Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands in Guam

Table of Contents

Share This

Trust Territory Headquarters in Guam

For Guåhan’s neighboring Micronesia islands, their designation as the United Nations’ Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) under US administration was their pathway to self-determination and decolonization. Though the process was fraught with controversy, each of these islands self-determined its current political status. In contrast, Guåhan, also a US territory, played several key roles in administering the TTPI, including hosting its headquarters for nearly a decade and serving as a model in some ways for TTPI administrators. Yet, Guåhan has not had a clear path to self-determination and decolonization and remains a US colonial possession.

While both the former TTPI islands and Guåhan continue to be regarded as strategically important, their distinct political statuses have led to different ways this US valuation impacted their people. In particular, their status as a continued colonial possession has challenged the people of Guåhan in many ways, not the least of which has been their Indigenous connection to their homeland. I manaotao mo’na (CHamoru ancestors) considered their island the center of the universe, the place where all people and things were created, in stark contrast to the outsider perspective of a strategic, but small, far away, and isolated place, whose people deserve fewer rights and protections than others.

US Territories

From its inception as a nation, the US had territories, which were intended to become states of the union. However, islands such as Guåhan and Puerto Rico, gained as spoils from the 1898 Spanish-American War, were considered to be different territorial acquisitions than the US had previously experienced. These new insular areas had not been settled by US citizens of European ancestry who petitioned the US federal government for association, inclusion and statehood. Instead, they were wartime acquisitions with varied indigenous populations who US officials viewed as different ethnically, culturally, and otherwise.

Because of this outlook, a long series of court cases, known as the Insular Cases (1901-1922), was required to determine how the US should legally treat such territories and their populations. In the end, the Insular Cases developed a new political status for these islands, as unincorporated territories, not intended to be an integral part of the United States (as a state or district) and to which the US Constitution need not fully apply. The US Congress was deemed to have the authority to make all rules and regulations for administering these acquisitions and for determining their future political status. However, for half a century, the US Congress chose not to determine the political status of Guåhan and the human rights of its people, considering but quickly dismissing CHamoru pleas and petitions for civil rights and local self-government allowing the Executive Branch by default to institute Naval rule of the island.

