry up.

Fidel Toves Blas

It wasn’t the bombs that had frightened Blas, but rather the fear in the eyes of the grown-ups and the crying of his siblings because of the loud blasting of the nearby power plant.

That horn was blasting so loudly, and the warning lights on the smokestacks were flashing. Everybody was scared.

The family took whatever they could and traveled to a small ranch in Maite belonging to the Ada family. His father’s sister, Pilar, had married Manuel Ada, and so the Blas family accompanied them and other Ada family members to seek safety in Maite.

It took us all day long to walk from Hagåtña to Maite. I had to help carry my little brother Paul. That ranch was so small – good enough for four people – so we slept outside under the stars.

That was the first of many nights that he would sleep without a bed.

House dismantled and rebuilt in Agana Heights

Blas remembered staying in Maite for two or three months while his father dismantled the Hagåtña house and used those materials to build the family a home in Agana Heights, closer to a stream known as Etton.

It was a simple house with two rooms, but it became our home. And we had everything we needed.

He described the village they stayed in. There was Tutuhan (flatter ground), Tagigao (further inland) and Etton (hilly) areas in Agana Heights, Blas explained. They had the Fonte River and Etton and all kinds of fruits and vegetables. They did not starve.

Everything was shared or bartered

Blas also recalled how the families in the area became a close-knit community. There was no money exchange. Everything was shared or bartered. The Ada family made soap which was hung on a string next to the river, so anyone who needed it could use it and then leave it there for the next person. Blas’s father was good at preserving food. He would catch fish from the river or babui (pig), binaducha (deer) from the jungle. Whatever we could not eat or share because there was no refrigeration, he would salt and dry for later, Blas said. Salt was available in abundance because it was made by the Garrido family.

I think I might have rubbed shoulders with the taotaomo’na because the elders would make me go cut a piece of root from the nunu tree so they could make tea for their ailments. I was never scared and the spirits never bothered me because I always asked for permission. I could always tell where they lived because it was always clean under their trees.

This form of traditional medicine required steeping the root and mixing it with lemon or binaklen tuba (vinegar made from fermented coconut sap) to cure ailments and body aches.

When Blas attended the Japanese school in Sinajana, he was taught katakana (Japanese script) and the Japanese language.

They would often fill us with war propaganda, like, ‘you should forget about being rescued by the Americans. If they do land here, they will find nothing alive but the flies.’

Blas and his friends found humor in just about anything, as kids do, but once when he smiled impishly while bowing at the Japanese checkpoint located at the base of San Ramon hill, he was slapped for his impudence. Then he was hit again with a closed fist, which knocked his teeth loose. From that point on, Blas took other routes to and from Hagåtña.

I never went through that check point again.

Blas’s life continued almost normally for the duration of the war. During their free time, Blas and his “partner in crime,” Anselmo Untalan (also his first cousin) would wander up the hill in Etton to climb the tallest lemmai (breadfruit) tree to see what was going on.

I had never seen a plane in my life, so when we started to see and hear things, we went up to Etton and climbed the tree. We waved at the US pilot and pointed to where the Japanese bunkers were hidden. We probably scared that pilot to death seeing these little kids high up in the trees, but we cheered when he dropped the bomb where we pointed!

Blas said that his father never worked for the Japanese regime.

I used to wonder why my father was always gone. I never found out why until many years later when I read the article about the underground radio network during the war and that my father was a part of that group. I was so proud of him after reading what he had done.

Watched the action unfolding from a tree

Knowing that the tide was somehow changing, Blas and Anselmo once again braved Etton hill to perch up high in the lemmai tree and watch the action unfolding in the Philippine Sea before them.

From where I sat high up in the lemmai tree on the hill at Etton, I had a balcony seat watching the ship-to-shore bombardment of the US flotilla. I saw the flash of light and a puff of smoke from the ships’ guns and heard the loud whine of the shells and watched where they landed. At first, I thought they were aiming for Agana Heights, but kept missing.

One missile landed particularly close to the boys and Blas was grazed by shrapnel. They scrambled down the tree and skidded down the hill to safety.

Blas said that he also witnessed a wedding in the woods that evening. The Japanese had forbidden marriages, so Dolores Untalan and John Pangelinan wed secretly in the jungle. Blas was the altar server while a sympathetic Japanese priest officiated the marriage.

The following day, he accompanied the women up to Tai to farm and they were made to witness the beheading of CHamorus that the Japanese said committed crimes against the Imperial Army.

We were warned not to look away or do anything sudden or we would be next. I could not look. I closed my eyes just before the sword came down, but I felt it anyway.

The boys were told that Fr. Jesus Duenas was also executed in Tai. The impact of what they witnessed was contained until they left the area; then, as a group, women began wailing and falling down in fear and despair.

We started a prayer chain all the way back home. We kept saying the rosary over and over and over until we stopped walking.

That night, the Japanese herded all CHamorus on what has become known as the “March to Manenggon.”

By the time we reached the Tai area, everyone was on the road heading in the same direction. When we got to Manenggon, our family decided to camp a little ways up the hill instead of where everyone else was camped on the flatter ground.

Blas’s parents had secretly stashed some dried beef, so they did not starve. They were there for two days before Tun Juan Atoigue (Bobo) came running and yelling that the Americans were up on the hill looking around. Blas also remembers seeing Jorge Cristobal, a Navy man who had arrived with the landing forces (and was allowed by his commander to accompany the advance troops to look for his family).

Jorge was holding up a pack of Camel cigarettes and calling out for his family – the Cristobal, Casimiro and Haniu family. Looking around, Blas said that the Japanese guards seemed to have disappeared, so his family started to slowly edge away toward where Tun Juan and Jorge said the Americans were located. Blas remembers being loaded into a truck and transported down to Bradley Park (next to Pigo Cemetery) in Hagåtña by the Americans.

Blas also remembers being greeted by the American GIs with foods like canned corned beef hash and crackers. This memory is vivid for him because of the diarrhea that resulted from the sudden change in diet.

The following morning after the rescue, Blas recalls hearing the sound of military vehicles passing by. Curious and adventurous, young Blas was allowed to ride on a truck he said was called a “Dock” that went to Hagåtña then on to Radio Barrigada to deliver ammunition and return with a fallen soldier.

Three days later, Blas’s family was able to return to Tutuhan by truck. As they passed the Naval Hospital area, Blas looked up at his beloved Etton hill and was saddened by what he saw – absolute destruction. What was once lush greenery was now rubble and ashes.

I was thinking about how very blessed we were that we were moved away from there.

Editor’s note: Reprinted and adapted, with permission, from Guam War Survivors Memorial Foundation by Christine Dimla Lizama.