Map

Flag

Quick facts

Official Name: Republic of the Marshall Islands

Indigenous Peoples: Marshallese

Official Languages: Marshallese (Kajin M̧ajeļ, or Ebon) and English

Political Status: Independent, freely associated with the United States

Capital: Majuro

Population: 72,191 (2015 est.)

Greeting: Lokwe

History and geography

The Marshall Islands are near the equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the International Date Line. The country’s population is spread out over 29 coral atolls, and 1,156 individual islands and islets, arranged like two parallel chains running from the northwest to the southeast. The islands share maritime boundaries with the Federated States of Micronesia to the west, Wake Island to the north, Kiribati to the southeast, and Nauru to the south. About 31,000 of the islanders live on Majuro, which is also the capital.

The Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) was first settled by Micronesian navigators about 2,000 years ago. The Marshalls derives its name from British Captain William Marshall, who explored the area with Captain Thomas Gilbert in 1788. The atolls were not a cohesive entity until Europeans named and mapped them. The indigenous people called the islands Rālik-Ratak for the leeward and windward chains of atolls. The major inhabited atolls of the eastern or windward chain include Mili, Majuro, Arno, Aur, Maloelap, Wotje, Likiep, Ailuk and Utirik. The major islands of the western or leeward chain are: Ebon, Namorik, Kili, Jaluit, Ailinglapalap, Namu, Ujae, Lae, Kwajalein, Rongelap, and Bikini. Two isolated atolls, Eniwetok and Ujelang are west of the Ralik chain. The total area covered by the two chains is more than 300,000 sq mi (776,996 sq km).

There are no high islands among the Marshalls. Rainfall in the southern islands can average about 180 inches per year, such as in Majuro. However, there is much less rainfall in the northern islands, making them particularly vulnerable during periods of drought or El Niño.

The islands were controlled, in succession, by Spain, Germany, Japan, and, after World War II, by the United State. When the war ended with Japan’s defeat, the US was given administrative control under the newly formed United Nations, serving as a trustee.

For almost 40 years the islands were under US administration as the easternmost part of the United Nation’s Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI). The US performed nuclear testing on some of the atolls between 1947 and 1962, most notably Bikini and Enewetak. Exposure to nuclear fallout occurred on nearby atolls, leaving long lasting environmental destruction, health problems and social challenges for the Marshallese.

In 1986 the islands gained independence under a Compact of Free Association with the US. Under the terms of that agreement, the US provides significant financial aid that now exceeds $1 billion. The US uses Kwajalein for a military base, and from there, controls a missile testing range.

The modern economy combines a small subsistence sector with a modern urban sector. The subsistence economy consists of fishing and the production of breadfruit, banana, coconut and taro. In the northern islands, pandanus is substituted for breadfruit. Pandanus is also harvested for making handicrafts. There is also a strong service economy on Majuro and Ebeye as people who live on these islands have jobs at the US Army installation on Kwajalein Atoll.

Arts and culture

As with other Micronesian or Pacific Island societies in general, land is very important in Marshallese culture, and is the focal point for social organization. All Marshallese are organized into clans or jowi, and have land rights. The land is supervised by the Alap, or clan head. The chief, irojii, has ultimate control over the land and its resources and determines how those resources are used or distributed. Land is passed down through lines of matrilineal descent.

The Marshallese are skilled navigators, traveling mostly between islands of their respective chains or between chains. They also sailed over open ocean to Kosrae and beyond, to Kiribati. Their culture and social organization closely resembles that of the Caroline Island groups to the west. There are social ranks or classes, including the irojii lapalap or paramount chief; irojii erik or lesser chiefs; bwirak or children of chiefs, and the title, atok, given to men of special ability or accomplishment. Chiefly titles, however, can be quite fluid and can depend on an individual’s age, place in the birth order among siblings, and generational standing. Women often perform the duties associated with chiefly titles, and sometimes the term liroj is used to designate female chiefs. In general, as in other Micronesian societies, the roles of men and women are equal and complementary.

Most Marshallese are Christians of various denominations, though the largest church is the United Church of Christ.

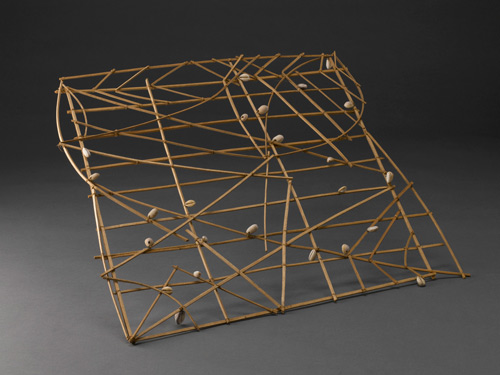

Probably the most well-known of Marshallese art is the stick chart. Stick charts were once used to instruct novice sailors of outrigger canoes. The meto was used for instruction only of ocean swell patterns. The rebbelib was used to show the placement of islands in the group or one of the chains. A third kind of stick chart, the mattang, depicted just a few local atolls.

The Marshallese also excel at finely woven pandanus and coconut fiber art such as baskets, trays, wall hangings and fans, produced by Marshallese women; in fact, these have assumed extraordinary value as images of national integration. Square-shaped mats traditionally served as clothing for both men and women. Handwoven, the mats often depict intricate designs that were similar to designs found in tattoos.

Before the arrival of missionaries, both men and women had tattoos, but only elite men could have their faces tattooed, signifying their high status. Tattooing was a long and painful process, but was a rite of passage into adulthood. Tattoo patterns were repetitive and abstract, often representing aspects of nature.

Outrigger canoe-making and creating shell body ornaments are also traditional art forms in the Marshalls. The stretching of earlobes was particularly intriguing for foreign visitors to the Marshalls because of the length to which earlobes would be extended.

The roro is a kind of traditional chant, usually about ancient legends. It is performed to give guidance during navigation and strength for mothers in labor. Modern bands have blended the unique songs of each island in the country with modern music. Marshall Islanders are great orators, and elaborate speeches are always given at first birthday celebrations and other public events. There is a budding song recording industry, and musical and dance performances are an important part of celebrations.