Map

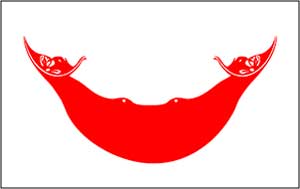

Flag

Quick facts

Official Name: Easter Island (Rapa Nui)

Indigenous Peoples: Rapa Nui (Polynesians)

Official Languages: Rapa Nui and Spanish (and limited English)

Political Status: Special territory of Chile

Capital: Hanga Roi

Population: 5,761 (2012 est.)

Greeting: Lorana

History and geography

Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, is a small volcanic island that encompasses about 67 sq mi of land mass, and at its highest point rises to about 1,700 feet. According to research and oral traditions, it was once covered with trees, which were all cut down, possibly to aid in the construction and transportation of the almost 900 moai or stone monuments for which Easter Island is most famous.

About 1,500 years ago, Polynesian Chief Hotu Matu’a led his people to the isolated island of Rapa Nui where they lived in isolation from the rest of Polynesia for many generations. Rapa Nui was likely settled by Polynesians who navigated in canoes or catamarans from the Gambier Islands (Mangareva, 2,600 km (1,600 mi) away) or the Marquesas Islands, 3,200 km (2,000 mi) away. They called their home Te pito o te henua, translated to either “the navel [or center] of the world,” or “the end of the land.” About a century ago, a visiting Tahitian thought the shape of the island reminded him of one of his home islands, Rapa Iti [Small Rapa], and he gave the island its widely known Polynesian name, Rapa Nui [Big Rapa].

The name “Easter Island” was given by the island’s first recorded European visitor, Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen, who encountered it on Easter Sunday in 1722, while searching for Davis or David’s Island. Roggeveen named it Paasch-Eyland (18th-century Dutch for “Easter Island”). The island’s official Spanish name, Isla de Pascua, also means “Easter Island.”

A series of devastating events killed or removed most of the population in the 1860s. In December 1862, Peruvian slave raiders abducted about 1,500 men and women, half of the island’s population. When the slave raiders were forced to repatriate those kidnapped, smallpox was introduced. Easter Island’s population was reduced to the point where some of the dead were not even buried. Tuberculosis, introduced by whalers in the mid-19th century, had already killed about a quarter of the island’s population. In the following years, the managers of the sheep ranch and the missionaries started buying the newly available lands of the deceased, and this led to great confrontations between natives and settlers.

In 1871, the missionaries evacuated all but 171 Rapa Nui to the Gambier Islands. Those who remained were mostly older men. Six years later, only 111 people lived on Easter Island, and only 36 of them had any offspring. From that point on the island’s population slowly recovered. But with over 97% of the population dead or gone in less than a decade, much of the island’s cultural knowledge was lost.

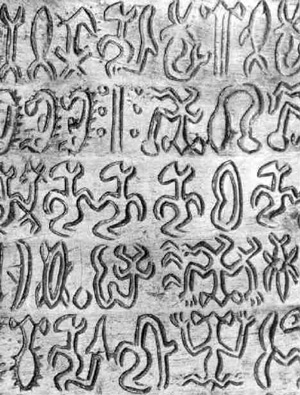

Alexander Salmon, Jr., a son of an English Jewish merchant and a Pōmare Dynasty princess, eventually worked to repatriate workers from his inherited copra plantation. He eventually bought up all lands on the island with the exception of the mission, and was its sole employer. He worked to develop tourism on the island, and was the principal informant for the British and German archeological expeditions for the island. He sent several pieces of genuine Rongorongo, an ancient writing tablet, to his niece’s husband, the German consul in Valparaíso, Chile. Salmon sold the Brander Easter Island holdings to the Chilean government in 1888 and signed as a witness to the cession of the island. He returned to Tahiti in December of that year. He effectively ruled the island from 1878 until his cession to Chile in 1888.

