Spanish begin visiting the Marianas sporadically

Between 1565 and 1665, Guam’s southwest coast received sporadic visits from Spanish vessels, including the first wreck of a trade galleon (San Pablo, 1568), as well as the first encounters with Dutch and English mariners. However, a more significant exchange venue was established in the 30-mile wide Rota Channel to trade with the Spanish ships crossing regularly from New Spain (Mexico) to the Philippines.

Trading on the southwest coast replicated the pattern set during Miguel Lopez de Legazpi’s visit but this anchorage did not meet the early requirements of Spain’s silver ships from Acapulco. The navigation route of the Spanish trade galleons was prescribed and westbound vessels were directed to avoid the coral-rimmed coasts of the Marianas, probably as a result of the San Pablo disaster. The 30-mile wide Rota Channel became the major arena of iron trade interaction during the 1570s.

Islanders learned to expect visitors around June

The Acapulco ships usually hove-to (slacken sails to slow movement) and drifted through the channel and several miles off Guam’s northwest coast. Islanders anticipated the galleon’s arrival, which usually occurred in June, as southwest monsoon winds began blowing across the Philippine Sea, signaling the annual transition to the islands’ rainy season. Some islanders prepared goods in advance and launched their canoes as soon as the ships came into view. They sailed out en masse, larger craft carrying up to a dozen islanders, including women.

Accounts note 150, 200 or 300 canoes, carrying as many as 1,000 islanders, sailing 10 to 15 miles offshore to meet the galleons, virtually covering the sea around these towering, multi-decked vessels, some of which were among the largest ships in the world at that time. Crewmen and passengers would line the deck rails or lean out of portholes and stern windows, ready to barter or just observe the encounter. Some islanders were cautious, remaining out of harm’s way, shouting “arrepeque! arrepeque!” (Don’t shoot!) and coming closer only when assured of peaceful exchange.

Others came directly alongside or anchored their canoes to cables that some captains ran off the stern to accommodate traders. Occasionally, islanders called out a greeting, which different observers transcribed in several ways, such as “Chamarri, Her, Her,” or “Chamori, Hierro, Hierro” or “Charume, heoreque!”

These islanders reportedly rubbed the palm of their hand along the side of their heart or repeatedly drew their hand across their chests, while repeating these words. They were likely identifying themselves as members of the ruling elite, using customary body language and the indigenous term for their elevated status (chamorri); while indicating they wanted to trade for iron, using the Spanish hierro.

Most islanders did not board the galleons, using ropes and cords to exchange goods. Occasionally, some islanders boarded the galleons when repatriating clerical sojourners or castaways, recognizing former castaways or tempted by a prospect of gaining more iron or acquiring a sword or arquebus. Galleon officers were generally wary of allowing islanders on board because of incidents in which some had snatched weapons from unsuspecting crewmen. The trade went on day and night in all weather conditions, causing some islanders to become hoarse, with sore throats and colds and exhausted from exposure and physical exertion.

Food, mats, rope, boxes offered for trade

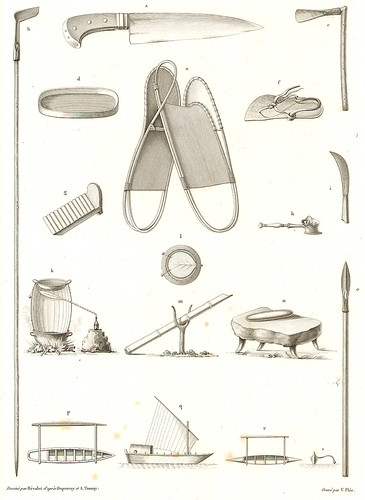

In addition to food staples, islanders also offered finely-woven mats and baskets, coils of coir sennit, dove-like birds in wooden cages and small turtle-shell boxes. Some accounts mention “hens” or “fowls” which could have been edible land or seabirds, such as those islanders harvested from the Uracas (Farallon de Pajaros) rookery. A few accounts, circa 1630s, mention “chickens” which could have been the offspring of Gallus gallus brought to the islands by trade or shipwrecks. After the loss of the Santa Margarita (Rota, 1601) and Concepción (Saipan, 1638), some islanders offered gold neck chains and ivory carvings salvaged from the wrecks, leading observers to marvel that the islanders valued iron more than gold.

The matao traded for nails, knives, hatchets, scissors, and cask hoop iron. Islanders also recovered a spectrum of these goods, including cutlasses and machetes, as salvage from the Santa Margarita and Concepción wrecks. The Spanish occasionally traded machetes and cutlasses but did not offer swords, though some accounts note the islanders’ desire to acquire these. Arquebuses (early guns) were not traded.

Trade tactics emerged

Sometimes islanders would take the iron of several European traders but only compensate a few. Occasionally, food baskets were filled with sand and rocks and the coconut oil would be a thin layer floating on seawater, as had occurred in Legazpi’s visit.

