Education During the US Naval Era

School was not a new concept

When Captain Richard Leary arrived in Guam in 1899 to initiate American rule under the US Navy, he found a population that was relatively literate. The people had some experience with formal schooling although it was erratic and limited to favored families in Hagåtña. Francisco Olive reported in the 1880s that there were 18 schools in the Marianas Islands and an enrollment of 1,419 out of a population of 9,770.

Schooling was both religious and civic as eskuelan pale’ (priest schools or catechism) and eskuelan rai (king’s schools or government) operated side by side and sometimes in the same structure. Carano and Sanchez (authors of Guam history tome A Complete History of Guam) reported in 1964 that at the conclusion of Spanish rule 50 percent of the adult population was literate in Spanish and 75 percent in Chamorro. Many spoke English because of the trade with American and British whalers and many Chamorro men had been recruited as whalers themselves.

First two decades

Early Naval governors including Leary and his successor, Seaton Schroeder, made the case that a transformation needed to be made in the people. Schroeder noted that schools could help the people “attain the standards of civilization and morality that rule in the more enlightened parts of the world.” The actual goals were fairly limited. Governor EJ Dorn wrote that the basic aim was to “have the child of the present learn to express itself (sic) intelligibly in English and to know how much change is due from a $2 bill after a purchase at the traders.”

In addition to learning English, the military was concerned about sanitation and limited vocational pursuits. Governor George L. Dyer noted that one of the principle efforts of the school administration was to “insist upon the habits of cleanliness.” Economic objectives were tied to ranching and agriculture. Governor George R. Salisbury wrote:

It is the desire of the Governor to encourage the people of the island to live on the ranches, cultivate the soil, raise stock, poultry etc. and it is requested that the Teachers, Priests, Clergymen and all Civil and and Military Officials interest themselves in attaining these results.

The first two decades of Naval rule were marked by an effort to establish a system of schooling without educational experience or funds from the Navy. Governor Dyer issued General Order No. 80 that established compulsory school attendance for all children between the ages of eight and twelve. He also established an Officer of School Examiner who was authorized to issue fines. Without resources, Dyer used Naval station funds to pay military personnel to teach under the title “special laborers.”

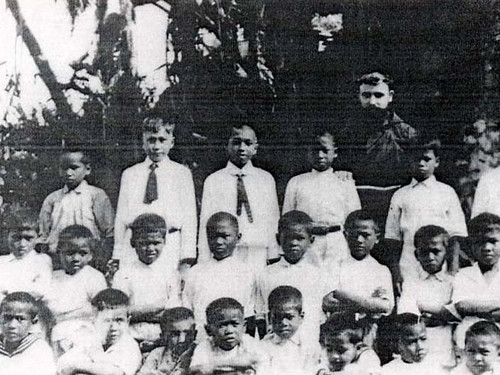

School Superintendent Albert Manley reported in 1909 that the system had an enrollment of 1,700 children, 29 native teachers, and 12 special laborers. Manley labeled the use of military personnel “unsatisfactory” and described the growth of the schools as being “built up in a moment, as it were, done with the ordinary revenues of the Island by discrete manipulation.”

Succeeding governors used the special laborer account and spent $5,000 of local revenues on education in 1912, $7,000 in 1917 and $14,000 in 1918. Governor Salisbury changed the compulsory school age to six through 12 in 1911 and instituted an excuse for distance program. If students lived more than two miles from a school, they didn’t have to attend. Using the unpopularity of going to school, he hoped to “encourage the people to live on their farms.”

Educational expenditures were at times subject to other priorities. In 1917, Governor Smith distributed more in bounties for killing rats ($10,000) than he spent on education ($9,640).

Major changes

Beginning in the early 1920s, major changes were made in the Guam Department of Education. Under the administration of Captain Adelbert Althouse and at the prompting of a Guam Congress petition to the Department of the Navy, Congress complained to the Navy department that the state of education was in its “crudest infancy.” Althouse removed Superintendent Jacques Schnabel and brought in Dr. Tom Collins who proceeded to make “sweeping changes” in the school system.

Collins developed a system of record keeping for the grading of the students and ensured that the schools were also “properly graded.” Collins required the preparation of daily lesson plans and a course of study that was based on a compilation of models from the Philippines, California, New Mexico, Washington and Washington DC.

A Normal School (teacher training) was established for the summer months and an evening high school was organized. A daytime high school (named George Washington) would not open until 1936.

Under Althhouse and Collins, congressional appropriations ranging from $12,000- $16,000 per annum began and counted for approximately 20 percent of the total government expenditures for education. This ended the surreptitious use of “special laborers” from Naval station funds. The changes were dramatic and well received although this new educational spirit also led to the burning of Chamorro-English dictionaries in 1922.

The Edward von Pressig dictionary was actually printed by the federal government and prepared by a Navy ensign in his spare time in the previous decade. But Chamorro was seen as the enemy of educational progress, even by Chamorro educators. One principal argued that citizens and teachers who do not improve their English skills are “really committing criminal deeds to the public and especially future generations.”

The nature of the changes was dramatic. Ten new schools were added between 1922 and 1926 and enrollment increased by 800 to 2,837. Teachers increased in number from 29 to 108 and approximately 25 percent of all educational expenditures were in education in comparison to the 10- to 20-percent figure of the first two decades.

Patriotism, the farm and Naval orders

In the 1930s, there was renewed emphasis on vocational education and an effort to build a secondary school system. Control and management over the system eventually shifted into Chamorro hands, but the curriculum and administrative style of the schools continued to reflect the concerns of Navy officers. They were concerned about cultivating a “forward look” while ignoring the possibility of political or social change.

Governor Willis Bradley recruited Wildred Newton as superintendent to make changes in the vocational program. Bradley thought the industrial schools were “exceedingly bad spots” in the system and that the agricultural school was “little better than a third-rate school garden.” Governor Alexander established adult education out of a concern that English is not the prevailing language of the people. He labeled this a “sad reflection on American leadership after thirty-five years of occupation.”

Secondary schools enrollment in grades 7th through 9th grew from 258 in 1934 to 384 in 1941. Admission to senior high school was generally limited to 30-35 students per year.

In pre-war Guam, the administrative style of the Navy was reflected in the management of the schools. The director of education was the governor. Under him, the “Head” of the school system was, by statute, a Naval officer appointed by the governor. Beginning in 1917, the “Head” was the Navy chaplain who was always Protestant in the very Catholic island. Under the “Head” was the superintendent who was required to be a “citizen of Guam” in 1940. It was a highly centralized system and the actual operation of the system was by the superintendent. In the early years, Manley and Schnabel served as superintendents. Their qualifications are unknown. Collins and Newton were two professionally trained occupants of the office. Simon Sanchez, a Chamorro, eventually became superintendent in 1940. By then, the system was operated and managed primarily by local people with local resources.

The rigid system of promotion and teacher ratings was kept in tact. The system did not allow for “social promotion” and students simply stayed in school until they were 12-years-old and then left. The lock-step nature of this system is reflected in the enrollment characteristics in 1938. Twelve-year-olds were distributed in various grades. There were forty-one in the 2nd grade, 136 in the 3rd grade, 182 in the 4th grade, and fourteen in the 5th grade. Teachers were subjected to “proficiency” reports and tested regularly themselves.

Officials wanted compulsory education but they wanted the education to not create unrealistic expectations or reduce the “agricultural spirit.” Officials wanted to make sure that Guam’s young men didn’t become “illustrados” and that the island not be burdened with a “semi-educated class of parasites who deem it beneath their dignity to engage in manual labor and aspire only to clerical and storekeeper jobs.”

Self discipline and citizenship were also part of the curriculum, but was more concerned with acquiescence than criticism. One researcher noted that due to the “anomalous political status of Guam” the terms good citizenship and character “have a different meaning from that found in the states.”

Training for citizenship and self-discipline meant patriotic recitations, calisthenics, drill teams and flag ceremonies not an analysis of the US Constitution or Declaration of Independence. Vocational education was defined as the “agricultural spirit” and a warning not to covet indoor jobs. Industrial fairs were really about agriculture. An emphasis on English and sanitation continued to be the other main goals of the system. “No Chamorro” rules were instituted, but as a practical matter Chamorro continued to be used as an adjunct language to teach children, particularly in the primary grades.

Education options

There were other schools and educational experiences on the island. Children of the elite were frequently tutored at home until secondary school. Everyone went to eskuelan pale’ led primarily by priests and young women. This was conducted in Chamorro and many children learned how to read in Chamorro before English.

The Guam Institute was a successful private school organized by Nieves Flores, a Filipino immigrant. The school was regulated by the Naval government through monthly visits. The enrollment was 109 in 1930 and 138 in 1940 and included the 12th grade just before the outbreak of World War II.

The American School was established for military dependents on a subscription basis. In 1930, there were thirty students enrolled in the American School and sixty-three enrolled in the two branches (one in Sumay) in 1940.

For the majority of the children, they were supposed to develop a “forward look” without clarifying what that forward look meant politically or economically. Those lessons came with the cataclysms that the island and the people underwent in the ensuing war, the Japanese Occupation and the return of the Americans in a new world. When the Japanese landed on 10 December 1941, changes would occur that would never take the island back to schools named Althouse, Gilmer, Maxwell, Leary or Root Agricultural School. Like the pre-war governors these buildings were named after, they were part of a bygone era that would never return.

Videos

For further reading

Albert, Francis Lee. “History of the Department of Education in Guam During the American Administration.” Guam Recorder 8, no. 7 (1931): 373, 378-386.

Althouse, Adelbert. Letter to the Secretary of the Navy, April 28, 1923. Naval Government Collection. Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam.

Carano, Paul, and Pedro C. Sanchez. A Complete History of Guam. Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle, Co., 1964.

Collins, Thomas. “Department of Education.” Guam Recorder, no. 4 (June 1924): 10-12.

–––. Letter to the Governor of Guam, 1923. Naval Government Collection. Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam.

Dorn, Edward J. “Our Administration in Guam.” Independent, 21 September (1911): 636-642.

Dyer, George L. “Annual Report of Naval Station, Island of Guam.” In Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Year 1904. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904.

García, Francisco Olive y. The Mariana Islands, 1884-1887: Random Notes. 2nd ed. Translated and annotated by Marjorie G. Driver. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1984.

Guam Congress. “Petition to Secretary of the Navy.” Petition, 1923.

“Is Education in Guam a Mistake?” Guam Recorder 1, no. 12 (February 1925).

Manley, Albert. Letter to the Governor of Guam, December 6, 1909. Naval Government Collection. Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam.

Torres, Joaquin. “Why I Study English.” Guam Recorder 2, no. 15 (May 1925): 78.