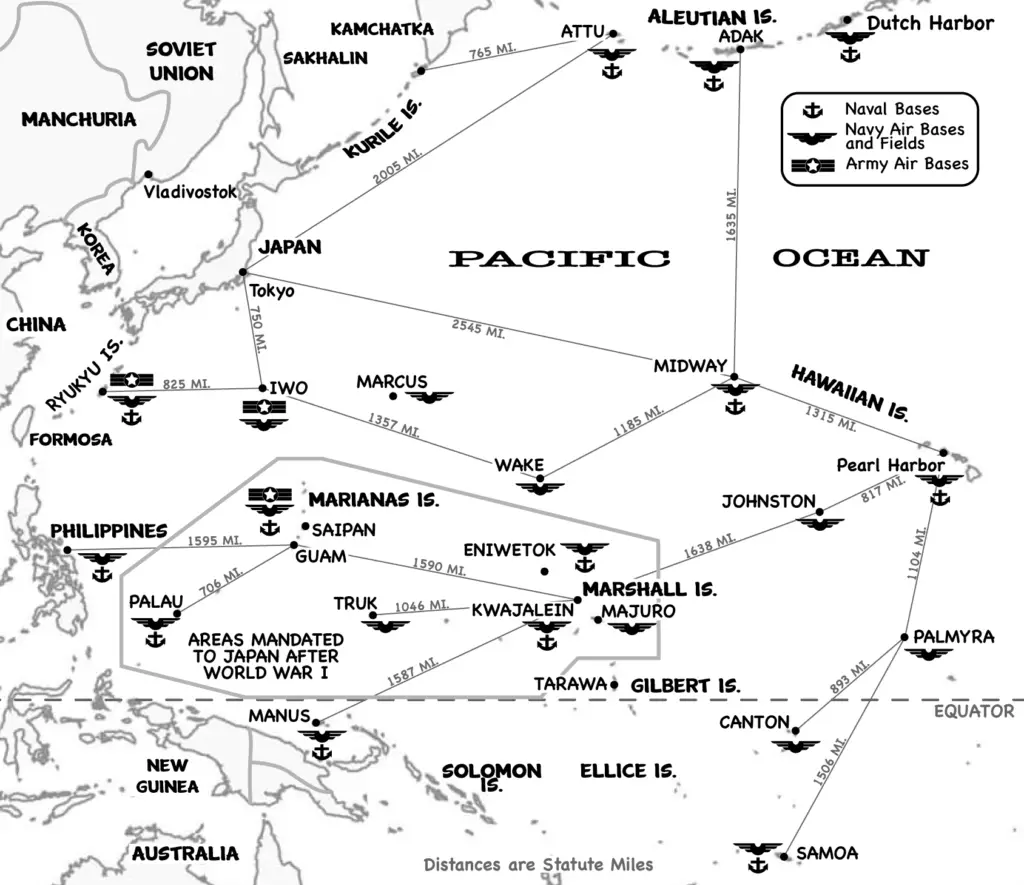

Since that time, the US has recognized two main types of territories—unincorporated ones like Guåhan that are considered possessions, and incorporated ones to which the US Constitution fully and directly applies, of which there is currently only one, the uninhabited atoll, Palmyra, off of the Hawaiian islands. However, for more than four decades, the United Nations (UN) also recognized the US as administrator of the TTPI comprised of the Micronesian islands that had been under Japanese administration for 25 years prior to World War II — all of Micronesia except for Guåhan, Nauru, and Kiribati (see map 1). In many ways, these different types of territories have intertwined histories and effective relationships. This holds true for the TTPI and Guåhan.

A Strategic Trust Territory

Late in WWII, Allied forces employed the strategy of island-hopping in the Pacific Theater in their fight against Japan. The US, as a chief Allied power, led the Island-hopping efforts beginning in the south in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Under US Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and General Douglas MacArthur, islands were selected for their strategic value in winning the war. Some were invaded and conquered, while many others were bypassed. In this way, throughout 1944, the Allies seized Micronesia from Japan and established a military government.

The US wartime government stayed in place for three years, until Japan surrendered (1945) and the US sought and secured a UN trusteeship status for the people of Micronesia in 1947. Of the 11 UN trusteeships formed after WWII, the TTPI was unique. While the social, economic, political development, and self-determination of the people were entrusted to all nations under UN auspices, the TTPI was the only trusteeship designated, at US insistence, as strategic. Specifically, as outlined in the TTPI trusteeship agreement, this meant:

In discharging its obligations under Article 76 a and Article 84 of the Charter, the Administering Authority shall ensure that the Trust Territory shall play its part, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, in the maintenance of international peace and security. To this end the Administering Authority shall be entitled:

- To establish naval, military and air bases and to erect fortifications in the Trust Territory;

- To station and employ armed forces in the Territory; and

- To make use of volunteer forces, facilities and assistance from the Trust Territory in carrying out the obligations towards the Security Council undertaken in this regard by the Administering Authority, as well as for the local defense and the maintenance of law and order within the Trust Territory.

Many of the actions taken by the US during this time have had far reaching and long-lasting consequences, some of which remain controversial and for which justice is still being sought. For example, while trusteeship obligations included the responsibility to promote the health and well-being of the people and to “protect the inhabitants against the loss of their lands and resources”, the US carried out 67 nuclear tests (1946-1962) in the Marshall Islands which caused the radioactive contamination of people, islands, and seas there, a toxic legacy that continues to be passed on generationally.

The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

The TTPI, commonly referred to in US documents at the time as the Trust Territory, was comprised of 3,000,000 square miles (often compared to the size of the continental US; see map 2), some 88,000 people, 96 island groups, and 2,100 islands in what were categorized at the time as three, loosely defined archipelagos—the Marianas, the Carolines, and the Marshalls. Specifically, the TTPI was comprised of the island groups which became the US Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; and the Freely Associated States of the Republic of Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia (Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae), and the Republic of the Marshall Islands.

