The Hopkins Report

Table of Contents

Share This

Navy set up Commission to report on US territories in 1947

In 1947 the United States Navy created the Hopkins Commission to review and make recommendations about the naval governments of Guam and American Samoa. There was much public criticism of the Navy’s rule over these island territories at the time. Navy officials hoped the resulting report would allay these concerns.

On the surface, the Hopkins report appears to be a straightforward accounting of what it was tasked to do. However, there is a deeper story to this report involving struggles for power and authority among federal government agencies and the continuation of a colonized people fighting to, at long last, have civil rights and self-rule after decades of being denied them within the self-professed ‘greatest democracy’ in the world.

A study of the who, what, where, when, and why of the Hopkins report indicates the document was a strategically played pawn in the Navy’s grand vision for post-World War II US national security, despite President Truman’s assurances that the US was “not fighting for conquest” and that “There is not one piece of territory or one thing of monetary nature that we want out of this war.”

Who: The Players

The Authors: On 8 January 1947, a three-man civilian group, referred to as the Hopkins Commission, was called together. The men were carefully selected, each holding ties to the military, relevant issues at hand, and/or the US Pacific territories.

- Ernest M. Hopkins headed the commission. He had been president of Dartmouth University (1916-1945). Though a graduate of the school, he did not fit the typical mold of a college president as he was not an academic. Instead, Hopkins spent the majority of his earlier career in the business world and, during World War I and II, he was named Assistant Secretary of War for Industrial Relations and later served in the Office of Production and Management.

- Maurice J. Tobin was a former governor of Massachusetts, known for his advocacy of fair employment practices and support of labor unions.

- Dr. Knowles A. Ryerson rounded out the commission. He was the Dean of the College of Agriculture of the University of California but had also worked with the military previously regarding US territories. According to at least one account, therein lies the rub. Ryerson, answering a call from Admiral Nimitz, authorized a report that recommended vast amounts of acreage in the Pacific be used for vegetable farming to boost soldier morale.

This recommendation resulted in the seizing of hundreds of acres from local farmers on Guåhan who were struggling to recover from the devastation and disruption of the war which had laid waste to much of the island. Coconut, papaya, and breadfruit tree groves on those lands, which made up a substantial amount of the local food supply, were destroyed. Thousands of other acres also were seized and the people of Guåhan were prohibited from gathering foodstuffs from these areas.

- James V. Forrestal was the Convener of the Commission. The US Navy commissioned the Hopkins report through Forrestal, a self-made man who knew how to make big things happen. A former naval aviator turned financier worth millions, Forrestal had been appointed Under Secretary of the Navy (1940-1944), Secretary of the Navy (1944-1947), and finally, in September of 1947, the US’s first Secretary of Defense (1947-1949). In these roles, he fought in wars, visited battlegrounds, and was described as a “tough-minded civilian warrior.”

- Other players included the Department of War (the Army, which then also included the predecessor to the Air Force), the Department of State, and the Department of the Interior (DOI), each of which played various roles in the commissioning and use of the Hopkins report.

- Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes (ick-ees), played an especially prominent role. A Chicago lawyer, he served as Secretary for nearly 13 years (1933-1946), and is noted as the second longest-serving Cabinet member in US history. He bore two nicknames, one given to him in recognition of his crusades against corruption – “Honest Harold”, the other was self-proclaimed – “curmudgeon”, meaning a cantankerous person who is not very tolerant of certain things. Ickes lived up to both of these nicknames, abruptly ending his lengthy administration of Interior in protest of President Truman’s nomination of an oil magnate as Undersecretary of the Navy despite Ickes public objections.

Ickes was a staunch supporter of civil rights and civil liberties, had brought civilian governments to the Philippines, was preparing to establish civilian governments in the Pacific territories, and was a straight talker. Ickes was president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Chicago and among his associates was the first African-American to hold a cabinet position in the US federal government. Ickes’ successor, Julius A. Krug, picked up the reins of some of the Interior’s issues with the Navy and likewise supported Interior control of civil administration for the Pacific territories.

- Several Washington, DC-based lobbying groups were committed to advocating civil rights and self-rule for the CHamorus of Guåhan, including the Institute of Ethnic Affairs (IOEA), the Institute of Pacific Relations, and the Friends of Guam. CHamoru political leaders had established the Friends of Guam, a group committed to instituting measures that would control the Navy’s ability to dictate essentially every nuance of life for Guåhan CHamorus, as had been the case for over 40 years. Moreover, authoritarian Navy control had continued even after CHamorus and others around the world had fought a war on behalf of democracy. These support organizations had a wide range of local, national, and international members, several of whom were quite influential, including the IOEA, whose Honorary Vice President was former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, known for her progressive stances.

