Life for any human, for any group of people, is meaningful only when one’s own decisions matter, and when one’s own choices are made in a free environment. Land issues, reparations concerns, cultural expressions, and educational reform for the CHamoru people really add up to self-determination. Without this process there can be little else.

Laura Souder-Jaffery and Robert Underwood, July 1987

In the spring of 2012, Guampedia received funding from the Guam Museum Foundation to profile the thirteen civilian Governors of Guam; the information would complement the Foundation’s portrait display in the Hall of Governors at the Latte of Freedom at Adelup.

These thirteen men represented a new phase in Guam’s political development as a territory of the United States. Prior to the 1950 Organic Act of Guam, all governors of Guam were officers appointed by the Department of the Navy. From 1898 when Guam was ceded to the US after the Spanish-American War and up to World War II, more than 30 different naval officers were assigned to rule Guam with autocratic authority. Naval rule was interrupted during the Japanese occupation of the island (1941 to 1944), but after the war, Guam returned to its previous role as a US military outpost—and the military governors returned.

The year 1950, however, marked a turning point in Guam governance. With the establishment of a civilian government and congressional US citizenship for the people of Guam through the Organic Act, the President of the United States selected the individuals, usually along party lines, who would serve as the territorial governor. Carlton Skinner was the first appointed civilian governor. In 1960, Joseph Flores, the first CHamoru governor, was appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower. Twelve years later, the first popularly elected governor, Carlos Camacho, was sworn into office.

As we discovered the stories of the civilian governors—from Skinner to Eddie Calvo—we saw that their lives and accomplishments during their administrations were set against an equally fascinating backdrop of social, political and economic change for the island of Guam. The advent of tourism in the 1960s, the growing and changing population of the 1970s and 1980s, the cycles of construction projects, the impacts on health, environment and island life, and the occasional natural disaster like Typhoons Karen, Pamela and Pongsonga, provided interesting stories of the challenges the civilian governors had to face as appointed and elected leaders.

But the story of the island’s political development that made it possible for Guam to elect its political leaders was just as compelling.

In the early years as a colony of the United States, Guam’s people endured strict governmental policies that significantly impacted aspects of culture, social life and economy, and placed strict limitations on any kind of political participation in local government. While some naval governors were sympathetic to the cause for civil rights and citizenship for the CHamoru people, they could not do much more than provide cursory gestures of support. Continual petitions by Guam leaders voicing their discontent, however, demonstrated that the CHamoru people understood their situation and the tenets and tools of democracy that could allow them to get their way, if the US government would listen and move into action.

In the post-World War II years, the rhetoric of loyalty to the US for Guam’s liberation and the island’s strategic position in the Asia-Pacific region were used to justify continued US colonization and land appropriations from CHamoru families. Nevertheless, Guam leaders sought ways to put pressure on the US government to finally organize a civilian government for Guam and grant US citizenship to its people. The Guam Congress Walkout in 1949 is often cited as the pivotal moment which led to the passage of the Organic Act because CHamoru leaders demonstrated their willingness to put it all on the line in the cause for social justice and political change.