Some crewmen and passengers were so angered by these practices that bartering sessions occasionally ended when irate traders fired arquebuses at the islanders who returned fire with sling stones or dived into the water for protection. Other visitors, however, saw the tricks as a tactic to win favorable terms of trade. A Legazpi chronicler noted:

Every day that the fleet was anchored there, there were [canoes] alongside to sell, but with such an art that each day they were selling dearer, doubling the prices, and on top of that, they were playing very pretty and even sad jokes with what they were selling.

Visitors who experienced a difficult crossing were at a disadvantage when they arrived at the Marianas, as a Legazpi officer noted:

All of this was tolerated on account of the necessity that the fleet had of all the things they brought ….

Despite these tactics, some Europeans felt they were getting a bargain. A 1632 trader who had bartered a section of barrel hoop for:

a couple of chickens” observed, “[T]hey [were] thinking that they were fooling us, [but] they were those who were being fooled, given the large quantity they would give in exchange for a few trifles of iron.

The exchange tactics that angered galleon traders were not characteristic of the islanders’ normal social behavior, however. Accounts of clerics and ships’ officers who lived among them testify that the matao were generous in gifting, customary exchanges and sharing community resources. Theft was considered reprehensible conduct and socially censured. But the transactional ethos underlying indigenous exchange protocols, including customary obligations and social indebtedness, was not necessarily operative when islanders were dealing with transient foreigners.

Because they were interacting beyond their spheres of prescribed behavior for kin-group, fellow villagers and neighboring islanders, some island traders sought to maximize benefit at the expense of strangers by using haggling, whatever the market will bear, caveat emptor and seizure by stealth. The absence of social censure governing this new category of galleon exchanges led to behaviors that were the product of this new sphere of contact with visitors. They were not a typical indigenous exchange practice.

Care given to stranded mariners and clergy

The care and return of clerical sojourners and shipwreck survivors provided the islanders an additional means of acquiring iron, which led to more intensive cross-cultural interaction as well as generated positive images of the matao among Spanish officials. Beginning with the beachcomber Gonzalo de Vigo, a cabin boy from Ferdinand Magellan‘s Trinidad, and then the wreck of the San Pablo in 1568, the islanders had learned that helping stranded Spanish mariners could reap rewards of iron and other goods from grateful Spanish castaways and the ships repatriating them.

These developments are reflected in the accounts of clerical sojourners Fray Antonio de los Ángeles and Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora. The former arrived on the Acapulco ship Santo Thomas in 1596 and jumped into an islander’s canoe during a trading session. Joined by a Flemish soldier and Spanish sailor, de los Ángeles stayed for several months with a matao family in northern Guam. The cleric reported that they were well treated, noting that because the islanders placed such a high value on iron:

the natives are eager to welcome the Spaniards who pass that way. Knowing that each year they will make port, they will prepare presents of vegetables because they want very much to trade and although they have no dealings with them, they hold a great affection for them.

He described the islanders as loving and industrious people who showed great respect to their elders. Though they were called ladrones (Spanish for “thieves”), he noted, “they consider it evil to steal.” Despite their easygoing nature and hospitality, de los Ángeles “had not found a single fruit of his desire” [converts] during his sojourn. His treatment, however, favorably impressed Spanish officials, prompting the governor of the Philippines to report that the cleric’s island hosts were “tractable and kindly people [who] regaled him and his companion[s] and showed them much respect.”

Hosting clerics or shipwreck survivors had a prestige value for the matao, Pobre noted when describing how Santa Margarita castaways were treated. High status households on Rota “consider it a great honor to have a Spaniard in their home; also because they can expect to receive a substantial ransom in iron for one of them,” the cleric wrote. “They hold Spaniards who are …. well behaved in high regard.” Santa Margarita survivors confirmed Pobre’s view, reporting that “[t]he Indians of that island make a fuss over and entertain the Spaniards …without having them do work.”

There were an estimated 49 to 50 survivors of the Santa Margarita and 30 to 40 from the Concepción, who were distributed among several villages to high-ranking families, sharing the burden of housing, food and care as well as return of the castaway rewards among the leading kin-groups. Pobre’s host was a village leader named Sunama, from Rota’s northwestern coast, who was trading with the 1602 galleon when the cleric enticed him near with the gift of a large iron knife. Another cleric, Fray Pedro de Talavera, joined them in Sunama’s canoe. The chief and his wife, Sosanbra, regarded the clerics as sons, showed concern for their welfare and treated them kindly.

Though about 25 Santa Margarita castaways were repatriated by the galleon that brought Pobre, more than 20 remained, including 18 slaves who refused an offer to be returned to the Philippines, choosing to remain in the islands. When the galleon Jesus Maria arrived off Rota in October 1602, islanders alerted Pobre and Sunama transported the cleric to the vessel, where the entourage was warmly received and amply rewarded.

Sunama reportedly received knives, scissors, and several iron hoops as well as a monkey. Galleon officials reported the return of the castaways was accompanied by “joy, great friendship and goodwill” and the parting with “weeping and great sorrow.” Two other religious men and a Spanish soldier remained in the islands along with other Santa Margarita castaways. The clerics and soldier were safely repatriated several months later on the next Acapulco ship.