- The people of Guåhan: Island civic leaders such as Baltazar J. ‘BJ’ Bordallo, Francisco B. ‘FB’ Leon Guerrero, Carlos P. Taitano, Antonio Won Pat, Simon Sanchez, Agueda I. Johnston, and Concepcion ‘Connie’ Barrett had key roles in the political struggle that eventually clinched the attainment of certain civil rights and self-rule for the peoples of Guåhan. While leaders such as these are often recognized, the consistent support by fellow leaders and the people of Guåhan were crucial components of their successes.

Where: The difference geography can make

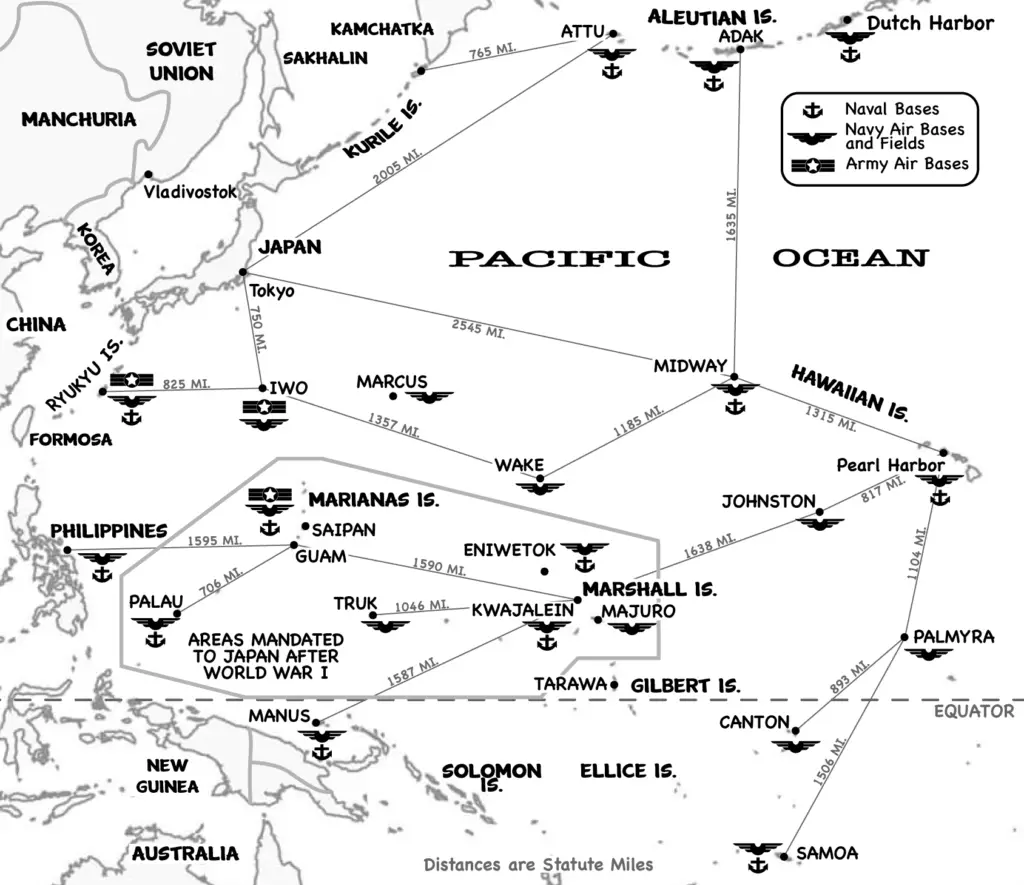

The US values Guåhan because of its geographic location which is strategically beneficial for national interests. In fact, it is the single reason that the US annexed Guåhan as a spoil of war from the Spanish-American war of 1898. Having an island near East Asia to serve as a coaling station to fuel naval steamships crossing the Pacific was considered to be in the national interest at the time. The surrounding Micronesian islands also had been colonized by the Spanish and thus could have been annexed by the US had it been disposed to retain them. However, it was not until decades later, after Guåhan and Hawai’i had been attacked in World War II (WWII), that the US reevaluated Micronesia’s strategic benefit as part of the US’s outer ring of defense.