Easter Island was annexed by Chile in 1888 by Policarpo Toro by means of the “Treaty of Annexation of the Island” (Tratado de Anexión de la isla). Toro, then representing the government of Chile, signed with Atamu Tekena, designated “King” by the Chilean government after the paramount chief and his heir had died. The validity of this treaty is still contested by some Rapa Nui. Officially, Chile purchased the nearly all encompassing Mason-Brander sheep ranch, comprised from lands purchased from the descendants of Rapa Nui who died during the epidemics, and then claimed sovereignty over the island.

Until the 1960s the surviving Rapa Nui were confined to Hanga Roa. The rest of the island was rented to the Williamson-Balfour Company as a sheep farm until 1953. The island was then managed by the Chilean Navy until 1966, at which point the island was reopened in its entirety. In 1966 the Rapa Nui were given Chilean citizenship. As of 2011 a special charter for the island was under discussion in the Chilean Congress. Administratively, the island is a province of the Valparaíso Region of Chile and contains a single commune (comuna). Both the province and the commune are called Isla de Pascua and encompass the whole island and its surrounding islets and rocks, plus Isla Salas y Gómez.

Following the 1973 Chilean coup d’état that brought Augusto Pinochet to power, Easter Island was placed under martial law. Tourism slowed down and private property was restored. During his time in power, Pinochet visited Easter Island on three occasions. The military built a number of new military facilities and a new city hall.

The main community is now located at Hanga Roa (‘Great Bay’). Because of the US space program, NASA extended an existing runway into a full-length airstrip capable of handling an emergency landing of the space shuttle. Today, Lan Chile, the official carrier of Chile, provides regularly scheduled commercial air service to Rapa Nui.

Rapa Nui has no natural harbor, but ships can anchor off Hanga Roa on the west coast, the island’s largest village. In 1995, UNESCO named Rapa Nui a World Heritage site. It is now home to a mixed population, mostly of Polynesian ancestry. Spanish is generally spoken, and the island has developed an economy largely based on tourism.

Arts and culture

The people of Rapa Nui share a Polynesian heritage with their “cousins” throughout the rest of Polynesia.

The greatest evidence for the rich culture developed by the original settlers of Rapa Nui and their descendants is the existence of nearly 900 giant stone statues that have been found in diverse locations around the island. Averaging 13 ft (4 m) in height, with a weight of 13 tons, these enormous stone busts – known as moai – were carved out of tuff (the light, porous rock formed by consolidated volcanic ash) and placed atop ceremonial stone platforms called ahus. It is still unknown precisely why these statues were constructed in such numbers and on such a scale, or how they were moved around the island.

Some believe that the moai represented deified ancestors. It was believed that the living had a symbiotic relationship with the dead in which the dead provided everything that the living needed (health, fertility of land and animals, fortune, etc.) and the living, through offerings, provided the dead with a better place in the spirit world. Most settlements were located on the coast and most moai were erected along the coastline, watching over their descendants in the settlements before them, with their backs toward the spirit world in the sea.

Additionally, the people of Rapa Nui may have been the only Polynesians to have something akin to a writing system in the form of their rongorongo tablets, a few samples of which have survived to present times in widespread museums. The ability to translate them, however, seems to have been lost forever.

The islanders are good dancers, and have a great passion for music and dance. Popular dances are Sau-Sau, the island tango, the Tari-Tarita and other dances from Tahiti. Chants are performed by groups or popular singers of the island, who gather around their own musical instruments. They dance and sing, clapping their hands, moving their waists and their heads at the same time.

The native music is deeply rooted in ancient traditions and legends transmitted from one generation to another. In the imagination of the singers, folklore can be observed that is conformed by rural chants different from the current songs of Polynesian origin, which are more cheerful. One of these songs is the Sau-Sau, a popular song and dance of Samoan origin that has become a characteristic dance of the island. Additionally, there are other popular songs and dances dedicated to the gods, warrior spirits, to rain and love.