Map: 1946 Pacific Bases

Location, Location, Location

In many ways, Guåhan’s history and people have been intertwined with the TTPI (see Table 1). Operations for the US military wartime government of the Micronesian region were directed largely out of Guåhan (1944-1947), which also served as the first TTPI headquarters while the Micronesian islands were administered by a US Naval Government (1947-1949). Even after the military government relocated the headquarters to Hawai’i, Guåhan continued to serve as a Field Headquarters (1949-1951).

This pattern continued when the TTPI was placed under the administration of the Department of the Interior (1951-1954). However, the UN had criticized the fact that the headquarters were outside the TTPI, stating that it needed, instead, to be located within the TTPI region. After all, Hawai’i was thousands of miles and a day’s travel away. The Department of the Interior debated where to relocate the headquarters for years, finally deciding on Guåhan.

While Guåhan was not the first choice for the new headquarters, it was within the same region as the TTPI and thus close to them. Further, US administration of the TTPI was shared for a time between the Department of the Interior and the US Navy (see Table 2). Locating the headquarters on Guåhan allowed for “maximum liaison and coordination of policies between the [TTPI] High Commissioner’s office and that of the Commander, Naval Forces, Marianas to promote administration of the trust territory as an integrated whole.”

Additionally, Guåhan had the requisite infrastructure—a modern capital city, a modern seaport, and modern commercial and military air bases that no other Micronesian island had. At the time, the infrastructure required for relocating the headquarters to the preferred area of centrally-located Truk (as Chuuk was then referred to by TTPI officials), was essentially non-existent and would have required millions of dollars that the TTPI did not have. It also would necessitate additional time to be developed, although it remained the proposed final location for years. Given these and other considerations, the headquarters were relocated to Guåhan and stayed there for nearly a decade (1954-1962).

In Guåhan, the TTPI headquarters were situated at the Hotel Tropics, a complex of wooden structures in the village of Maite, adjacent to the commercial airport and capital city of Hagåtña. This complex eventually became the Micronesian Village hotel, which has since been razed.

In 1962, when a CIA base in Saipan was closed and the Northern Mariana Islands were returned to the Department of the Interior’s civilian administration, the UN’s criticisms regarding the headquarter’s location were finally addressed by relocating it to what became its final location, to the former CIA facilities in Saipan. Within the TTPI, Saipan then had the most developed facilities, such as roads, docks, power and water systems, warehouse complexes, and housing for personnel.

Impacts of Guåhan serving as a strategic location for the TTPI

Guåhan has been consistently important to the US owing to its geographical location. It was seized by the US during the Spanish-American War, because it was well-located to serve as a coaling station for US Navy vessels. This contributed to Guåhan being administered by the US Navy.

On the one hand, Guåhan’s strategic location was largely why the US built up the island’s infrastructure and both of these ‘assets’ made Guåhan the preferred site of the TTPI headquarters and field headquarters over the years. On the other hand, this narrow strategic interest worked against the US Navy in determining which US agency should administer the TTPI. During the internal debate among the departments of Defense, State, and Interior over which would administer the TTPI, the Navy was highly criticized by former Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes and others for its ‘undemocratic’ administration of Guåhan. This critique was used to argue against a Naval administration of the TTPI.

Though Guåhan consistently served as a useful location for federal priorities and activities, that did not mean the island was included in many of those federal activities. Both positive and negative stories about the TTPI occasionally showed up in local newspapers, TTPI and Guåhan leaders attended some of the same events, and some members of Guåhan’s community worked for the TTPI. However, local leaders of the time don’t recall much interaction between the TTPI and the government of Guåhan. They do recall that TTPI operations didn’t seem very active at the time, an observation that reflects the policy priorities regarding the TTPI during the Eisenhower administration (1953-1961).

Operations and development funding was severely limited given the responsibilities required by trusteeship, little social or economic development took place, and the US essentially administered the islands as if they were a colonial holding. At the same time,the US was spending a lot of time, energy and money in the TTPI conducting nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands and carrying out covert CIA anti-communist operations from Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands.