After WWII, Forrestal himself wrote in a letter to the New York Times:

Our national security is important…therefore, we must maintain strong Pacific bases. Single island positions cannot be considered strong bases. Selected islands can, however, together with Guam, form a far-reaching, mutually supporting base network, although each alone would fall far short of being an impregnable bastion. Large-scale offensives cannot be mounted from a small island base. An appropriate base network, however, permits full exploitation of mobility of forces which was such a vital factor in victory in the Pacific. (emphasis added)

In that letter, Forrestal also referenced statements by former US President Herbert Hoover that, “it was his hope that we were going to hold the Pacific islands as primary to the safety of the American people,” to which Forrestal heartily concurred. In fact, shortly after WWII officially ended, in February 1946, the New York Times published a sizable map and article which disclosed that the Army and Navy were constructing numerous anchorages and airfields across the Pacific that were deemed too necessary to wait for the war’s final political settlements. These grand plans very specifically included bases on Tinian, Saipan, and Guåhan in the Mariana Islands; the Ryuku Islands (Okinawa); the Marshalls; the Iwo Islands; Ulithi, Chuuk and three islands in Palau—Peleliu, Angaur, and Babeldaub.

Also owing to the location of Guåhan and other islands in Micronesia, they were initially discovered and settled by peoples originating out of Island Southeast Asia who became the Indigenous peoples of those islands. Unfortunately, the US treatment of Indigenous people has always been problematic. It has been fraught with discrimination, racism, and inhumane treatment. Continental territorial expansion occurred largely by ignoring Indigenous First Nations peoples’ inherent rights and claiming their land. This lack of recognizing Indigenous rights continued in many ways when the US began to claim ownership of islands beyond the nation’s continental shores. Guåhan CHamorus were labeled by some in the US as ‘brownies’ who differed enough to be denied citizenship status, civil and political rights, self-government and rule by law, rather than by Navy fiat.

When: Timing is everything

The years leading up to 1947 when the Hopkins report was commissioned had been pivotal ones. The US’s involvement in WWII had caused it to rise from a ‘midlevel’ global power to being the world leader. The US’s strategic policy aimed to defeat the enemy far from the continental US. In fact, possessions such as Guåhan are often referred to as ‘outposts.’ This policy, Japan’s multi-prong attack on US Pacific territories, and concerns about the political designs of nations in Eurasia propelled Guåhan and its surrounding Micronesian islands into new prominence in US naval strategy.

Controlling Micronesia would add another 3 million square miles of the Pacific, an area nearly the size of the continental US, to the nation’s outer lines of defense. The Navy was determined to build up a defense that would assure that the US would never again lose in the Pacific.

While the Navy was developing grand designs to increase its capabilities and holdings in the Pacific, the branches within the US military were challenging each other for prominence. Additionally, the Departments of War, State, Interior, and Navy were competing for control of the islands. Intermingled with these challenges, Guåhan CHamorus continued their struggle for civil rights and an end to naval rule. Though they had fought and died in the world war for ‘democracy’, had suffered a brutal WWII enemy occupation that US citizens living in states were spared, and had helped liberate the island, the post-WWII indigenous people of Guåhan experienced a disappointing continuance of their lack of any civil rights or self-rule as they were placed back under a naval government. Additionally, CHamorus were being displaced from their family lands and homes as the military took entire villages and thousands of acres of other land which were either bulldozed and developed into airfields and bases or left dormant. All of the lands appropriated by the Navy were transformed into restricted areas prohibited to the original landowners.

While CHamorus had consistently petitioned for civil rights and self-rule since 1901, their efforts were bolstered in 1946 by a public relations and media campaign conducted by supporters connected to the Institute of Ethnic Affairs, including Harold L. Ickes who kicked off the campaign in August of that year with a blistering speech on the failures and shortcomings of the naval government of Guåhan, a transcript of which was made readily available on island and elsewhere. Ickes speech was quickly followed up with a nationally published article entitled, “The Navy at its Worst”. A steady onslaught of press releases, statements by supportive members of Congress, and letters to newspapers such as the New York Times, and more heavily criticized the naval government of Guåhan and American Samoa as well as the Navy’s wartime government of the Micronesian islands that had been part of the Japanese mandate prior to WWII (the northern Mariana islands, Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, Kosrae, and the Marshall Islands).

