A first hand account

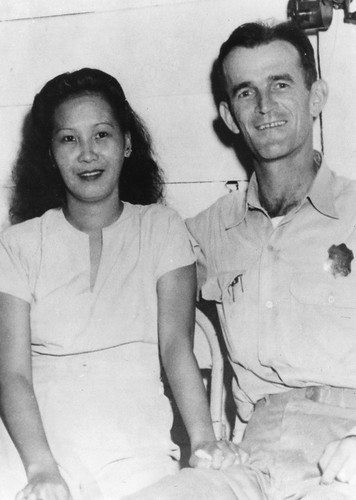

Robert O’Brien (1908 – 1988), born in New York, came to Guam in the 1930s with the US Navy. He married Marie Santos Inouye, a woman of CHamoru and Japanese descent, and they had four children, Patricia, Joseph, Henry and Robert. He participated in the short-lived defense of Guam and became a prisoner of war. O’Brien survived four years in a prisoner of war camp in Zentsuji, Japan.

Nearly 600 people were taken prisoner of war from Guam: 274 officers and men of the US Navy under Captain George McMillin, 153 officers and men of the US Marine Corps under Lt. Col William McNulty and 134 US civilians (nurses, priests, businessmen, etc.)

After returning home to his family on Guam, he and Maria had four more children, Catherine, Margaret, Dorothy and Ricarda. He lived a long life, despite his war experience.

In 1958, he finally responded to his brother Bill’s inquires about what had happened to him during the war. After some hesitation he wrote a detailed letter telling his war story. The letter was put away in an attic at his brother’s home in Michigan, only to be found recently after both men had passed away many years earlier.

Here is his letter to Bill:

USS Penguin on patrol

My gosh, Bill, I wish I could write you a concise but clear story of my 48 months plus a few days as POW. As you know, I have seldom mentioned much about that phase of my life. Matter of fact, I have never felt it was worth telling about. However, you have mentioned it several times and I have always ignored your queries. But after this last letter from you, I have decided to give you a brief outline. Many incidents have slipped my memory now. So it is only a sketchy story.

I did keep a diary during my POW days, and with some risk, as the Japanese were ruthless on anyone they even suspected of keeping a diary. Then, when the war ended and I had gone around and gathered my little scraps of paper hidden all over the place and put them together in a cardboard cover just before we left the prison camp, I some how lost the papers.

At the time I was so happy and excited over getting out of that hole that I didn’t feel the loss too badly. Since then I have often wished I had taken the time to find that diary. However, at times I have also felt it may have been just as well that I didn’t have the diary. There were some entries that might have caused me to harbor bitter feelings. As it is, today I think only of the humorous incidents about those days; and we did have many a funny incident, or at least now it seems that way. During the actual POW days, when we lived in uncertainty and were hungry all the time, it was quite different.

To give you just a few brief points, I will start from the beginning. On December 6, 1941 our ship, the USS Penguin, left Apra Harbor, Guam on a routine patrol, our main objective being to be on the lookout for Japanese subs. The situation was such at the time that we felt it wise to be on the lookout for snooping Japanese, though we really had not the slightest idea that a war was imminent. We didn’t even have our guns unlimbered or ammunition at hand, the ammo being still in the magazines down below. Ours was to be just a “routine patrol,” with orders only to observe and report what we saw. We spotted nothing, though for days we had been seeing high flying planes which we all presumed to be Japanese from Saipan, 120 miles away.

Then late in the evening of December 7, we started having boiler trouble with our Scotch boilers. We had knee action turbines on that rugged old World War I minesweeper built for one purpose only – to sweep mines from the North Sea after World War I. She had been converted and kept in service as a station vessel in Guam from 1929 until the War. Prior to that she had been a river gunboat on the Yangtze in China from 1921 to 1929.

Well, anyway after the boiler trouble started we obtained permission to return to the port for necessary repairs. We had a leaky header, which could not be fixed while under steam. Then of all times for such a thing to happen, our radio conked out, and when the radioman went to start the emergency radio, he found someone had made away with the carburetor. Anyway, we were without a radio. Of course we had not the slightest inkling a war was about to start and we already had permission to come in and repair our boiler; so we steamed into Apra Harbor the morning of December 8, 1941, just as chipper as could be.

Matter of fact, we had a big beach party planned for that same afternoon, our annual ship’s beach party. The day was also a big holiday for the whole island, being the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. As soon as we dropped the hook and got moored to our buoy in the harbor, even before the first boat from the beach had reached the ship, (we were about four miles out from the dock), we sent about one third of the crew ashore in our whaleboat, part of them heading for Recreation Beach to make initial preparations for our afternoon beach party, the rest on various assignments, the only pharmacist being among them, as he had some business at the hospital.

Our boat took a route in to the dock and missed a station boat (a little coal burning steamer from the old days when Dewey fought in Manila) steaming out to the ship under full power. They had a hand-carried message from the Governor telling the Captain that war had started early that morning with the bombing of Pearl Harbor (we are one day ahead of Pearl Harbor here because of the International Date Line) and ordering us to clear the harbor immediately and stand by for further orders. The beach had been frantically trying to radio us since early morning, but naturally they couldn’t reach us, as we had no means of communication. We were still without it and would be until the end, because our one and only radioman was in that first boatload of men already ashore. He had gone after spare parts.

Well you can imagine our consternation. There we were, moored to a buoy right in the middle of the harbor with our boilers dead, as we had doused them upon arrival as we could see the repair barge on the way out from the little Navy Yard in Piti. It would take an hour or so to get back up to full steam. However, we lit off and had enough steam in about ten minutes to start heaving in to the buoy and unshackling, and getting under way at reduced speed. We manned battle stations with our reduced crew, made all arrangements for battle, and while in the middle of unshackling from the buoy the first Japanese bombers came over.

We never got around to unshackling that chain. When we saw the bombers, I simply slipped the chain in the chain locker and let her rip. We commenced moving at the most agonizing pace possible, about 6 knots. The bombers missed us by about two miles in their first pass and went on to bomb shore installations, mostly fuel tanks and the Navy Yard. My heart was in my throat when they hit the Navy Yard, because our home was a short two blocks away from the yard gate and if their aim was anything like what it was when they bombed us, I feared for Maria and the four oldest who were just toddlers then.

Later, I learned I had no cause to worry because early that morning when word of the start of the war had reached Guam, the Governor had ordered Piti evacuated because of the yard being there. Maria and the children had already gone to Machanao, about twenty miles away in the north, near Yigo. Of course I didn’t know that until later.

