Editor’s note: The following is a reprint, in part, from Guam History Perspectives, Volume 2, with permission from the author.

A diplomatic history 1898-1919

The Marianas archipelago was first inhabited some 3,500 years ago by people who originally came from Island Southeast Asia. Today the indigenous inhabitants are known as CHamorus/Chamorros. In 1521 Ferdinand Magellan and his crew stumbled upon these islands in his attempt to discover a western route to the Spice Islands.

The islands were colonized by Spain beginning in 1668 and renamed the Mariana Islands after Maria Ana de Austria, queen regent of Spain. Spanish colonialism provided a form of political unity for islands that already possessed a common cultural heritage but never before had been united under one government.

From the end of the Manila galleon trade in 1815 until the end of the 19th century, the Marianas colony was left to languish as an outpost of Spain’s Philippine colony.

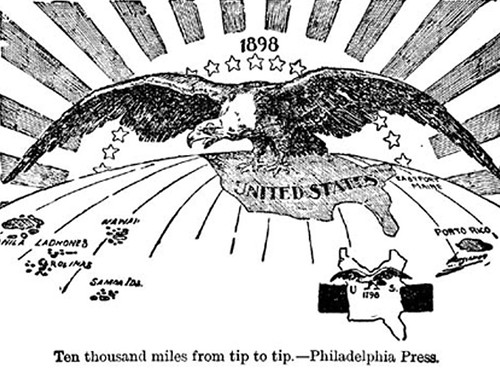

American expansionism sparked in 1887

Why, when the entire Philippine and Hawaiian archipelagoes were take by the United States in 1898, was Guam the only island taken of all the islands in the Marianas archipelago after the Spanish-American War? That question, however, must be prefaced by another: How did the United States become a Pacific colonial power in the first place?

US territorial acquisitions in the Pacific developed in connection with commercial interests in the China trade and its relation to the Hawaiian Islands. As early as 1842 the United States had announced a special interest in Hawai’i. In 1875 the US signed a reciprocity treaty with the Hawaiian kingdom, and in 1887 the renewal of the treaty included the exclusive right of the US to use the Pearl River harbor on the island of Oahu. American business interests in Hawai’i invited American annexation of the islands in 1893, which sparked the expansionist spirit of America.

Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Naval historian Alfred Thayer Mahan, among others, wrote strongly in favor of annexing Hawai’i. Their reasoning was that the move would protect both the west coast of America and the proposed Panama Canal from foreign forces.

But they were also committed to propelling America from an isolated, fledgling nation to a great world power with a global economy and a first class Navy to protect it.

President Benjamin Harrison was in favor of annexation at the time, but as a lame duck president he was unable to act. His successor, Democrat Grover Cleveland, was an anti-expansionist, and so no action was taken on annexation during his term. The issue of annexing Hawai’i became a major plank in the Republic Party platform of 1896, and following William McKinley’s inauguration as president, a new treaty of annexation was negotiated and signed on 16 June 1897. However, the US Senate was unable to garner enough support for annexation, and the issue remained in committee.

What brought about American colonial expansion in the Pacific was US opposition to the Spanish administration of Cuba. American expansionists and the yellow journalism of William Randolph Hearst’s and Joseph Pulitzer’s newspapers had been propounding the cause of American intervention because of what was portrayed as Spain’s barbaric administration of that island.

Tensions became so high between the US and Spain over Cuba that in 1895 the US Navy Department began considering plans for war against Spain. Although most Americans thought of war with Spain only in terms of Spain’s Caribbean islands, naval planners also took into consideration Spain’s Asiatic Fleet based in the Philippine Islands. Thus, the 1896 war plan written by Lt. William Warren Kimball, staff intelligence officer for the Naval War College, included an American attack on the Spanish fleet in the Philippines.

When the McKinley administration took office in the spring of 1897, Secretary of the Navy John D. Long and Assistant Secretary Theodore Roosevelt, asked the Naval War Board to reconvene and reexamine the plan of the previous administration. The board deliberated the war plan again in June 1897. Roosevelt was the ex-officio head of the Office of Naval Intelligence at the time. The Naval War College, therefore, looked to Roosevelt for advice on executive policy upon which to base its plans. Roosevelt was a staunch advocate of a strong Navy and worked diligently at preparing the US Navy for war with Spain.