Nevertheless, a number of social, economic, and political impacts resulted from the historic inter-relations between TTPI and Guåhan officials. Over the years, the island was the initial location of several TTPI programs, such as the interpreter’s school, the TTPI’s first high school (Pacific Islands Central), and the Marianas Area Teacher Training School. It also was the site for conferences, training, and inter-district meetings, including the first Trust Territory-wide meeting composed of Micronesians representing their respective islands. Students from the TTPI were sent to Guåhan to attend the newly formed trade and technical school and the Territorial College of Guam, which became the University of Guam. In this manner, Micronesian leaders and many others were introduced to Guåhan. Friendships were formed between participants in the TTPI programs, many of whom became leaders in their island communities, and the leaders and people of Guåhan. Many of these bonds are still remembered and maintained today.

Even after the TTPI headquarters were relocated to Saipan, political leaders from Guåhan carried out initiatives with TTPI officials. Guåhan Senator Richard F. Taitano, for example, was appointed Director of the Office of the Territories in the Department of the Interior by President John F. Kennedy (1961-1964). Taitano’s responsibilities included oversight of the TTPI and he was later appointed TTPI Deputy High Commissioner (1964-1966) by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Over the years, TTPI administrators invited Guåhan leaders to speak at various gatherings, some of whom, such as Guåhan’s Director of Administration, Joe T. San Agustin, were popular in this regard.

Regional leaders continued to formally work together when the 9th Legislature of Guåhan adopted a resolution to create an annual conference of legislators from the TTPI and Guåhan. For many years, Guåhan also served as the gateway to the TTPI for Micronesians, visiting UN officials, US Congressional delegations, TTPI staff, Peace Corps workers, and others. These visitors would land on Guåhan, perhaps carrying out business on the island, before venturing to carry out their duties in the TTPI. This interaction also allowed Micronesian leaders to observe aspects (both positive and negative) of Guåhan’s economic, social and political development, including possible political status options with the US. Many have said over the years that these observations led them to conclude that they did not want a territorial status with the US.

Another opportunity that interaction with the TTPI offered was a dialogue between the leaders of Guåhan and the Northern Mariana Islands to consider and work together toward the political reintegration of the Marianas archipelago, which had been partitioned as a result of the 1898 Spanish American War. In addition to unifying the CHamoru people who had been politically pulled apart for more than 50 years, some local leaders believed that their options for full self-government would be taken more seriously by the US if they had strength in numbers and a larger, unified archipelago. For a variety of reasons, their attempts to reunify the islands were unsuccessful. At the same time, Guåhan, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the rest of the TTPI had to resist and reject various US, UN and other outside visions of their future political statuses. The US as well as the UN pushed for the TTPI, composed of several distinct Micronesian cultures and languages, to work toward a singular, shared political status. Others proposed the possibility that Guåhan and even American Samoa should be part of the eventual singular political status of the TTPI. (The indigenous leaders of the TTPI eventually chose to establish four separate polities, including one US commonwealth and three freely associated states.)

Guåhan and the TTPI also benefited from the lifting of the security clearance that had been initiated prior to WWII, ostensibly to strengthen the security of US bases. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had designated Guåhan a Naval Defensive Sea Area and Guam Island Airspace Reservation in 1941, but nearly 20 years after the war ended, entrance to Guåhan and the TTPI, remained restricted by the Naval government, which required permits to control who could enter the island. With pressure from the UN Trusteeship Council, which toured the TTPI every three years to critique the level of progress in social, economic, and political development (and to which the US reported annually), President John F. Kennedy (1961-1963) quickly set several changes in motion to address UN criticisms and accelerate the TTPI’s progress toward the goals set out in the Trusteeship agreement.

Additionally, by 1961, the US was one of the few remaining trusteeship (colonial) powers, a circumstance which drew heavy international criticism. Kennedy pushed for greatly increasing funding for the TTPI and shut down CIA operations in Saipan to negate the UN’s criticism of the islands being partly under military rule. Kennedy then resolved the UN’s criticism concerning the TTPI headquarters by moving the headquarters from Guåhan to the vacated CIA buildings on Saipan. Kennedy also lifted the security restrictions for the TTPI which had stifled economic and political development. At the same time, he lifted the security restrictions for Guåhan. Had international pressure not been placed on the US regarding the TTPI, it is unknown when the security restrictions for Guåhan would have been lifted, which would have changed the trajectory and history of economic development for the island.