Anyway, after unloading their bombs, the planes then came back at us with their machine guns. We had two 50 calibers on board with panoramic sights, but with tracers, very good for anti-aircraft. We chased them all off as they saw our tracers picking them up. We had a probable hit on one, but had no confirmation of downing it as it flew off toward Saipan losing altitude all the time. However, the last anyone saw, it was still airborne, so no downed plane was claimed.

Their few passes at us before they climbed out of range of the 50’s resulted in a few wounded, but no deaths. We managed to limp out of the harbor as ordered. At the moment, the skipper and I wondered what in h___ were we to do “standing by for further orders” with a crippled power plant, no radio, one third of the crew gone and very little store. The Philippines were the nearest place we could sail for and they were 1500 miles away; and at 6 or 7 knots, it would have taken weeks to get there; and we figured by then the Japanese would have the whole area under control. But orders were orders, so we patched up our few casualties the best we could without a medic, and patched the little damage we had from the strafing, and unlimbered our 3-inch 50 caliber guns which were suitable for anti-aircraft use, only we had nothing but panoramic sights intended for surface craft and submarines. Our only range finder was likewise for surface use. However, we did have some fused ammunition and when the bombers came back (apparently they had returned to Saipan for reloading) (they were two-engined float type planes, very old type, but extremely modern as far as Guam was concerned, as we didn’t even have a box kite there), we estimated their height and speed and let go.

Well, it went for an hour before the Japanese ever managed to drop bombs close enough to do any real damage. They had finally realized our erratic burst patterns around them meant we had no accurate means of drawing a bead on them; and then they went into pattern flying, making steady bombing runs and naturally sooner or later they had to connect. But, believe it or not, the bombs that undid us were not direct hits, and were from three planes and fell on both sides of us. However, they bracketed us close enough that they tore the ship apart with about a thousand or more holes. We lost power, the sick bay with the medicine was a shambles, 19 of us were cut up more or less, one man was killed, and there we sat like a ruptured duck just waiting for the next stick of bombs.

Luckily the Japanese had run out of bombs again and were off for more. While they were off we made a survey of the ship to determine how bad off we were. We found her settling fast, and with no means of getting back to part for the doubtful repairs we would need (the Navy Yard was geared for taking care of small craft and barges, and we had our overhaul work done annually in the Philippines), after an agonizing appraisal of what appeared obvious, the skipper said let her go and abandon ship. We were about one mile off shore and no boats. Our life rafts were in ribbons.

Though the ship was slowly sinking, we didn’t dare leave her afloat. There was the possibility she might float a day for all we knew, and the Japanese just might salvage her as they had a big outfit over at Saipan, so we pulled the plug on her to make sure the Japanese didn’t get her. She went down in about 2000 fathoms, for it gets awful deep awful suddenly off Guam. But just as we prepared to abandon ship, some Japanese planes came in again and this time they saved their bombs. They probably knew we were finished.

But the buzzards commenced strafing us again and we had our most seriously wounded already in the water in one patched-up raft and the body of the dead man with them. Since many of the crew was already swimming for the shore, it was a maddening thing to see the planes trying to pick them off and we were out of commission and couldn’t get back at them. I remained with the ship until the last, as I was not so bad off as the old man. He had half his left arm blown off and had lost a lot of blood. I swam that mile faster than Johnny Weismuller, but I can’t prove it because no one remembered to put a stopwatch on me at time. We were all pretty busy.

Anyway, I felt like it was my best mile ever, because those waters off Orote Point are full of sharks and barracuda. Of course, it never occurred to me at the time that those fish had taken off for safer spots after the first stick of bombs landed. Well anyway, we were a mess.

We managed to get an unwounded man through the boondocks to the Marine Station a few miles away, and through them we got trucks headed toward a selected rendezvous about a half-mile up from the rocky shore we landed on. It was really rough on bare feet going up through that carol and boondock growth. However, we managed it and within an hour or so we were all at the hospital and were patched up.

Defense of the Plaza

All who could make it then joined the few able-bodied men left at the Naval Station and a quick defense force was set up.

You see, Guam had no real defense force at the time. The 125 Marines here were primarily for internal security and training of the local police force. I was able to get out of the hospital right away, as most of my scratches were pieces of shrapnel, none of which had hit a vital spot. I still carry a few pieces around just as souvenirs.

I took over a half of the defense force. That is, I took over half as the NCO in charge, at the Plaza in Agana, as that was the selected spot for our last stand as we called it.

After we had organized our inadequate defense force, I obtained permission to find my family. I got to see Maria and the children out in Machanao late in the evening. They were all safe, but with only the clothes on their backs and enough food for several days. I spent the greater part of the night gathering their clothes up and getting more food to them.

The Japanese did not attempt to land until early on the third day. Them bombed and strafed us the first two days and nights. It was a bit annoying as we had only two Lewis machine guns, World War I vintage with pan feed, thirty round to the pan, and about 100 rifles stamped on the stocks, “Do not shoot.” They were given to Guam for use in training a militia and were actually dangerous to use. But we used them. I shared a 45 with seven other men. If I got it, number two took the gun; if he got it, number three took the gun and so on.

Well anyway, on the morning of the 10th, near 0100 in the morning, an outlying patrol sent word in that the Japanese were landing in several places. Soon a badly wounded civilian came in to verify this. I then went out on a short look-see myself and to this day I don’t know how I got back alive.

I went out about five miles to a beach we had been told the Japanese were landing at. I found no sign of them. They had (I learned later) landed and started toward Agana along the shore. Between the road and the shore there was a heavy growth of boondocks and trees; so I naturally didn’t see the Japanese. They saw me though and let me go and come. This I found out from one of our patrols that had been captured by the Japanese and was with them when I drove by. The Japanese kept our patrol from saying anything. I suppose their thought was that we were unaware they had landed and they decided to let one person come and go and thus felt that my report of not seeing them would cause us to be caught unawares in Agana.

However, we knew they were on the island, because of reports from others. And the wounded man who had escaped on the east coast about twelve miles from Agana. He had been driven in by another who had not been shot. Then our phone lines to several outposts were dead, which meant they had been cut.

Well anyway, we were waiting for them when they approached Agana, and they had to give themselves away for a group of our Penguin men, six in all, had been established at the power plant. The power plant was on the beach and when they saw the Japanese moving up on the beach, instead of falling back to the Plaza a half mile inland, as had been their orders, they decided to attack the Japanese. They did, and the initial surprise worked well for a few minutes. They had one BAR with them and they moved down a good number. However, the Japanese landed 12,000 troops (as I later learned) and this particular group must have numbered 2,000 according to the same patrol who had heard me pass on the road (he saved himself when our six commenced shooting, by falling to the ground), and in moments they recovered from their surprise and killed all six of our boys quickly.