He discussed his war plan with President McKinley on 20 September, toward which the president was reportedly “most kind.” In that discussion, Roosevelt outlined the necessity of defeating the Spanish fleet in the Philippines and possibly capturing Manila.

Although no specific mention of Guam is made in the war plans, the board must have been aware that reinforcements leaving San Francisco for Hawai’i and then the Philippines would necessarily have to pass near the Spanish Marianas. Sound naval strategy would require the destruction of any Spanish warships in the harbor of San Luis de Apra (referred to today as Apra harbor), Guam.

To ensure that he had an aggressive admiral in charge of the Asiatic Squadron, Roosevelt conspired with commodore George Dewey to have the latter appointed to that post. On 21 October 1897 Dewey arrived at Nagaski, took command, and was briefed on the role he was to play should war develop between the US and Spain.

At this same time Whitelaw Reid, publisher of the New York Tribune and a staunch McKinley Republican, was sent to London to represent the president at the celebration of the 60th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne. McKinley also charged Reid with the task of quietly determining whether Spain might be willing to sell Cuba to America. The answer he received from Reid was unequivocal: Spain would never sell the brightest jewel in her crown.

McKinley had not developed a cohesive foreign policy when he entered office. He had built his political base on business interests and wanted to be a businessman’s president. He did not want to have a war during his presidency, hence his business-minded effort to avoid war by attempting to buy America’s way out of the Cuban problem.

But McKinley’s hopes to avoid war were dashed when the American battleship Maine exploded at anchor in Havana Harbor on 15 February 1898. Some 260 American servicemen died.

“Remember the Maine. To Hell with Spain!” became the war cry. America’s naval leadership, especially its assistant secretary, immediately began preparations to put Kimball’s war plan, as modified by Roosevelt, into effect.

On 25 February 1898, a day when Secretary Long had decided to rest at home, Roosevelt cabled Dewey at Hong Kong:

In the event of declaration of war with Spain, your duty will be to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave the Asiatic coat, and then (begin) offensive operations in the Philippines.

On 11 April, President McKinley asked the US Congress for authority to use the military and naval forces of the US to expel Spain from Cuba. Congress adopted the war resolution early on the morning of the 20th, although officially it was the 19th. The president signed it the same day. On 24 April the president endorsed the recommendation of the Navy bureau chiefs that Dewey should attack the Philippines.

Dewey sailed into Manila Bay on 1 May 1898 and destroyed the Spanish fleet. On 4 May, after fully assessing his victory, he advised the president of the situation and requested further orders. The message did not reach Washington until 7 May.

Guam’s role in the Spanish-American War

Unofficial news of Dewey’s victory reached the US on 2 May. The message was wired from Hong Kong to British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, who passed it on to John Hay, the US ambassador to England, who immediately passed it on to McKinley. On 4 May, before official word had been received from Dewey, President McKinley approved the recommendation to send troops to begin the attack on the Spanish garrison holding Manila and to carry out his earlier verbal instructions. This decision altered the American republic fundamentally. It created the empire that exists to this day in both the western Pacific and the Caribbean.

Incredibly, McKinley did not even know where he was sending his troops. Journalist H. H. Kohlsaat visited the president at about this time and recorded McKinley’s comments:

When we received the cable from Admiral Dewey telling of the taking of the Philippines, I looked up their location on the globe. I could not have told where those darned islands were within 2,000 miles!

The Naval War Board wrote to Secretary of the Navy Long on 9 May to induce him to secure Dewey’s lines of communication to Manila by capturing Spanish Guam. Long wrote these orders to the commanding officer of the USS Charleston on 10 May, but they were sent much later. Four ships, the Charleston and three transports, left Honolulu on 4 June bound for Manila to reinforce Dewey’s position in the Philippines. Captain Henry Glass, commander of the squadron opened the orders of 10 May while under way. They instructed a stop at Guam where he was to:

use such force as may be necessary to capture the port of Guam, making prisoners of the governor and other officials and any armed force that may be there.

By 3 June, the day before Glass’s squadron left Honolulu and more than two weeks before the capture of Guam, President McKinley had decided on the minimum concessions Spain would have to make to end the war. Spain would have to evacuate Cuba and cede to the US Puerto Rico, a port in the Philippines, and an island in the Marianas.

So the decision was made then that the spoils of war would include at least one island in the Marianas, and the US never wavered from this position, which ultimately came to pass. It is probable, then, that the US would have taken Guam even if it had decided not to take the Philippines.

