Folktale: Puntan Påtgon

Table of Contents

Share This

Legend of strength and envy

The legend of Puntan Påtgon (Child’s Point) is a folktale about a powerful man who becomes envious of his child’s superior strength:

Long, long ago giants are said to have lived in the Mariana Islands. Among them was a proud and strong man named Masala who lived on Guahan. He was the most powerful man in the Marianas and his strength could not be matched by any other.

Masala’s wife gave birth to a son. At first Masala was very proud of his child, boasting about him and presenting him to everyone. However, as the child grew into a toddler, people began to notice of his strength and power. Masala grew envious of the attention given to his child.

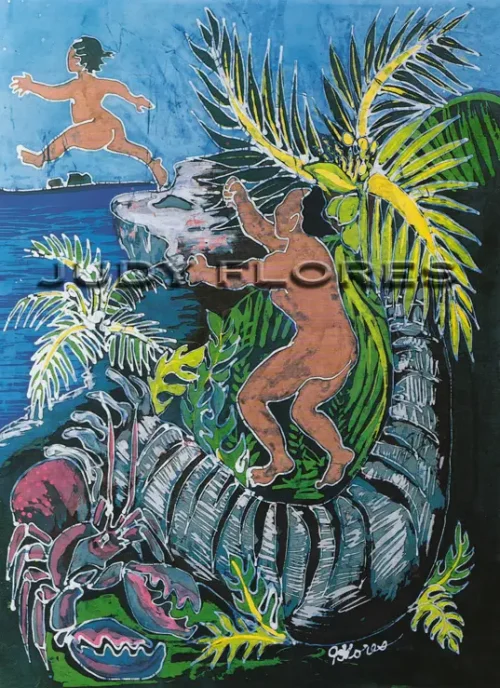

One day, Masala’s son caught an ayuyu (coconut crab) and spent many hours playing with it. Eventually, though, as crabs do, it disappeared into a hole near a niyok (coconut) tree. When the child noticed the ayuyu was gone, he reached down into the hole to get his pet but couldn’t get a hold of it. He grabbed the niyok tree near the crab hole and tore it completely out of the ground to uncover the hidden ayuyu.

Masala, watching the child at the time, was about to help his son fetch the ayuyu before he uprooted the tree. Masala flew into a jealous rage and went after his son. The little boy, frightened by his father’s anger, ran as fast as he could toward the northernmost tip of Guahan. When he reached Hinapsan (Jinapsan) Point he took a giant leap, landing on the southernmost point of the neighboring island of Luta (Rota), about 40 miles north of Guahan.

To this day, there is an imprint of a giant foot in the rock on Guahan believed to be the child’s and on Luta there is another footprint at the point where he is said to have landed.

Some believe that the child remained on Luta and became the great legendary Chamorro Maga’låhi Taga.

Cultural values

Ancient Chamorro Society author Lawrence J. Cunningham, EdD, writes that folklore:

…explains nature and human nature, and serves as a means to give expression to our emotions. Folklore tells stories about proper behavior and reveals what a culture values.

The legend of Puntan Påtgon can be interpreted to explain the concept of mamåhlao, which is a Chamorro traditional value meaning “to have shame.” Masala’s self pride and envy contradicted the value mamåhlao.

Robert Torres Tenorio argues that tales of the physical prowess of Chamorro men show that they were a strong people before the arrival of the Spanish in the late 17th century and how Chamorros responded to colonization. He states:

I subscribe to the opinion that these legends remained popular during the Spanish occupation because they reminded the subjugated natives of a time when the Chamorro was in control of his islands and roamed them with pride not even exceeded by their foreign intruders. The folklore that developed during the Spanish occupation is starkly different from that which preceded it. Tales of strength yielded to those of trickery and deception of the Spanish.

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Legends of Guam. ESAA Project, Chamorro Language and Cultural Program, Public Law 92-318. Hagåtña: GDOE, 1981.

Torres, Robert Tenorio. “Selected Marianas Folklore, Legends, Literature: A Critical Commentary.” MA thesis, San Diego State University, 1991.

Van Peenen, Mavis Warner. Chamorro Legends on the Island of Guam. Mangilao: Spanish Documents, Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 2008.