The Japanese showed their later to be learned attitude by butchering these six so they were beyond recognition. Later one of the Fathers was permitted to take some CHamorus and bury them, and none could be identified, they were so badly mutilated.

Well, the Japanese knew we were aware of their presence by this skirmish, and as they entered Agana’s outskirts a die hard CHamoru who had defied orders and remained at his old home site, took a pot shot at the Japanese with a shotgun. The Japanese literally shot the house off the face of the earth. For a moment we in the Plaza had thought a pitched battle was going on between two Japanese units. They then burned the house site. The die hard, as well as what his intentions were, was never found out. He probably burned to ashes as the Japanese used flamethrowers.

By now we were ready as we could be and were deployed in the grass, behind bushes mind you, in the Plaza. A bush couldn’t stop a beer can, but we had nothing else, and for some reason nothing had been done early enough to make sand bag emplacements. I guess the shock of the war starting without any forewarning had really fouled up what little organization there might have been.

Soon, about 0230 (the time went by so fast at the time that I never could figure where the time went between 0100 and 0600 in the morning when we surrendered), the first Japanese sortie into the Plaza started. Though we had few good weapons, we moved down about fifty as near as we could see from the moonlight. They fell back and came again stronger, maybe an hour later. This time they were wiser and sent in an advance patrol who naturally drew the fire of the two Lewis guns. That was the end of those guns, crews and all.

The Japanese concentrated their fire on them and got them all and fixed the guns. However, we gave them more than they had expected and drove them out of the Plaza again. We had quite a few casualties. However, I was lucky, being hit only by ricochets and splinters. Soon another attack was made, this one being preceded by mortar fire. Their aim was bad and most of the mortars missed the Plaza, otherwise they could have walked in upright as they sent in enough to kill 1,000 where we were less than 100.

Prior to this last assault, the Governor decided we had done about all we could to make a token show of resistance and various patrols who had escaped the Japanese were in with reports indicating the large number of Japanese, which we later verified. The decision was to make one more show of resistance taking as many as we could (since we were unsure if the Japanese would honor a surrender for many of us in the service in Guam had been in China from 1931 on and had seen how the Japanese never took prisoners) and then try for an honorable surrender.

Well, that was the lowest moment in my life when we received the order to destroy whatever weapons were still serviceable and fall back to the so-called Palace (so named because of the Spanish days). But orders were orders and we did as we were ordered. A Marine Officer (the Chief of Police on Guam) was given the unenviable task of making the surrender offer to the Japanese. Surprisingly the Japanese ceased fire and soon surrender was arranged. A mighty low moment.

Japanese prisoners

The next hour is like a nightmare yet. The Japanese troops were pretty shaken up. I will always suspect that they expected no resistance here in Guam at all. These troops, we later learned, were really a landing force for taking Rabual in New Guinea and had used Guam as their last full scale landing practice. The Japanese intelligence had a pretty good layout of Guam. They had a better map than I have ever before seen of Guam. (Their intelligence had called me in for questioning after the island fell and I was shown their map.) They knew we had no real defense forces ashore here, and therefore I suppose they thought they would take over without a shot.

Anyway, the troops were so shaky that they ran us through a double line of troops, a gauntlet, Indian fashion; and swiped at us with bayonets and gun butts. One unfortunate lad right behind me was killed. Others lost part of their scalp; one bled to death later from a bayonet cut across the back. One of our wounded, who had been shot through both ankles, was used as a kicking target on his ankles. One poor guy later lost his mind.

And then they stripped us naked and made us lie in the sun until 1100 that morning without medical attention, or even a little water. These were bitter moments for the old timers among us. Before the day was over, they herded us into a building and permitted us to get back some clothes and then the next day we were all locked up in the Cathedral and served two skimpy meals a day. A few brave Guamanians managed to smuggle in a little food and medicine.

Near Christmas time, the Japanese let Maria come to the Cathedral for a short visit to bring me food and cigarettes. Later events showed she needed this worse than I did. Since she was married to an American service man, she was barred from our home, and couldn’t even get in to pick up cooking utensils or anything. The Japanese had moved into our house, using it as an officer’s quarters.

Just before we left Guam for Japan on the Argentina Maru, Maria was allowed to see me once again and this time she was permitted to bring the children. She already showed signs of the hardship she was suffering, being force to live wherever she could find someone able to take her in. Everyone was in bad shape by the end of that first month, because the island was thoroughly disrupted and the Japanese were reorganizing the island as they wished. No crops were being grown. Business was at a standstill, and very few people had enough food. They had to fall back on the Japanese; and the families of the American service men were naturally at the bottom of the list.

The Japanese even had the gall to suggest to Maria that her troubles would be over were she to submit to being placed in a Japanese Army “Entertainment Group.” Well, Maria has a mind of her own and a temper that matches any good Irish temper any day. I guess she didn’t improve her standing with the Japanese when that suggestion came up. Actually, Maria lived in eighteen different places during the war, and these were only temporary spots permitted her use by the charity of those who had the places. Maria and the four had it pretty tough.

But to get back where I was: We were kept in the Cathedral for about a month. Then the Japanese marched us five miles to Piti and into the Argentina Maru, a troop transport (she had been a liner but was now a troop carrier) and off to Japan. We went in tropical clothing being told that where we were going no warm clothes were needed. (We didn’t have any anyway.)

We soon landed in Japan in the dead of winter. I have only a hazy recollection of those first weeks there. It was rugged trying to get used to the sudden change in climate on soup only, three times a day (horse bones with Chinese cabbage and miso). We had the trots so bad that the toilet facilities had to be tripled in the first three days. Then when they had us pretty low (They were cagey, those characters), they commenced to treat us better and gave us bread and some solid food and put us in Japanese discarded army uniforms, World War I or older, I believe.

You should have seen us taller men in those short-legged pants and small coats. My pants reached my knees and the coat sleeves reached my elbows. I laugh lots about it now, but boy, that was sure hard to take to have to accept a Japanese uniform at the time, especially so soon after having been in our own uniforms. I think we all had a guilty pang over that, but self preservation had taken hold of us and the pride of uniform did not keep us from accepting anything to keep from freezing.