Similarities and differences between Guåhan and the TTPI

The creation and operation of the TTPI was no small task. It involved the establishment of an entire civil government, composed of hundreds of staff, whose work was assisted in some ways by nearly 1,000 Peace Corps volunteers at one point. It was responsible for administering numerous culturally, linguistically, and historically distinct peoples, who inhabited a vast expanse, and assisting their social, economic, and political development. Much of this effort was guided by the US goal of having TTPI areas enter permanent relationships with Washington so that its strategic interests in the region would continue to be met, and demonstrating to the world the success of US democracy.

On the one hand, US strategic interests continue to be served as Guåhan and the former TTPI islands remain both a network of defense for the US as well as bases to project power as necessary to East and South Asia. Indeed, whether as a US commonwealth or sovereign nation in free association, each former TTPI area has an ongoing relationship with the US today, allowing US military access and providing financial and developmental support through direct, multi-year US funding and a myriad of federal health, education and transportation programs. On the other hand, many critics would say that the US has fallen far short of its democratic ideals and goals in its relations with the TTPI and Guåhan. Though both Guåhan and the TTPI progressed socially and economically during the trusteeship years, self-determination was achieved only by those islands under the oversight of the UN trusteeship system. Other US territories which lacked the same amount of UN scrutiny and accountability, remain on the UN’s list of non-self governing areas entitled to self-determination, nearly three decades after the last of the TTPI islands gained independence.

Table 1

Table 1. Presidents during the US Administration of the TTPI

| President | Years in Office |

|---|---|

| [Franklin D. Roosevelt]* | [1933-1945] |

| Harry S. Truman | 1945-1953 |

| Dwight D. Eisenhower | 1953-1961 |

| John F. Kennedy | 1961-1963 |

| Lyndon B. Johnson | 1963-1969 |

| Richard Nixon | 1969-1974 |

| Gerald Ford | 1974-1977 |

| Jimmy Carter | 1977-1981 |

| Ronald Reagan | 1981-1989 |

| George H.W. Bush | 1989-1993 |

| Bill Clinton | 1993-1994 |

Table 2

Table 2. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands Headquarter Location and Administrator

| Location | Years of Existence | Type of Administration | High Commissioners |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Pre-TTPI operations were directed largely from Guåhan] | [1944-1947] | [Wartime Military Government] | – Vice Admiral John H. Hoover, Military Governor, 1944 – Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Military Governor, 1944-1945 – Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Military Governor and CINCPACFLT,* 1945-1946 – John H. Towers, Military Governor and CINCPACFLT,* 1946-1947 |

| Guåhan | 1947-1949 | US Naval Government | – Admiral Louis Denfeld, US Navy and CINCPACFLT,* 1947-1948 – Admiral DeWitt Clinton Ramsey, US Navy and CINCPAFLT,* 1948-1949 |

| Hawai’i, with Field Headquarters in Guåhan | 1949-1951 | US Naval Government | – Admiral DeWitt Clinton Ramsey, US Navy and CINCPAFLT,* 1948-1949 – Admiral Arthur W. Radford, US Navy and CINCPACFLT,* 1949-1951 |

| 1951-1954 | Civil Government, under the Department of Interior | – Elbert D. Thomas, 1951-1953 – Frank E. Midkiff, 1953-1954 – Delmas H. Nucker, 1954-1961 |

|

| [Control of Saipan and Tinian are returned to the Department of the Navy based in Guåhan] | [1953-1962] | [US Naval Government] | – Elbert D. Thomas, 1951-1953 – Frank E. Midkiff, 1953-1954 – Delmas H. Nucker, 1954-1961 – Maurice W. Goding, 1961-1966 |

| [Control of the islands north of Saipan are returned to the Department of the Navy based in Guåhan]** | [1953-1962] | [US Naval Government] | – Elbert D. Thomas, 1951-1953 – Frank E. Midkiff, 1953-1954 – Delmas H. Nucker, 1954-1961 – Maurice W. Goding, 1961-1966 |

| Guåhan | 1954-1962 | Civil Government under the Department of Interior | – Frank E. Midkiff, 1953-1954 – Delmas H. Nucker, 1954-1961 – Maurice W. Goding, 1961-1966 |