Further, in 1947, anthropologist Laura Thompson, a founding member of IOEA, re-released her book, Guam and Its People, with new criticisms of the naval administration, copies of which were provided to members of Congress. At the international level, John Collier, President of the Institute of Ethnic Affairs, developed a UN resolution on non-self governing peoples, and along with Ickes and others, pushed for the United Nations to develop a trusteeship council and for the US to place the Japanese mandate islands into the UN’s trusteeship system, and out of the Navy’s hands. Some of this lobbying activity resulted in multiple bills for citizenship, civil rights, and self-rule for Guåhan.

Why: The reasoning behind the Hopkins Report

Attempting to maintain their administration of the Pacific territories, including the islands in Micronesia previously part of Japan’s mandate, the Navy carried out various offensive and defensive strategic actions to combat the inter-service and inter-departmental struggles for control. The Navy also sought to counter the deluge of criticisms published in newspapers across the nation by Harold L. Ickes and numerous other individuals and groups of various backgrounds and public acclaim. Navy strategies included their own public relations campaign to highlight naval ‘achievements’ in the islands; organizing a tour of the Pacific islands under Navy control by select newspaper correspondents; developing a School of Naval Administration at Stanford University to train naval officers for naval, military, and civil government; testifying in Congress and lobbying both Congress and the President to prioritize national security concerns in the Pacific; and if the islands were to be under a UN trusteeship, urging that it be a strategic trusteeship that allowed for military control and considerations.

Not the least of these strategies was the commissioning of the Hopkins report which gave the appearance of proactivity and tools with which the navy could vie for continuing its administration of the Pacific island territories.

In a rebuttal letter to Ickes published in the New York Times in September 1946, Forrestal made a case for continued and expanded naval administration. He called the former Secretary of the Interior’s criticisms of naval governance in the Pacific islands “irresponsible,” citing former President Hoover who stated, contrary to resolutions, statements, and testimony by the people of Guåhan, that:

The Navy has for many years administered such Pacific islands as we have held and I can say unqualifiedly that their administration has been completely without blemish.

Forrestal further pointed out that Hoover:

…continued to say that it would be a fatal mistake to remove these islands from naval administration” and that “such a holding could not be held an extension of imperialism because we have no designs for economic exploitation.

The Navy further rebutted criticisms, including those that resulted from the Hopkins report and resolutions by the Guam Congress, by releasing statements to the effect that they were doing everything they could and that they believed CHamorus could obtain their civil, political and economic aspirations through the Navy.

For much of 1947, the Navy fostered opinion articles in newspapers across the nation boldly entitled:

- Guam Natives Like Administration of Navy

- Natives of Guam Hope Navy to Stay on Island

- Naval Civil Government Investigation Promised

- Navy is Drafting Bill to Get Home Rule for Guam

- Organic Act is being Drafted by Navy for Congress

- Navy Pushes Home Rule and Act Granting Citizenship

- Legislative Power to Guam Natives is being Prepared by Navy

They also attempted to negate criticisms, such as those pointing to their lack of timely processing of CHamoru war reparations, by saying that many CHamorus did not want them and promoted statements such as that by a CHamoru “who lost everything he had” who had reportedly said, “I want no pay for what I lost.”

The Navy even went so far as to attempt to co-opt CHamoru loyalty to the US during the brutal wartime occupation in which they suffered starvation, beatings, and beheadings. Because CHamorus hoped to use this war-time patriotism to demonstrate that they had finally ‘earned’ civil rights and self-rule, the Navy attempted to rip this leverage away from them by claiming that the loyalty of CHamorus and others on Guåhan during the war was “the highest accolade to the quality of the navy administration.”

With great fanfare, the Navy submitted their own bill on civil rights and self-rule for the people of Guåhan accompanied by a joint statement issued by the Navy, Interior, State, and War Departments. The statement said that they favored a government of civilians for Guåhan, but agreed that the Navy would stay as administrator for an unspecified amount of time owing to the “strategic importance of Guam to our national security” as well as to the ongoing rehabilitation program on the island. Also, problematically, the bill the Navy submitted failed to use the term “civilian” and likewise left the Navy in control of Guåhan with nothing to compel the President or Congress to ever place the island under another department’s jurisdiction.

Other strategic Navy moves were applied locally. Governor Rear Admiral Charles A. Pownall was simultaneously the commander of the Mariana Islands and deputy military governor of the islands formerly part of the Japanese mandate. While he was issuing statements to the press that, “there is no question but that he holds the complete respect of the Guamanian people” and had asked the advisory Guam Congress “to speak out its desires” and to study and critique the Navy’s civil code, he also carried out various repressive actions.