Even then it was so cold for all of us that we doubled up at night when trying to sleep under blankets made out of paper (yep, they were made from paper and the Japanese threatened to shoot anyone who let water get on them). A break for us was the appointment of an old retired Japanese Colonel as head of the prison camp and the old boy had a heart and soon we had some small coal stoves for heat. And we soon were permitted to take a bath (did not have one from the time we left Guam until a month after our arrival in Japan) and three meals a day of rice and soup as our fare.

Zentsuji POW camp

We soon adjusted to the change in diet and the trots stopped, and then came the assignment to work detail. By May of that first year we had terraced a mountain about three miles from the prison camp. We thought we were going to raise our own food. We were wrong. The Japanese army had food raised there all right, but not for us prisoners. Had we known, we would not have done such a careful job of the terracing. We didn’t feel too badly at the time though, because we were all great optimists – we were sure the war would be over in a matter of days or weeks. As a matter of fact, we were really the supreme optimists while still in Guam. Even right after Guam fell, every time we heard a plane we were sure it was some of our boys coming to take over again. What a long wait we had in store for ourselves.

We soon realized in Japan that we might be there a while; and I for one decided to look into the prospects and determine what was best to do. Already some of the men were going off the beam, despondency being their worst enemy. After weighing all possibilities I decided to make a stab at learning the language. My reasoning was that surely this was a subject they might let me have some textbooks on. My reasoning proved correct.

As the prison camp settled down into some sort of routine, when the prisoners commenced asking for textbooks to use in what little spare time they had, so as to keep from going stir crazy, the Japanese at first refused the requests. Several of us asked how about the Japanese language. We were not too surprised to have our request granted. Luckily we had an interpreter, an American-born Japanese who had been caught in Japan when the war started and who later turned out to be a secret American sympathizer, but who also had to hide it most carefully; otherwise he would have lost his head, and he took us in hand. Well, I studied the lingo throughout the war, and by war’s end was actually acting as the prisoners’ official interpreter.

Of course today I don’t speak the language as fluently as I did in 1945. Haven’t used it enough, though I find I still have enough grasp of it in the Trust Territory (Micronesia). But by studying the language through out the war, I managed to keep my mind well occupied and alert. There were several of us who did this. One of our Naval Language experts who had been captured later on in a naval battle in Java was an expert in Japanese and he took over the teaching. At war’s end he tried to get me to go to a language school in Denver to polish off my learning. However, my only desire after the war was to get back to my family and forget all about Japan. As it was, Washington decided for me anyway. They had all the language students in Japanese they needed when the war ended, and I couldn’t have gone had I even wished to.

During those early months, the Japanese tried to get us to sign statements we would be on our honor not to try to escape, would never insult the emperor, and so on. We managed to buck all this as a body, sometimes being on short rations that were already short, because we were so stubborn.

International Red Cross

Gradually it developed that our prison camp would be the one the Japanese used as an example of their camps to be shown to the International Red Cross. This was a break for us since it led to better treatment, improved food, the installation of medical facilities, and men were permitted to study various subjects that the Japanese considered non-military.

Even a library was set up, though I will admit it was a library that must have been selected for a bunch of morons. The laughable thing about it now is (though at the time we didn’t think it was funny) the way the Japanese used to put on a pretty good meal the day the Red Cross people were due in. I’ll never forget our consternation when one Red Cross group got delayed at the last moment and failed to show up at the appointed date. They came the next day. The result was that we had good food for two days running. But, boy, did we pay for it during the next few weeks.

An odd thing concerning the International Red Cross was the way the Japanese kept the POWs from talking directly to the Red Cross people. Instead of permitting uncensored discussion with the Red Cross, the Japanese would appoint a prisoner committee, and invariably the committee was composed of the collaborators. It was for this reason that we never were able to check on the lack of mail.

The Japanese paid us for our work, presumably in accordance with international law. However, the law states each military prisoner who is required to work will only work at a job suitable for his military rate or rank. Well, I was a chief when the war started, but the Japanese forgot about all such things. They worked us according to our physical condition. The pay was something. I got fifteen sen a day. With the yen worth about 360 yen to the dollar after the war, that meant I was working for nothing. One American dollar was worth 36,000 sen, and I got 15 sen per day. You figure that out.

However, the officers were paid about the right equivalent of their rank in the early part of the war, and we soon had several million yen floating around the camp and nothing to buy. Some of the boys managed to organize a poker game and it lasted off and on in various hideaways until the cards wore out. You should have seen that deck of cards after it was used about two years. The deck was about six inches thick. You couldn’t shuffle it at all. And you should have seen the players try to hide the cards in their hands. They were all identifiable. In stud poker when an old dog-eared ace or joker was on the top of the stack, everyone knew it, and the way some of them tried to buy pots on the strength of that top card was something to see. When the war ended the U.S. Government let us turn in 200 yen each at the rate of about ten to one, I believe it was. We had one character who had dealt in the black market all during the war, having several good Japanese contacts outside the camp. And if he had one yen, he had a million. He had hoped to cash in, but was sorely disappointed when he learned only 200 yen were exchangeable. Such were the fortunes of war.

Another interesting sidelight on the International Red Cross was that in the early days of the war, in one of the few opportunities, a prisoner found a fleeting chance to talk to them. The matter of our being permitted to have Mass was brought to their attention. By Christmas 1942, we were allowed to have Mass, first for Christmas, and by Easter time in 1943 we had finally worked around to daily Mass. An Australian Chaplain, Father Turner, a Jesuit, was with us.

We stole the flour from the Japanese for making hosts, that being my special task. It was rather difficult, but I worked it out where I used a steel bolt with a round flat head which I heated in the ranges under the pots along with a piece of sheet metal. I would make hosts whenever the chance came, because the Japanese permitted Mass but wouldn’t let us make hosts out in the open. Doing this in a clandestine manner didn’t seem wrong to any of us. As for Mass wine, Father Turner managed to arrange for some through a Japanese Catholic priest. Father had asked the Japanese to permit a priest to come into the camp to hear his confession, and somehow he arranged it with the Japanese priest. The wine, along with a few other needed items, somehow came into the camp. Just how it was arranged we never did learn.

Having daily Mass, until Father Turner was taken away in early 1945, was the greatest blessing we had. Many non-Catholics in the prison became Catholics. At one time we even organized a Holy Name Society in secret (unknown to the Japanese), but eventually had to stop when one of the collaborators spilled the beans on us. We had been using what was supposed to be an abandoned outhouse for our meetings; and the Japanese would never have suspected it.

I lost track of Father Turner after he left Zentsuji, but I still hope to someday get in touch with him. That diary I had kept included his address as well as many others from New Zealand, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Canada, and the U.S. After the war, I tried reaching him by sending letters to a few addresses I thought I had remembered correctly. But they were all returned to me.

