POP Cultures: Nauru

Table of Contents

Share This

Map

Flag

Quick facts

Official Name: Republic of Nauru

Indigenous Peoples: Nauruans

Official Languages: Nauruan, English

Political Status: Independent

Capital: Yaren

Population: 10,084 (2011 est.)

Greeting: Ekamowir Omo

Audio bite from Ewewi Zommy Tebouwa, Nauru

History and geography

Nauru is a 21 sq km (8 sq mi) oval-shaped island in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, located 42 km (26 mi) south of the Equator, between the Solomon Islands and Kiribati. The island is surrounded by a coral reef, which is exposed at low tide and dotted with pinnacles. The presence of the reef has prevented the establishment of a seaport, although channels in the reef allow small boats access to the island. A fertile coastal strip 150 to 300 m (490 to 980 ft) wide lies inland from the beach. Coral cliffs surround Nauru’s central plateau. The highest point of the plateau, called the Command Ridge, is 71 m (233 ft) above sea level.

The only fertile areas on Nauru are on the narrow coastal belt, where coconut palms flourish. The land surrounding Buada Lagoon supports bananas, pineapples, vegetables, pandanus trees and indigenous hardwoods such as the tomano tree. There are some seabirds, but no indigenous land mammals.

Nauru was one of three great phosphate rock islands in the Pacific Ocean. The others were Banaba (Ocean Island) in Kiribati and Makatea in French Polynesia. The phosphate reserves on Nauru are almost entirely depleted. Phosphate mining in the central plateau has left a barren terrain of jagged limestone pinnacles up to 15 m (49 ft) high. Mining has stripped and devastated about 80% of Nauru’s land area, and has also affected the surrounding Exclusive Economic Zone; 40% of marine life is estimated to have been killed by silt and phosphate runoff.

There are limited natural fresh water resources on Nauru. Rooftop storage tanks collect rainwater. Average rainfall is about 200 cm (79 in), but recurrent droughts can cause problems. Temperatures are warm and tropical. The islanders are mostly dependent on three desalination plants housed at Nauru’s Utilities Agency. Nauru is also susceptible to the hazards of global warming and rising sea levels.

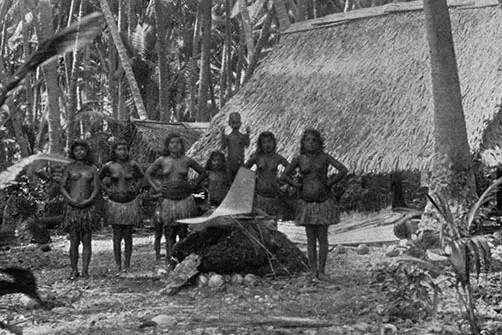

The Nauruans, who settled the island about 2,000 years ago, are a distinct people with their own language and culture. The Nauruan people called their island “Naoero.” The name “Nauru” was the way English language speakers heard it. The first westerner to visit Nauru was a whaling Captain John Fearn who arrived in 1798, giving it the name Pleasant Island. The people had little contact with Europeans until whaling ships, traders and beachcombers began to visit regularly in the 1830s. Europeans called Nauru “Pleasant Island.”

The introduction of firearms and alcohol destroyed the social balance of the 12 clans living on the island and led to a ten-year internal war, which reduced the population to around 900 by 1888; in 1843 there had been 1,400 people on Nauru. Peace was only restored when Germany took action to remove firearms from the island. The island was allocated to Germany under the 1886 Anglo-German Convention.

Phosphate was discovered a decade later and the Pacific Phosphate Company started to exploit the reserves in 1906, by agreement with Germany. The island was captured by Australian forces in 1914 and administered by Great Britain. In 1920 the League of Nations gave Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand a Trustee Mandate over the territory, though the island was administered by Australia. The three governments bought out the Pacific Phosphate Company and established the British Phosphate Commissioners, who took over the rights to phosphate mining.

During the Japanese occupation (1942–45) of World War II, 1,200 Nauruans were deported to work as laborers to Chuuk, Micronesia, where 463 died as a result of starvation or bombing. The survivors were returned to Nauru in January 1946. Nauru’s population had fallen from 1,848 in 1940 to 1,369 in 1946. After the war, the island became a UN Trust Territory, administered by Australia in a similar partnership to the previous League of Nations mandate, and it remained a trust territory until independence in 1968. The Naurauns had had a Council of Chiefs since 1927 to represent them in an advisory capacity to the Australian government, but the Nauruans pressed the UN and the government for further political power.

Anticipating the exhaustion of the phosphate reserves, a plan by the partner governments to resettle the Nauruans on Curtis Island, off the north coast of Queensland, Australia, was put forward in 1964. However, the islanders decided against resettlement. Legislative and executive councils were established in 1966, giving the islanders a considerable measure of self-government, including control of the phosphate industry, which occurred in 1970.

Nauru’s economy is based on phosphate mining, offshore banking, and coconut products to a lesser degree. Primary phosphate reserves were exhausted, and mining ceased, but in 2006–07, mining of a deeper layer of “secondary phosphate” began, though it is not as prosperous as the original layer. The other major source of government revenue is the sale of fishing rights in Nauru’s territorial waters. Nauruans also receive financial support from Australia, Taiwan and New Zealand, partially to rehabilitate the environmental damage caused by phosphate mining. Nauru officially joined the United Nations in 1999.

Arts and culture

Most people in Nauru live along the coasts in their traditional districts. About half of the residents are immigrant contract laborers, technicians and teachers. Migration into Nauru is limited, although Nauruans travel relatively frequently abroad.

Traditional culture is a mix of Micronesian, Melanesian and Polynesian cultures. There are 12 tribes, and while descent is matrilineal, there are some features regarding kinship and inheritance that are patrilineal. Intermarriages with other Pacific Islanders and Caucasians have resulted in physical changes among the indigenous people from their ancestors. Christianity is the dominant religion.

While the traditional culture has given way to the contemporary, as elsewhere in Micronesia, music and dance still rank among the most popular art forms. Rhythmic singing is performed at celebrations. Craftsmen make clothes, fans of coconut leaves and mats of pandanus. Designs are usually geometric symbols resembling those of Indonesia. There is growing body of work of stories, poems and songs.

A traditional “sport” is catching birds when they return from foraging at sea to the island towards sunset. The men then stand on the beach ready to throw their lasso. The Nauruan lasso is supple rope with a weight at the end. When a bird comes over they throw their lasso up, it hits and or drapes itself over the bird, which then falls down and is seized. The captured birds are often roosted as pets.