He ordered the Office of Naval Intelligence to investigate CHamorus pushing for civil rights and self-rule. Pownell then released the purported investigation findings that claimed FB Leon Guerrero and others were communist subversives. He was said to have sent via the ‘coconet’ (the local informal word of mouth media) a veiled threat that Guam Congressman Carlos P. Taitano, a veteran Army officer and one of the leaders calling for civil rights and self-rule, could be called back to active military service. Pownall also withheld key information from Guåhan leaders – that the US would continue to provide support to the island even under civil government, information that would have eased their worries about calling for an end to the naval administration.

What: The report

The military government had, by the time of the Hopkins report, lasted nearly 50 years. That people of US Pacific territories still had not one guaranteed civil right nor any real level of self-government, and that a study such as this was needed to call for a modicum of democratic consideration for the people of Guåhan and American Samoa are testaments to the prevailing racial biases. While on one hand the report called for more consideration than CHamorus and Samoans had ever perhaps formally received, on the other hand racial and colonial biases are evident in the limited offerings of the report’s findings and recommendations. This might also be said of some of the thinking of even those fighting for civil rights and self-government for the peoples of the territories. Their view as to what was possible, in the 1940s, was largely limited to the confines of the US political-affiliation system. At the same time, these people helped provide an international “trusteeship” structure allowing for self-determination for non-self governing peoples.

The civilian commission appointed by US Navy Secretary James Forrestal was to study and make recommendations on the Naval administration of Guam and American Samoa with particular focus on the social, political, and economic status of the peoples of those islands. Prior to visiting the islands, the commission conferenced with staff of the School of Naval Administration at Stanford University including Dr. Keesing, a “well known authority on Pacific island matters,” with at least one member of the Department of State, and with Hawaii-based military officials and civilian scholars familiar with Guåhan and American Samoa, one of whom was Sir Peter Buck of the Bishop Museum a well-regarded expert on the peoples of Oceania.

The Hopkins commission visited Guåhan February 24 to March 9 and American Samoa March 9 to 16. While in the region, they also visited some of the former Japanese mandated islands that the Navy wanted to continue to administer and place bases. Perhaps interested in observing the Navy’s military government in the Japanese mandates, commission members also visited Saipan, Tinian, and Luta (Rota) as well as the islands of Koror, Peleliu, and Angaur in Palau.

For Guåhan, the Hopkins commission formally met with the military governors and members of the governor’s staff, held open public hearings (that did not include naval personnel), attended a session of the Guam Congress, and held interviews with a variety of people. The commission noted that at the open hearings, they had a translator available and invited people to speak in their Indigenous language.

The end-result of these investigations was an 80-page report submitted to the Secretary of the Navy. The report provides three main recommendations: to make the people of Guåhan and American Samoa US citizens, to have the “possessions” placed under organic acts, and to continue to have the Navy rule them for the immediate, although undefined, future. The commission also noted that the military needed to settle land and war claims and prioritize rehabilitation of the war-torn villages of Guåhan rather than building up military defenses. They briefly discussed education and economic considerations. The report’s appendices provided organic acts for Guåhan and American Samoa.

Limiting discussion to the report’s views on Guåhan, the following features of the Hopkins report are worth noting:

- Citizenship: The report first states that the people of Guåhan are entitled to full US citizenship which should be accomplished at the earliest possible date. It points out that other US territories, such as Puerto Rico, which was likewise attained in 1898 as a spoil of the Spanish-American war, had attained US citizenship decades earlier.

- Organic Act: The commissioners point out, again, that other territories had long had organic acts with ‘bills of rights.’ The commissioners also referred to the United Nations Charter noting the sacred trust that nations held regarding non-self-governing territories and their responsibilities for the peoples’ well-being, to respect for their culture, and to develop self-government. The commissioners supported expanding certain local abilities. For example, they recommended that the legislature have authority to approve all laws, the right for Guåhan’s people to appeal cases beyond the naval administrative system, that Guåhan’s people be assured two members in a court of appeals, and that a new post be created, that of a Secretary of Guamanian Affairs.

At the same time, they also recommended keeping heavy oversight of the local government – a US President-appointed governor who would then appoint nearly all the heads of the departments and subordinate executive officials, the judge of the island’s high court be appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the US Senate, and that local legislative vetoes be approved by the US President.