On 20 June, Captain Glass captured the undefended Spanish outpost of Guam. The next day he ordered the American flag to be flown and the US national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner,” to be played. The flag raising was probably the first public demonstration of America’s intention to acquire territory in the Pacific as a result of its attacks on Spanish holdings.

Leaving no troops behind as an occupying force, Glass’s squadron departed Guam for Manila on 22 June. According to the Berlin Treaty, which had been in effect since 14 June 1899, a colonial power could not lay claim to territory it did not occupy. Therefore, on 23 June, Jose Sisto, the treasurer of Guam and the only Spanish government official to escape capture by Glass, claimed the right to act as governor of the Marianas and declared that—under the Berlin Treaty—the Marianas still belonged to Spain.

The Peace Protocol

By 18 July, the Spanish government recognized that its cause was lost and asked France to help arrange for a termination of hostilities. Consequently, on 26 July a message requesting a cease-fire was delivered to the US president by the French ambassador to the United States.

Meanwhile, Admiral Mahan, who had joined McKinley’s Naval War Board upon the departure of Roosevelt, wrote to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge on 27 July that he was not comfortable with annexing the Philippines.

Might it not be a wise compromise to take only the Ladrones and Luzon; yielding to the ‘honor’ and exigencies of Spain the Carolines and the rest of the Philippines?

On 30 July, the president’s response to Spain’s request for a cease-fire was delivered to Jules Cambon, the French ambassador in Washington. Although stated more eloquently, the terms were almost the same as those in his June 3 note to Ambassador Hay. Ceding Puerto Rico and the other Spanish islands in the West Indies and one of the Marianas was considered compensation for the losses and expenses of the US during the war, and of the damages suffered by Spanish citizens during the last insurrection in Cuba. The armistice protocol incorporating this language was signed on 12 August 1898.

Interestingly, Manila was captured the day after the armistice was signed. This was not the breach of protocol that Spain made it out to be. The cease-fire message was sent from Washington at 4:30 p.m. Friday, 12 August, which in Manila was 5:30 a.m. Saturday, 13 August. It was received in Manila on the afternoon of the 16th, three days after leaving Washington.

Although the peace treaty left the political status of the newly gained islands to congress, Whitelaw Reid made clear his position on political status for the territories. In a letter to Ambassador Hay on 11 August he warned:

If we don’t insist strenuously that the territorial government is for all time, we shall be in worse danger than ever in our whole history from the demagogue who will want to make new states.

Whitelaw Reid’s position has been maintained for more than a century.

With America enthusiastic over the prospect of a military defeat of Spain, the resolution to annex Hawai’i that had been languishing in Congress since the spring of 1897 was revived. On 4 May 1898, Congress introduced a new resolution that passed in the US House of Representatives on June 15 and in the US Senate on 6 July. Hawai’i came under American control on 12 August, ironically the same day that the armistice protocol to end the war with Spain was signed.

The Naval Committee of the Senate then asked the Naval War Board to advise what coaling stations should be acquired by the United States. Mahan sent a 32-point response to Secretary Long. He said:

[I]t will be always desirable that the station ceded be an island, whose boundaries are defined by the surrounding water… [The Naval War Board] is also of the opinion that, if at all possible, any stations that may be acquired should become wholly the property of the United States, with so much of the surrounding land and water as may be needed to establish adequate protection against an enemy… The Island of Guam, before mentioned, one of the Ladrone Islands, is comparatively small, being about thirty miles in length, with an excellent harbor, a little less than 1,500 miles from Manila, and 3,500 miles from Hawai’i…As it is observed that by the protocol lately signed between the United States and Spain, the former is to “select” one of the Ladrones, and as the Board is not fully informed as to the precise character of the harbors in the other islands of the group, it is recommended that before a “selection” is made, one of our cruisers should be sent to the Ladrones to examine the different harbors and to recommend the most suitable one.

Mahan said that a coaling station at Guam, with others at Samoa, Luzon and Hawai’i:

would largely meet the needs of the US for naval stations, both for transit to China and for operations of war…; for naval stations, being points for attack and defense, should not be multiplied beyond the strictly necessary.