I should bring in some praise for how the International Red Cross did do some good once they were acquainted with any facts or problems. They were greatly handicapped by the intentional hindrances given them by the Japanese. After the war, when talking to some of them at Wakiyama, we learned it had been the same in all the POW camps.

Boiled horse bones

As for food in the prison camp, it was a shame the way we boiled those poor horse bones that first six months there. We used to stack them up like cord wood and from experience we soon learned how long to let a given batch of bones rest before putting them in the pot again. The pots were big black kettles like we see or did see at hog killing time when we were young. Each batch of bones was labeled, and when their turn came, into the pot they went; and each successive use saw more of them broken up and pulverized to get the calcium.

After the first two months or so there, we all started losing the fillings from our teeth. Some of the less fortunate lost most of their teeth while there. I was pretty lucky. My teeth lasted until the war was over, though I did have to have every filling replaced. One of the prisoners who had had dental experience dug up some white-looking cement and filled my teeth when the regular fillings fell out. After the war, I started losing teeth though and today I have eleven missing. Suppose I should have a plate or two put in, but haven’t bothered about it yet. The rest are still pretty good.

Some of the more unlucky ones at the prison camp lost their teeth by other means. Some of the Japanese took delight in knocking out teeth. When my turn came for a beating, they hammered my chin. I carry a few scars but I also have the satisfaction of remembering one Japanese making me stand at attention while he wound up and let me have it, and he picked himself up off the floor while I still stood. It was the mule in me I guess, but I was just as mad as he was; so I made up my mind I would take that blow, if it were the last I ever took.

Of course I lived to regret it. That pipsqueak made life miserable for me until he was transferred. I carry a scar on my shin where he played Yankee Doodle with his hobnailed boots one winter night when I saw him trip over a stump and laughed at him. Another time he got me on the shins when he caught a Japanese guard stealing a wristwatch one of our shot-down aviators had managed to keep. It was the only timepiece we had among all the prisoners and was invaluable to us. When the complaint was made to the Japanese Commandant, he naturally tipped off the guard to get rid of the watch, then made us go out and inspect the guard house, their gear, and everything they had. We didn’t find the watch and didn’t expect to find one, naturally. Boy, did the Japanese then hold a field day on us. I was into it because this little Caesar, as we called him, got in his licks on me that time too.

After the war, during war crimes trials, he got twenty years for several of his cute little tricks at our prison and others. I had been called as a witness to the beating of an Australian Army Officer, but a deposition was accepted and I didn’t have to go back to Japan.

The only thing that bothered me was the fact that I was used to putting up my dukes when someone wanted to tap me on the kisser, but there you couldn’t very well do it because in these affairs a guard stood behind you with a fixed bayonet.

By early 1942 the prison camp was soon settled down to a routine, if you could call it that what with being mustered all hours of the night. We had been pretty checked over and were assigned work details. Most of us were initially working on terracing Backbreak Mountain. Soon, however, many of us were put to stevedoring on the docks and railroads twenty miles away.

We left camp for work at 0400 in the morning and arrived back there at 2000 at night. A water shortage developed shortly after we arrived so a detail had to haul wood barrels on a kuruma (wheeled cart) about five miles to get enough water for the soup we had three times a day.

Bath water was nonexistent, and about once a month enough trickled through the line to fill one Japanese style bath – a big tub about six feet by eight feet. You would at first think that was plenty big enough. But when you stop to realize that the Japanese camp staff took their hot bath first always, even though they had their own ofure (bath) in their outside barracks with water to waste they used our bath first to let us know how inferior we were. Then we went into the tub in relays of twenty men. As the camp reached a total of 800 and more, those who were in the last group to get a bath really had a mess on their hands. However, we all got a crack at the last group in, and we had to be satisfied or do without. By summer time when we were stevedoring cement for thirty days or so without a bath, you can be sure on one turned down that bath, no matter how dirty it was. Then to add insult to injury, the last in the bath had to clean it up. The first time I was in the last group it was a wee bit squeamish, but I soon got over it.

Later on in the winter of 1942-1943, water became more plentiful; so we were permitted a bath once a week, but the same water for over 800 men held true. It was that way throughout the war. Sometimes the number of prisoners fell well below 800 and then we rolled in luxury in that community bath.

When the poor devils from Bataan arrived, that is, about 200 or so, they had body lice so bad that the Japanese wouldn’t let them use the bath until after they had been decontaminated in the crudest methods ever invented. It took a week and it was wintertime. A number of them caught pneumonia as they had been on shorter rations than we. Those with pneumonia died eventually, as we had no real means of helping them. The Japanese cremated them. The best we could do for the poor unfortunates was the fact that everyone who was not sick donated a teaspoon of his soup of rice to give them a bulky meal. The type of food didn’t do much more than cause more complications, as they were already too weak to digest the coarse nourishment.

The nighttime musters, which were held without warning, were rough, especially in wintertime. To make it pleasant for everyone, we had to count off in Japanese and some of the fellows never could learn to count to twenty (they put twenty of us to a squad room in old World War I barracks.) The Japanese would require counting off over and over until the numbers were pronounced to their satisfaction. You can be sure after the first year or so we could count in Japanese as good as the Japanese themselves. Once or twice some of the fellows farthest away from the Japanese guards tried counting off for our boys who had some difficulty. That resulted in the one caught being sent out into the night to pace up and down the camp roads. In the summer time it wasn’t so bad other than for the mosquitoes, but in winter time it was not pleasant, to say the least.

I mustn’t forget to tell you about how we fertilized the crops for the Japanese with “night soil.” This was another phase of our life there, which required quite a bit of adjustment to become used to. But we all became very proficient honey dippers. There may have been weak stomachs, but hunger had chased away all this by the time we were introduced to this time honored method of fertilizing. I didn’t mind too much as I had seen it for so many years when on the China station.

As was bound to happen when hunger was uppermost in everyone’s mind, we all became experts in stealing from the Japanese. The only trouble was we were doing all our stealing from the military, and they had laws there during the war that included the death penalty and applied to their own civilians as well. Food shortages were bad after the first year. However ninety-nine percent of our smuggling systems worked very well and we were able to supplement our small ration this way. Sometimes a tasty tidbit came in, but this went to the sick by unanimous agreement, that is, unanimous among the safe POWs. Yes, we had a few who sold out to the Japanese, and until we had them spotted, life was miserable, for many well laid plans in the early days fell apart for some unknown reason, which later developed to be the collaborators selling out their fellow POWs for an extra bowl of rice. However, the one percent that did get caught paid heavily. The Japanese knew we were stealing; so when they did catch someone they made a horrible example.