- Continued Navy Governance: While noting issues with current Naval administration, the commissioners also felt that those within the Navy were “devotedly conscientious” and “capable,” and further saw potential in the difference the School of Naval Administration at Stanford University could make. The commissioners also stated that the Navy was more equipped to provide the services needed than other federal government entities, and that the people of Guåhan essentially agreed with their assessments.

- Land Takings and War Claims: The report also tackled land takings and war claims. The committee called for paying rent for lands taken and stated that the military needed to determine how much land it needed for defense purposes, to take no more land, and to give back the rest. However, while they called out issues related to the complexity of processes regarding land takings, they didn’t remove it from navy control but instead recommended that the Secretary of the Navy appoint a stateside judge to oversee a special land court. Regarding war claims, they recommended immediate steps occur to speed up the process and the removal of “unsound and unfair” distinctions in the allowance of claims.

- Rehabilitation: The commission stated that the people’s needs, the rebuilding of their homes and villages, should be prioritized as well as kept as affordable as possible through navy assistance.

The report also had other recommendations many would find interesting today. It proposed: That the Marianas Islands be administered altogether as a singular unit. That, with the military occupying such a large percentage of the island, the federal government should contribute a proportion of the cost of island government. That the island should keep federal taxes as revenues. That federal aid and payment for work should be applied with more parity to the island and its people. While limited in envisioning how the economy would develop, it encouraged subsistence farming and fishing.

And notably, the report went a step further than other statements recognizing the sacrifices of Guåhan’s people during the WWII enemy occupation. It stated:

The Guamanian people rendered heroic service to the Nation in the recent war and displayed great courage, fortitude and loyalty. Such services, equivalent to service on the field of battle, should be recognized, both collectively and, in specific cases, individually.

That recommendation is a far cry from the war reparations process that unfolded and is still in many ways unresolved over 75 years later, long after all other such affected peoples in the US have been justly recognized for their sufferings through war reparations.

Individuals like Ickes, Collier, Thompson and many on Guåhan felt that the commissioners had been intentionally selected and artfully guided by the Navy so that the report whitewashed certain issues with the naval administration and twisted or ignored unfavorable statements about the naval government that some CHamorus had provided the commission.

The Hopkins report was but one strategic step among many. The different players continued carrying out publicity campaigns, passing resolutions, writing bills, providing Congressional testimony, lobbying Congressional Delegates and the President, and more as they vied for control over the people, the land, and the sea of Guåhan.

e-Publication: Hopkins Report

For further reading

Cogan, Doloris Coulter. We Fought the Navy and Won: Guam’s Quest for Democracy. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008.

Friedman, Hal M. “’Americanism’ and Strategic Security: The Pacific Basin, 1943-1947.” In American Diplomacy, 1997.

Guam Echo. “The Hopkins Report.” 15 May 1947.

Hopkins Committee. Hopkins Committee Report for the Secretary of the Civil Government of Guam and American Samoa. By Ernest M. Hopkins, Maurice J. Tobin, and Knowles A. Ryerson. Moffett Field: Naval Air Station, 1947.

Ickes, Harold L. “The Navy at its Worst.” Collier 118, no. 9 (1946): 22-23.

Institute of Ethnic Affairs. Newsletter. Limited numbers available at the RFT Micronesian Area Research Center, Unibetsedåt Guåhan, Mangilao, 1947-1952.

Maga, Timothy. “The Citizenship Movement in Guam, 1946-1950.” Pacific Historical Review 53, no. 1 (1984): 59-77.

Murphy, Shannon J. “Institute of Ethnic Affairs.” In Guampedia, last modified 8 June 2021.

National Park Service. “Harold Ickes.” Last modified 22 September 2020.

Quimby, Frank. “National Attention on Guam’s Postwar Campaign for Citizenship.” In Guampedia, last modified 2 March 2022.

Rogers, Robert. “Gibraltar of the American Lake 1945-1950.” In Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2011.

Thompson, Laura. “Guam: Study in Military Government.” Far Eastern Survey 13, no. 16 (1944): 149-154.

Utley, Robert M., and Barry Mackintosh. “Twentieth Century Headliners and Highlights.” In The Department of Everything Else: Highlights of Interior History. Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1989.

Wooley, Alexander. “The Fall of James Forrestal.” The Washington Post, 23 May 1999.