Here it seems that the man who had become famous for his 1890 treatise on the influence of sea power, the need for a big Navy, and the larger policy for America was becoming fainthearted. Reluctant at first to take all of the Philippines and willing to settle for Luzon and the Marianas, a month later Mahan was willing to settle for just one island in the Marianas. Mahan contradicted himself by initially holding that the surrounding land and water should be taken to provide adequate protection from an enemy and then suggesting that only one island should be taken. It is impossible for one island in the Marianas to be protected from an enemy dwelling on another island a mere sixty-four kilometers (forty miles) away. By not advising that the US should take all of the Marianas, if it was going to take any, Mahan cost America dearly in 1941.

Part of the answer to why only Guam was taken, therefore, is that there was no pressing military need for the rest of the Marianas. Mahan, America’s leading naval historian of the time and supposedly America’s leading naval strategist, advised against taking any more islands than were absolutely necessary. In his opinion, only Guam was needed, and in the end only Guam was taken.

Was only Guam captured, or all of the Marianas?

When the treaty ending the Spanish-American War was finally signed on 10 December 1898, the US had gained Guam, Puerto Rico, and all of the Philippine Islands. Thus the US became a colonial power in the Pacific. But the key question remains: Why only Guam—why not all of the Marianas?

The answer is not necessarily that this was the recommendation of Mahan and the Naval War Board because, as events developed, there were several opportunities for the acquisition of the Marianas between the time of the Naval War Board’s recommendation and the signing of the Treaty of Paris. The answer entails other questions: Did the US have the option to take all of the Mariana Islands? And did the US capture all of the Marianas or only the island of Guam?

Capt. Glass’s orders of 10 May, as they appear in the 1898 congressional documents, are not titled “Seizure of Guam,” but “Seizure of the Ladrone Islands.” But Glass’s orders specified the capture only of Guam, and Glass’s letter to then-Spanish Governor Marina demanded the surrender only of Guam.

Rear Admiral Stephen B. Luce advised Senator Lodge, also on 10 May, that the islands should be taken in their entirety. He said that arbitration between Spain and Germany had already determined that the Carolines were part of the Philippines. Therefore, the Carolines would go to the US if the Philippines did, and the same would hold true for the Marianas. Lodge responded in agreement on 12 May.

Journalist William M. Laffan of the New York Sun visited President McKinley in July and subsequently advised Lodge that the president was considering taking control of the Philippines, the Marianas and the Carolines first, and deciding later what should be kept. Similarly, Lodge wrote to Roosevelt on 12 July, pleased that the president had taken the initiative to acquire the Marianas.

Lodge advised against taking only one island in the Marianas group, which he said would open the door to many troubles. Because Germany, the European power most critical of American foreign policy, was casting longing looks at the Marianas, Lodge held that the US would not want Germany so near.

When Lodge wrote his account of the Spanish-American War, and specifically about the capture of Guam in the Marianas, he spoke of the conquest of “those remote islands, which were henceforth to know new masters.”

During his interview with French Ambassador Cambon on 3 August, which eventually led to the signing of the peace protocol, President McKinley suggested that all of the Marianas might be taken. The president said that the question of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the other West India islands in the Ladrones, admitted no negotiation.

While the negotiations were going on, the peace commission conducted several hearings in Paris. Major General F. V. Greene, as noted in the Treaty of Peace 1899, reminded the peace commissioners of the political status of the islands:

The government of the Philippine Islands, including the Ladrones, Carolines and Palaos [Palau], is vested in the Governor-General, who, in the language of the Spanish Official Guide or Blue Book, is the sole and legitimate representative in these islands of the supreme power of the Government of the King of Spain.

Others also thought the entire Marianas chain had been taken. Representative E. D. Crumpacker told the House of Representatives on 25 January 1899:

We have added to the national domain the Hawaiian Islands, Porto Rico (sic), the Philippines and the Ladrones.

At least certain German observers also expected the Americans to take all of the Marianas. According to the Deutsche Warte, 20 August 1898:

The United States has annexed Hawai’i, and as spoils of the war, the Ladrone Islands, with a coaling station in Guam Island, have fallen to her share.

Peace Commissioner William P. Frye thought all of the Marianas were in American control. He said during a commission meeting:

We hold Porto Rico (sic) and the other islands in the West Indies and the Ladrones as an indemnity in lieu of money.

Commissioner Frye questioned Commander Royal B. Bradford, chief of the Bureau of Equipment and US Navy adviser to the commission, about the Navy’s contention that all of Luzon in the Philippines was in the military possession of the US when only Manila had actually been captured. