Seaweeds Overview

Table of Contents

Share This

Primary plant life

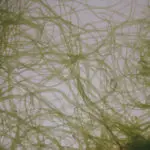

Seaweeds, or marine benthic algae, constitute the primary plant life in the marine waters around Guam. Seaweeds serve as the primary producers of nutrients made through the process of photosynthesis whereby carbon dioxide and water are converted to sugar and oxygen. There are 229 species of seaweeds reported from Guam waters. The species fall within four plant Divisions characterized by the dominant pigments and the chemistry of their stored food products – 22 species of filamentous Cyanophyta (filamentous cyanobacteria or blue-green algae), 70 species of Chlorophyta (green algae), 28 species of Phaeophyta (brown algae) and 109 species of Rhodophyta (red algae).

Seaweeds do not have the specialized vascular tissue found in higher plants that transport raw material and food throughout the body. The root-like structures are primarily attachment organs, i.e., holdfast. Seaweeds can take many forms, size and consistency, such as the filamentous brown Feldmannia, the blade-like red Halymenia and large calcareous green Udotea. Although the calcium carbonate rock-like alga Hydrolithon is normally not considered seaweed, it does belong to the Division Rhodophyta and is included in the total species counts of seaweeds for Guam.

Seaweeds manifest a variety of reproductive strategies, e.g., fragmentation, asexual reproduction via spores and sexual reproduction via sperm and egg cells.

Seaweeds are also the source of commercial “colloids,” gelatin-like products used as food preservatives, such as agar from Gracilaria and Gelidiella, and carrageenan from Hypnea and Eucheuma. The genus Eucheuma is extremely rare in Guam waters and the yield of agar from Guam’s Gracilaria is low. Gelidiella acerosa and Hypnea pannosa are small seaweeds, up to 6 cm high, and not abundant in Guam.

Only the green seaweed Caulerpa racemosa is harvested and eaten as a vegetable by Guam residents. A second seaweed, Gracilaria tsudae or chaguan tasi, has been avoided as of April 1991 when three individuals died by ingesting the seaweed.

Serve as shelter and food

Seaweeds serve as shelter and food for fish and invertebrates, and as substrata for smaller seaweeds (epiphytes) and invertebrates. In selected sectors of the lagoon environment and reef slopes, the major component of the sand can consist of the calcareous flakes of the green alga Halimeda. The crust-like or rock-like coralline algae are most dominant on the reef margin where the breaking high-energy surf occurs. The corallines also serve as cementing agents on loose coral substrata.

Many seaweeds have evolved secondary metabolites – natural chemicals that are not necessary for basic cellular and physiological life processes. The secondary metabolites in such seaweeds as Hormothamnium (blue-green alga) and Portieria (red alga) are noxious and serve as defense mechanisms against the numerous herbivorous fish and invertebrates that inhabit the waters around Guam.

For further reading

Lobban, Christopher S., and Roy T. Tsuda. “Revised Checklist of Benthic Marine Macroalgae and Seagrasses of Guam and Micronesia.” Micronesica 35, no. 36 (2003): 54-99.

Paul, Valerie J., ed. Ecological Roles of Marine Natural Products. Ithaca: Comstock Publishing Associates, Cornell University Press, 1992.

––––. “Marine Natural Products.” Marine and Coastal Biodiversity in the Tropical Island Pacific Region. Vol. 2, Population, Development, and Conservation Priorities, 311-23. Edited by LG Eldredge, JE Maragos, PL Holthus, and HF Takeuchi. Honolulu: East-West Center and Pacific Science Association, 1999.

Tsuda, Roy T. “Seasonal Aspects of the Guam Phaeophyta (Brown Algae).” In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Coral Reefs. Edited by AM Cameron, BM Cambell, AB Cribb, R. Endean, JS Jell, OA Jones, P. Mather, and FH Talbot. 43-48. Vol. 1. Brisbane: The Great Barrier Reef Committee, 1974.

Tsdua, Roy T., and Frieda O. Wray. “Bibliography of Marine Benthic Algae in Micronesia.” Micronesica 13, no. 1 (1977): 85-120.

Tsuda, Roy T., and Harry T. Kami. “Algal Succession on Artificial Reefs in a Marine Lagoon Environment in Guam.” Journal of Phycology: An International Journal of Algal Research 9, no. 3 (1973): 260-264.