In our camp we had only one death from this cause. A British aviator from Singapore was found with several rolls of tobacco leaf, and tobacco was the Army’s sole property in Japan in the leaf. So they knew they had this poor man cold turkey. He had obtained it from one of my own shipmates off the Penguin who had stolen it in an Army warehouse by going through the fences at night. The aviator would not squeal on him; so the Japanese threw him inside the so-called brig of the POW camp without clothes. It was dead winter, and he caught pneumonia and died a few days later. The Japanese officer responsible for that received a twenty-year sentence after the war.

Some of used to steal little cakes and cookies right under the Japanese noses when they had some of us working in a bakery preparing sweets for one of their Army hospitals. It finally got so serious that the Japanese took us out of the bakery and they never did learn how we managed to pilfer the sweets, thought they shook us down frequently. We had managed to work out a fast switch system, one to the other, among ten or twenty prisoners working at the bakery. Diverting their attention was simple enough. Over-under the fence delivery route was cleverly camouflaged, being a box buried in the ground and untouched daily until well after dark.

The Japanese also tried to teach the POWs how to bow Japanese style. We were required to bow to all military, as were the Japanese civilians for that matter. Many a Japanese temper was rubbed raw before they finally settled for a bow we secretly referred to as our “Nertz to his nibs the Emperor” bow said each time the despised bow was necessary. We had no choice in the bow deal. Even Japanese civilian got slapped around if they failed to bow when passing military personnel or one of the hundreds of War Dead Shrines. I laugh now, but during the early days as a POW we all had lots of knots on our heads.

One might think that no Japanese were any good. However, they were good as well as bad, and before the first year was out we had several Japanese civilians smuggling medicine in to us.

Be happy, cooperate

In the early days of the war, when things went well for the Japanese, they used to line us up at odd times and read off proclamations a mile long telling us how we should be happy and cooperate as we would spend the rest of our days there. As time went on and things looked grim for them, they reached a point where they forbade us to smile or whistle. Soon they started digging bomb shelters (we dug them) and we naturally thought some would be for ourselves. We were only kidding ourselves. When the bombing started the Japanese all ran for the shelters and the guards on duty herded us to the upper floor of the barracks. A rather pleasant feeling.

Men at work outside in the damp were simply herded together out in the open. At first we were nervous, but after a while we realized this didn’t do any good. Our camp was never hit by bombs, though Takamatsu, a nearby city, was fire bombed and burned out completely. That was a city of 100,000. Later we learned that 60,000 had died there. Other POW camps were badly bombed.

One thing that used to try us all was when, during 1943, the Japanese set up a chicken and rabbit raising project, intended for the prisoners. After everyone pitched in and got the project going, the products went to a Japanese Army hospital nearby. However, on rare occasion we did get an egg (every New Year’s) and rabbits that died were ours to eat.

After the big mountain-terracing job had been completed, the Japanese kept a small crew of prisoners on that type of work throughout the war. Once in a while I was put on that detail too, and throughout the war we always kept a sharp lookout for snakes. Snake meat is rather dry, but when a man is hungry it beats even a filet of steak. Cats and dogs became non-existent in our area after the first year. Some of the men rigged deadfalls and caught all of them. Dog meat is not too bad; but I never could get used to that stringy cat meat.

One time during the war the Japanese gave a big steak dinner for us. I was chief cook and bottle washer at the time, and it was some job to cube the carcass (the poor animal must have starved to death, but we asked no questions), which measured in grams only. These big steaks weighed exactly thirty grams each; and we in the galley (it was more like a foundry really) worked all night weighing it out. But it was good, at that.

For a long time before that, we had been getting by on fish once a month. The Army gave us their rotted fish rather than throw it away. Our best source of food was the Army guards’ garbage can. As hunger became stronger, it got so bad that we were fighting like animals over that garbage. And finally we had to work out an arrangement whereby each squad room took turns at the garbage can. This smoothed things over nicely, but then the Japanese had lost their daily show in our fighting over the garbage; and to show their kindness they moved the garbage can outside the camp.

A big event for the smokers, including myself, was the monthly ration day on cigarettes. Before the war, I had smoked a pipe, but also used up to two packs of Luckies a day. That ration in Japan was one pack of ten cigarettes a month. And when a man is hungry, a smoke seems to ease it. It was wonderful getting all sopped up with that cheap Japanese tobacco one day a month; but for the next month we all had nicotine fits. The non-smokers did quite well trading their cigarettes for food. We had four die from starving themselves by trading badly needed food for cigarettes.

We made pipes from cherry wood when working in the mountains (it was a crime to steal wood of any kind as it belonged to the Emperor), and once in a while we managed to get tea leaves which smoked quite well after we got used to them. I still have my cherry wood pipe. Also my wooden bowl and my POW tag.

As the war continued, food became so scarce that rice was taken from us. We then substituted rice part of the time with soybeans, which were rich in protein. The bean was too rich for us at first, and really gave us the trots. The Japanese would only let us have them about twice a month though because of the wood required to cook them. Try boiling some soybeans and see for yourself how long it takes to make them soft enough to eat without any teeth or all the fillings gone. We had no soda or anything to help soften them, so had to boil them steadily for seventy-two hours.

On the other days we substituted rice with the grain sweepings off the dock. That mixture had everything from horse manure to nails and glass in it. It didn’t take long for the more ingenious to rig a good old fashioned washer similar to what the good panners used years ago in California. A few fine rocks remained a few men broke off what teeth they had left. Those dock sweepings had been used before that for feeding the chickens and the prisoners who worked there had worked out a system whereby they took turns watching for Japanese while some of the men sorted out the edible grains. This grain, however, all went to the sick.

An old Army Captain from Bataan with some chemistry knowledge managed to work out a concoction of clover leaves mixed with hulls of grain, which was found to help an awful lot in reducing Beri Beri. I have often wondered what happened to the Old Captain. He was pretty well wasted away when the war ended.

Toward the end

In 1944, when things began to get really tough for the Japanese, they didn’t seem to care much whether we lived or not. So all summer long we lived on eggplant soup. Man, that was something! We were allowed only a few pounds of salt each day and we needed actually fifty pounds or more, as the camp was full. So the soup was flat and hard to down. But hunger brought us around. That fall we commenced eating the leaves from the eggplant, which had been saved. When they ran out, we started on sweet potato vines (dried). Those were really something.

When the Japanese found that we could live on those dried vines that was our major food item from then on until the end of the war. Red Cross food packages had been brought into Japan, but it took a long time for them to reach us. The Japanese couldn’t face the fact that those little boxes were full of life-saving food items which they themselves didn’t have in the Army. As I recall it, I received three of these packages during the last nine months of the war. We later learned that there were enough sent to Japan through the International Red Cross to feed all the prisoners with one box each week. A Japanese Army Captain in our camp got fifteen years for withholding those packages from us. That last winter we also received some warm clothing through the Red Cross. But once again, there was not enough to go around. We later learned there was plenty for all of us, but the Japanese held it up.

In the early part of the war, before the Japanese forbade whistling and laughing, they had permitted the prisoners to organize some entertainment groups. It was surprising how talented some of those scarecrows were. Despite being weak from hunger, beri beri and diarrhea, these men really put on some fine shows. For several months the place actually became bearable. The old retired Japanese Army Colonel was still in charge of the camp and he had permitted this relaxation. How those men ever found the energy to get together, make up programs, and practice them is beyond me. But they did it and to the dying day of every man who was there we will always have a warm spot for those men. Later several of them died, probably from malnutrition, though the Japanese always had an official cause of death, attributing it to some contagious disease.

Another interesting but dangerous pastime we had, after several of us had learned the lingo fairly well, was to steal Japanese newspapers and translate them. Five of us did that little job, each of us having a certain part of each article to work on, doing it in different places in the camp. Of course we never knew how true the articles were, because the Japanese sure fed their people a lot of hot air later in the war. In the early days they could publish good news no doubt; but later there was nothing but bad news.

Only three months before the war ended, I recall translating an article that told how we had lost our entire carrier fleet in the Marianas, and there was talk of an armistice as the U.S. forces were about washed up! However, they did publish the truth about President Roosevelt’s death and even let us have a memorial service for him in the prison camp.

During the last summer there, the ill effects of living on dried sweet potato vines and dock sweepings finally commenced showing up in a big way. Everyone seemed to be sick at once. The Japanese felt the same way about human beings as they did about their work animals; if sick, cut down the food. If they died… oh, well.

Just before the first A-bomb hit Hiroshima, I came down with whatever it was. I was blacked out for eight days. I snapped out of it though and went back to my pots in the galley. We were down to a rather small group at Zentsuji, so I fell heir to cooking for the entire camp. Of course it wasn’t much of a job cooking vines and sweepings. The only trouble was that I had to get up at 0100 and did not get out of the barn until 2000 every evening. I was tired and didn’t care much for the long hours.

Commencing on the Feast of St. Joseph, March 19, 1945, was when our area really started to catch it from the bombs. From that date on we all learned to be very wary around the Japanese. They were so sensitive that they were snapping at one another. When Hiroshima was hit, we of course had no ideas what had happened, though we could see the flames. The Japanese didn’t know what had happened at first either. This was proven by their intelligence coming into our camp and questioning us very closely.

I could well imagine how we could know something about an A-bomb. We didn’t even know what the jelly gasoline bombs were until some evacuees came through on the railroad and those of us who could speak the lingo managed to ask about the badly burned people wrapped head to foot in bandages. From their answers we soon put two and two together and figured out what it was. Those napalm bombs really had the Japanese civilians jittery.

After Hiroshima, the Japanese were pretty touchy with us, though they did seem to have a little more interest in our welfare. The only trouble was that their own people had nothing and they couldn’t do much for us either. We had a hunch that the end was near because of the fact that several of the meanest guards suddenly disappeared right after Hiroshima. It was a good thing we were becoming optimistic, otherwise we would never had made that last month. I was down to 120 pounds after dropping from 175 pounds at the start of the war. However, I was in good shape compared too many. Beri beri had raised hob with almost everyone. But for some reason, after the second winter it never bothered me too much.

Soon Nagasaki got an A-bomb. This really shook the Japanese. The Kamikazes tried to get us. They were sworn to die for the Emperor and decided to take a few of us with them. The guard was doubled, which brought an end to this danger. All regular bombers kept splattering Japan everywhere. It got to the point where we never had any rest at all. Air raid alarms went on day and night. The Japanese home defense force was out all the time. Around our area their weapons were bamboo spears. We picked up rumors that commando units were expected to land in our general area. We were on Shikoku Island, on the inland sea.

The Japanese didn’t tell us the war was over at all. We found out for sure when most of the guards up and left, leaving their rifles behind. We organized the few Marines we had in camp into a security guard. Our only real worry was the Kamikazes as there were some loose on Shikoku. However, we were never seriously bothered. The day the war ended we knew something was a foot because all the Japanese listened to a radio broadcast, which we later learned was the Emperor giving the people the bad news.

It was funny the way the Japanese more or less left us to find out for ourselves. It was probably just as well. By the time we got the Japanese radio to working and picked up American broadcasts telling POWs everywhere what to do, the mean guards had put lots of distance between the camp and themselves. In some areas the POWs got their hands on the guard who had been mean, and that was the last ever heard of them.

Another peculiar thing that happened just before the Japanese left the camp, was their taking of our POW tailor aside and having him fashion an American flag of some cloth that gave him. He couldn’t tip us off on what had happened. They kept him away from the rest of us until they left. Then when the Japanese left and we had our radio going, we learned what was behind that. POW camps were told by our forces via our radio to spread flags on the roofs of buildings or on the ground at the campsite. Soon planes came over and commenced dropping parachute loads of food, medicine and clothing. Some of the parachutes failed to open. In our camp, one load of shoes went clean through the slate roof, two floors of a building and buried themselves in the ground under the building.

A case of peaches from another load that had a parachute failure hit a brick structure. The case didn’t even break open. But every can inside was found bone dry. The impact had been flat on the bottom of the case and the cans were found to have fine slits where they burst and ejected the contents. It was hard to believe, but I saw it with my own eyes.

With these friendly bombs falling all around, we didn’t know where to go. In or out of the immediate camp vicinity was not safe. Many drops fell outside the camp. It was interesting to see how the Japanese civilians, organized by the mayor and police of the nearby town, gathered up every single item; and to the best of the POWs knowledge, they brought every bit of it to the camp.

The only casualty we learned of from the bad drops was over bear Kobe. A Navy carrier plane dropped a gasoline drum full of canned beer on a makeshift chute; and it didn’t work, and the drop struck a woman on a hillside, burying her.