| Saipan | 1962-1990*** | Civil Government and later, Office of Transition, both under the Department of Interior | – Maurice W. Goding, 1961-1966 – William R. Norwood, 1966-1969 – Edward E. Johnston, 1969-1976 – Peter Tali Coleman (acting), 1976-1977 – Adrian P. Winkel, 1977-1981 – Daniel High (acting), 1981 – Janet J. McCoy, 1981-1987 – [Charles D. Jordan, Director of Office of Transition, 1986-1991] |

| Washington D.C. | [1990 or 1991?] to 1994 | [Office of Territorial and International Affairs, a unit of the Dept. of the Interior] |

**This left the Rota as the lone island in the Mariana Island archipelago within the TTPI to be under the civil government of the Department of the Interior from 1953-1962. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy returned all northern Mariana islands to the civil government of the Department of Interior.

***The United Nations officially dissolved the Trust Territory in 1990.

For further reading

“Editorial: The Pacific Islands.” Life Magazine 23, no. 6 (1947): 30.

Farrell, Don A. History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Public School System, 1991.

Kit Porter Van Meter Marianas Collection. “Micro 5 Peace Corps Training on Udot.”

Leon Guerrero, Edward. “The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) Explained | Micronesian Modern Political History.” PulanSpeaks. Streamed live on 19 April 2021. YouTube video, 6:55.

Maga, Timothy P. “Rust Removal: the New Frontier in Guam and the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.” In John F. Kennedy and the New Pacific Community, 1961-63. Houndmills: MacMillan Press, 1990.

Meller, Norman. “The Congress of Micronesia A Unifying and Modernizing Force.” Micronesica 8, no. 1-2 (December 1972): 13-22.

Northern Marianas Humanities Council. “From the White House.” DIGITAL ARCHIVE.

––– “Dwight D. Eisenhower.” From the White House.

––– “Lyndon B. Johnson.” From the White House.

––– “John J. Kennedy.” From the White House.

––– “Richard Nixon.” From the White House.

Richard, Dorothy E. United States Naval Administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. Vol. 3. Washington, DC: OPNAV, 1957.

Stanford University School of Naval Administration. Handbook on the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands: A Handbook for Use in Training and Administration. Washington, DC: OPNAV, 1948.

––– Handbook on the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands: A Handbook for Use in Training and Administration. Washington, DC: OPNAV, 1949.

Thomas, R. Murray. “The US Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (Micronesia).” In Schooling in the Pacific Islands: Colonies in Transition. Edited by R. Murray Thomas and T. Neville Postlethwaite. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2016.

Topping, Donald. “Review of U. S. Language Policy in the TTPI.” In History of the U. S. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands: Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Pacific Islands Conference. Edited by Karen Knudsen. Honolulu: Pacific Islands Studies Program, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1985.

United Nations. “Trusteeship Council. Official Records. Supplement Visiting Mission.” United Nations Digital Library.

––– “United Nations Charter (full text).”

United Nations Security Council (2nd Year: 1947). “Resolution 21 (1947).” United Nations Digital Library, 1964.

US Department of Interior Office of Territories. Report on the Administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands by the United States to the United Nations, 1951-1952. Washington, DC: GPO, 1953.

––– Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, 1953-1957. Department of State Publication 5735, 6243, 6457, and 6607. International Organization and Conference Series 3: 103, 111, 120, and 126. Washington, DC: OPNAV/DoS, 1955-58.

––– Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, 1957-1962. Department of State Publication 6798, 6945, 7183, and 7362. International Organization and Conference Series 2, 9, 18, and 30. Washington, DC: DoS, 1959-63.

––– Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, 1962-1966. Department of State Publication 7676 and 7811. International Organization and Conference Series 53 and 59. Washington, DC: DoS, 1964-67.

––– Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, 1966-1970. Department of State Publication 8379 and 8520. International Organization and Conference Series 80 and 91. Washington, DC: DoS, 1967-71.

US Navy Department. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, 1947-48. PONAV-P22-100E. Washington, DC: OPNAV, 1948.