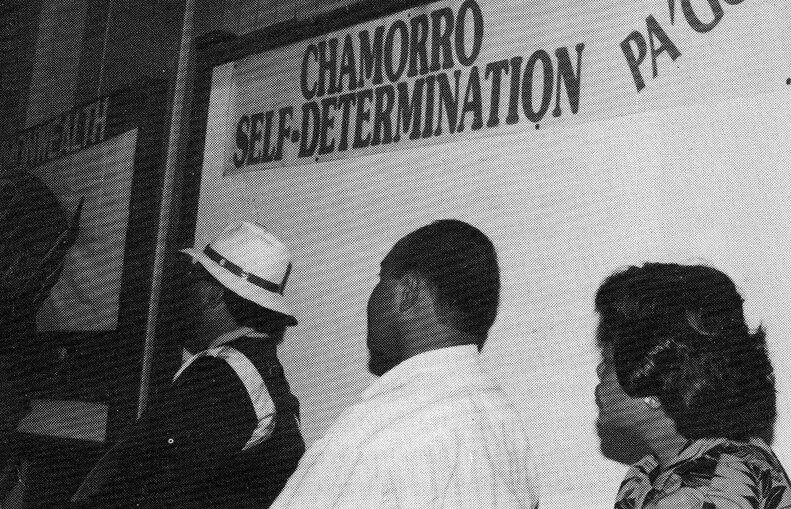

In the 1960s and 1970s, with changing attitudes worldwide against colonialism and the strongly worded United Nations’ declaration of the right to self-determination, the people of Guam began to rethink their relationship with the US and to explore what a change in political status could mean for Guam’s future. This was a time when the possibility of reunification of Guam with the Northern Marianas was explored and put aside for a later date. What followed was decades of debate and negotiations, rewrites and protests as people tried to wrap their heads around complex ideas such as self-determination, plebiscites, commonwealth status and indigenous rights. It was an exciting time in Guam’s political development that saw the emergence of CHamoru activism and the rise of a new political consciousness among the island’s people.

In the late 1960s, the first Constitutional Convention, or ConCon, was organized by the Government of Guam. The ConCon critically examined the Organic Act and recommended changes that were better suited for Guam. Around this time, Congress passed the Elective Governor Act, which paved the way for the people of Guam to elect their first governor. This was followed by another act of Congress to allow for the election of a non-voting Congressional Delegate to represent Guam in Washington, DC.

By the 1970s Guam leaders began to focus on actually changing the political relationship that Guam had with the United States. After witnessing the negotiations carried out by the islands of the Trust Territory (TTPI), especially Saipan and the Northern Marianas, Guam leaders organized the Political Status Commissions (PSC) of 1973 and 1975. The role of the PSC was to determine what kind of political status options were desired by the people of Guam. In the process they critically examined the way Guam as a possession of the US lacked political control over certain issues that affected the island, such as land issues and immigration laws. In 1978, a second ConCon was organized that actually drafted a constitution for Guam modeled after constitutions of the fifty States. However, the majority of Guam voters did not approve the draft constitution generated during the ConCon. This was partly because of the active campaigning by emergent CHamoru activist groups like PARA-PADA who were opposed to the document because it did not adequately address CHamoru rights. Some members of the PSC also believed that Guam’s political status should be determined before a constitution could be developed. It was also obvious that the US Congress wanted to maintain control over the whole process.

The Commission on Self-Determination (CSD) was created in 1980 to pick up where the Political Status Commission had left off, and began an educational campaign to teach the public about the different available political status options, as well as to conduct a plebiscite. The question of CHamoru self-determination became a major issue, especially regarding who should participate in a plebiscite that would ultimately determine Guam’s political status. As with the draft constitution, activist groups such as OPI-R advocated for the recognition of CHamoru rights to self-determination, often in opposition to non-CHamoru residents and CHamoru politicians who were uncomfortable discussing the issue of indigenous CHamoru rights. When a plebiscite in 1982 determined that commonwealth status was the preferred political status the CSD drafted a Commonwealth Act for Guam. After years of negotiation and revisions and trying to get Congress to approve it, the Commonwealth Act failed, the major reasons having to do with disagreements over immigration and the military. Nevertheless, Guam leaders organized the Commission on Decolonization to address the issue of Guam’s political status. As the organizations that preceded it, the Commission on Decolonization was tasked with assessing the desires of the people of Guam and to educate the public on the political status options of statehood, independence and free association. A decolonization registry was established for eligible voters to participate in an as of yet unscheduled plebiscite.

This convoluted narrative of the history of governance demonstrates how complicated this aspect of Guam’s past can be to grasp. With the proposed military buildup, discussions of Guam’s political status and relationship with the US—and the other Mariana Islands—have again emerged into the public’s consciousness. New activist groups have also emerged, voiced their concerns, and are trying new ways to raise awareness about indigenous rights, self-determination, and environmental and social justice. Guam’s population is larger and more diverse and more technologically savvy than previous generations. It will be interesting to see what direction the quest for CHamoru self-determination will take next.

Guam Governance and the CHamoru Quest for Self-Determination

In late 2012, Guampedia received grants from the Gannett Foundation through the Pacific Daily News and the Guam Preservation Trust to produce twenty new entries on a project generically labeled “Guam Governance.” Inspired by the desire to know more about the island’s political development Guampedia asked various writers to help put together a section that would make clear some of the major issues, challenges and accomplishments related to governance that would be useful for students and teachers of Guam history. We also wanted to remind readers of the colorful history of individuals and organizations who worked hard toward bringing political change for Guam.

The governance section builds on other sections already on Guampedia that cover politics and government. It also provides some significant historic documents, such as the Draft Commonwealth Act, the Draft Guam Constitution, and the 1974 proceedings of the Pacific Asian Studies Association seminar on political status, one of the first gatherings to discuss Guam’s political status at the University of Guam. In addition, the section features entries on the government organizations tasked specifically with dealing with complex questions of Guam’s political status, such as the Commission on Self-Determination, the Political Status Commission, the Constitutional Conventions (ConCon) and the Commission on Decolonization. Some of the activist organizations, such as PARA-PADA, Nasion Chamoru and We Are Guahan, who have been instrumental in directing the discussion of Guam’s quest for self-determination, decolonization, and issues of the impending military buildup, are also included.

Ideally, we wanted this section to provide a historical context for a new generation to appreciate the different ways CHamorus and others in our community and nation have advocated for civil rights and social justice for Guam, using the tools of democracy in the face of adversity and US efforts to exclusively control the island’s political future. There were many people involved in these efforts, from our leaders to our grassroots activist organizations. Their work should not be forgotten.

This section also would not be possible without the help of our writers, reviewers and other people knowledgable in these issues for whom we have great respect and admiration. Guampedia especially acknowledges James Viernes who helped write and review several of the entries, sometimes with little advanced notice. We also thank the many individuals who provided images and information that were vital for us to put together a comprehensive history of Guam’s quest for self-determination.

It has been a long and arduous journey to civilian government, US citizenship and elected leadership but the quest for greater self-government and self-determination for the people of Guam continues. It is our hope at Guampedia that this section will shed new light on long-standing issues, to show where we’ve been, and to encourage people to come together and talk about new ideas and ways to define, improve and achieve our island’s political aspirations.

Guampedia’s CHamoru Quest for Self-Determination entries

Overviews

- Guam’s Political Development

- Chamoru Self-Determination, An Interpretive Essay

- Self-Determination for CHamorus and Hawai’ians

Steps Forward and Back

- Civil Rights and US Citizenship (1898-1950)

- 1901 Petition

- Guam’s Strategic Value

- Partition of the Marianas

- Land Ownership on Guam

- Land Ownership on Guam, An Update

- Language Policies

- The Role of Education in the Preservation of the Indigenous Language of Guam

- The Hopkins Report

- CHamorus Yearn for Freedom, An Interpretive Essay

- National Attention on Guam’s Postwar Campaign for Citizenship

- Guam Echo and Guam Eagle

- Guam Congress Walkout

- Organic Act of Guam

- Security Clearance on Guam

- Elective Governor Act 1968

- Guam Congressional Representation Act 1972

- Guam Constitutional Conventions (ConCon)

- History of Efforts to Reunify the Mariana Islands

- Political Status Commissions

- A 1974 Analysis of Social, Cultural and Historical Factors Bearing on the Political Status of Guam

- Commission on Self-Determination

- Guam Commonwealth Act (1980s-90s)

- Commission on Decolonization

- CHamoru Registry and the Decolonization Registry

- United Nations Role in Guam’s Decolonization

- Challenge to CHamoru Self-Determination: Davis v. Guam

- Fanohge Famalåo’an and Fan’tachu Fama’lauan

People

- US Naval Era Governors: Contributions and Controversies

- Guam’s Civilian Governors

- Congressman Antonio B. Won Pat

- Congressman Ben Blaz

- Congressman Robert Underwood

- Congresswoman Madeleine Zeien Bordallo

- Speaker Carlos P. Taitano

- Speaker Francisco B. Leon Guerrero

- Sen. Vicente (ben) Cabrera Pangelinan

- Sen. Richard Flores Taitano

- Sen. Angel Leon Guerrero Santos

- Angel LG Santos, An Interpretive Essay

- Atanasio Taitano Perez

- Tony Palomo

- Laura Thompson

Organizations

- Institute of Ethnic Affairs

- OPI-R: Organization of People for Indigenous Rights

- PARA-PADA

- Nasion Chamoru

- We Are Guahan