For the first few days, other than keeping a close guard on the camp, we all sat around eating till we were ready to burst. It was a wonder we didn’t kill ourselves. Quite a number had not only indigestion but the trots as well. I played it cautious and tried to eat a balanced diet, but it was hard to resist eating mountains of the food we had not seen in so long. The most amazing thing was the way we gained weight. I gained nearly 40 pounds in a month!

It was over a month after the war ended before an Army Rescue team found us. We had been instructed by radio to remain where we had been as POWs. The orders were repeated for a week or so: “Don’t under any circumstances move from the spot where you were held as a POW.” So we stayed put. However, within a week the Japanese civilians sent delegations to the camp telling us they invited us out to various homes for small parties. We held a powwow and decided it was safe; and thus all of us did have a look-see at some of the countryside as sightseers rather than as POW work detail.

You may have seen some of the pictures taken of myself and other POWs right after the war. Most of these were taken nearly a month after the war ended, and in them you can see we were putting on weight. The food and supply planes, all the way from B-29s to little fighters dropped enough supplies in our camp area to supply 1,000 men. They must have had bum dope. At one time we had close to 1,000 men in the camp; but at the war’s end there were only about 125 remaining.

You can well imagine the temptation to overeat was enormous because of the large supply of food. We tried to curb it by the older and senior men giving orders to lay off, even going so far as to set up a rationing system, liberal in quantity, but nevertheless rationing. You can imagine how receptive most were to rationing after having been on short rations so long. The system helped avoid criminal waste though, and a few days before the Army Rescue team got to us, we had given out limited quantities of food and medicine to the Japanese civilians who had helped us during the war. The poor creatures wanted to accept so badly it was pitiful; but they were deathly afraid of being accused of stealing from us as their own army would. However, we set their worries at easy by making up signed statements attesting to the fact that we had given the individual the goods in thanksgiving for their assistance during the war.

Actually, if it hadn’t been for an old man by the name of Shirakawa (White river in English), I probably wouldn’t be here today. I was in pretty bad shape in the winter of 1944 and he smuggled in some medicine that pulled me through. If I ever go to Japan I will make it a point to look him up, if he still lives.

Well, after the Army Rescue team came in during the middle of September, they gave us all a very thorough medical check up. Each rescue team had doctors and nurses. And we prepared for the trip out of Japan. I was found fit to travel as an ambulatory patient. We were all classified as patients. Thus, I was able to do a lot of sightseeing in the long slow trip by train from Zentsuji to Takamatsu, then across the inland sea by ferry, then by train to Wakiyama, a pre-war resort town converted into a evacuation center, that is, what was left of it.

During the 400-mile trip from Zentsuji to Wakiyama every town we passed through was burned out completely. It was odd to note how our bombers had avoided the railroads while at the same time they wrecked everything along the railroads. They must have done some pretty good precision bombing. In Wakiyama, the whole town was destroyed except several huge hotels on a point at the edge of the town. These hotels were the evacuation center. There, teams of doctors numbering about 20 each, all specialists, gave us a real checking over, and then our intelligence people commenced their questioning regarding atrocities. It was all tiring, but we didn’t mind, as we were free men on our way home.

I was found to be in good shape other than being under weight, with bad teeth and bad eyes, and enough effects from beri beri to warrant a series of some kind of shots, which ended several months later in Guam.

Anyway, I was permitted to leave Wakiyama right away and I returned to Guam via a destroyer.

Back to Guam and family

Upon arrival at Guam I had to enter the hospital, as were all ex-POWs when they arrived at their final destination. After being checking in and squared away, I commenced the tedious task of fighting red tape to obtain permission to leave the hospital to try to find Maria and the children.

It was an odd thing that they had no records of the families of those of us who returned to Guam. For a while I was pretty worried because I had never received any mail from Maria during the war years. The Japanese had let her write regularly, but the mail never reached me. However, Mama’s cards and letters did reach me, at least some of them did. The Japanese also let me write to Maria, but she never received a single letter. It was the same with all of us who had families in Guam. I had no idea how Maria had fared during the war until after my return. I believe a priest who was a good friend of Father Michael had located Maria shortly after our troops had reoccupied Guam and had relayed word back to Mama and the rest of you through Father Michael. To this day Maria often talks about the things Mary sent her, which were a Godsend at that critical time when the only clothing Maria and the children had was the rags they had on their backs.

I arrived in Guam on December 19, 1945, and after a struggle from about 1000 in the morning until 2100 that evening, I finally located Maria and the children living in the same spot Cajetan found us, only the place was so poorly constructed at that time that a pig would have been insulted had he to live in it. I was so happy to be back and to find all safe that I quickly forgot the feeling of resentment which had struck me over the fact that we had more than 150,000 troops in Guam at the time and no one had given a thought to putting the families of the POWs under a decent roof.

After I returned, however, the picture changed. Had I accepted all the building materials and supplies, food, household equipment, and so on, that were offered, I could still be in business. However, I still lived in the pre-war days in my thinking and refused everything I couldn’t pay for. Everyone thought I was crazy, not only myself but also all the fellows who returned to Guam. Later we found out it would have been all right to accept all that was offered because when the demobilization started, the thousands of reserves who had charge of supply dumps couldn’t leave for home until their depots were disposed of. They made short work of that little obstacle.

Well, anyway, that should suffice for a brief incomplete answer to your question, Bill. I have probably left out many of the most interesting details; but it will give you something of an idea of what it was like. I laugh about it now, but I don’t believe I would want to go through it again.

However, I will say I learned many valuable lessons there. One thing, most important of all, I learned to be thankful to God every day of my life for whatever He brings to me or my family. I also learned to be patient and forbearing, something I most certainly was not before the war. I also learned that material wealth is for the birds. Spiritual wealth and health mean far more to me. Maria feels exactly the same on these points.

I will close for this time hoping, as always, that this little letter finds all of you in the best of health and happiness under the protection of Our Blessed Mother. Love from all the family,

Your loving brother,

Bob

For further reading

Mansell, Roger. “Guam Timeline 8 Dec 1941 to 31 Dec 1943.” Allied POWS Under the Japanese, WWII, last modified 2 August 2020.

––– “Roster of Guam Military, Native Guard, and Civilians Captured and Taken to Japan.” Allied POWS Under the Japanese, WWII, last modified 2 August 2020.

Palomo, Tony. An Island in Agony. Self-published, 1984.

Palomo, Tony, and Paul J. Borja, eds. Liberation-Guam Remembers: A Golden Salute for the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of Guam. Maite: Guam 50th Liberation Committee, 1994.

Thomas, James O. Trapped with the Enemy!: Four Years a Civilian P.O.W. in Japan. [Philadelphia]: Xlibris Corporation, 2002.