Some islanders who had hosted castaways looked for them during subsequent trading sessions with the galleons, perhaps reflecting an expectation of social indebtedness from those they had helped. Nearly a decade after the Santa Margarita wreck, for example, a “robust youth” from Rota came to look for a man who had lived with his family.

“As soon as the [islander] saw him, he boarded our vessel fearlessly,” an officer reported. “And still with no signs of fear he went among our men and threw himself into the arms of the man whom he knew, and who had eaten his bread and lived in his house.” The crewman “knew something of their language and customs because of his stay among them” and helped to make sure the youth was “loaded down with scissors, knives and iron.”

Not all castaways warranted generous treatment, however. About a dozen Santa Margarita officers and crewmen were killed, Pobre was told, because “their savage threats had led [the islanders] to believe they had come to seize their land.”The cleric also heard that four other wreck survivors living on Guam were killed because they had repeatedly struck the children of matao and done other terrible things. In addition, due to their dire physical condition, several severely debilitated passengers on the ill-fated vessel were dragged ashore and killed when the wreck was abandoned.

Islanders on Saipan reportedly killed several officers and crewmen from the Concepción, but a number of the castaways made their way to other islands where they were well-treated and distributed among families. Six “persons of account” among these survivors sought immediate repatriation, leading some chamorri to make special efforts to return them to Manila.

Taga, a principal chief (maga’ låhi) of Tinian, reportedly assisted a number of these castaways, protecting them and arranging for their transport to Guam, where Kepuha, the maga’ låhi of Hagåtña, arranged for the repatriation passage of six “persons of account” in two ocean-going canoes manned by islanders. The group crossed the Philippine Sea in about two weeks, reaching Samar on 24 July 1639.

The islanders told officials “that the Spanish are good men, and leave us iron when they pass there.” Manila authorities reported that:

[t]he Indians of Uan [Guam] sent those Spaniards so that they could give the news and send a boat for the other 22 Spaniards who are alive there, with some Indians and negroes, and carry them iron.

Another special repatriation effort in 1640 returned additional Concepción survivors, including the ship’s pilot, Esteban Ramos, in a modified island canoe that made the crossing in 18 days. Ramos later became a galleon captain and made an official declaration in 1665, supporting a mission for the Marianas. He described the islanders as “a docile and affable people” and asserted the mission could be carried out for very little cost. “No other escort will be needed nor garrison, for these people are most peaceful and of good disposition.”

Other Concepción castaways were repatriated to passing ships over the next two decades, including four Tagalog-speaking men as late as 1664. Several other castaways chose to remain in the islands. A few of these beachcombers became cultural informants and interpreters for the 1668 Jesuit mission, including Pedro Jiménez and Francisco Maunahan, from the Philippines; and Lorenzo de Morales, a native of India’s Malabar Coast.

The Matao Iron Trade entries

- Part 1: Contact and Commerce

- Part 2: Galleon Trading and Repatriation

- Part 3: Appropriation and Entanglement

For further reading

Campbell, I.C. “The Culture of Culture Contact: Refractions from Polynesia.” Journal of World History 14, no. 1 (March 2003): 63-86.

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Diaz, Vincent M. “Simply Chamorro: Telling Tales of Demise and Survival in Guam.” The Contemporary Pacific 6, no. 1 (1994): 29-58.

–––. Repositioning the Missionary: Rewriting the Histories of Colonialism, Native Catholicism, and Indigeneity in Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2010.

Driver, Marjorie G. “The Account of a Discalced Friar’s Stay in the Islands of the Ladrones.” Guam Recorder 7, no. 1 (1977): 19-21.

–––. “Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora and His Account of the Mariana Islands.” The Journal of Pacific History 18, no. 3 (1983): 198-216.

–––. “Cross, Sword, and Silver: The Nascent Spanish Colony in the Mariana Islands.” Pacific Studies 11, no. 3 (1988): 21-51.

–––. “Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora: Hitherto Unpublished Accounts of His Residence in the Mariana Islands.” The Journal of Pacific History 23, no. 1 (1988): 86-94.

García, Francisco. The Life and Martyrdom of Diego Luis de San Vitores, S.J . Translated by Margaret M. Higgins, Felicia Plaza, and Juan M.H. Ledesma. Edited by James A. McDonough. MARC Monograph Series 3. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 2004.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. “From Conversion to Conquest: The Early Spanish Mission in the Marianas.” The Journal of Pacific History 17, no. 3 (1982): 115-37.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ, and Marjorie G. Driver. “From Conquest to Colonisation: Spain in the Mariana Islands 1690-1740.” The Journal of Pacific History 23, no. 2 (1988): 137-55.

Lévesque, Rodrigue. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vols. 1-5. Québec: Lévesque Publications, 1992-1995.

Quimby, Frank. “The Hierro Commerce: Culture Contact, Appropriation and Colonial Entanglement in the Marianas, 1521-1668.” The Journal of Pacific History 46, no. 1 (2011): 1-26.

Thomas, Nicholas. Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.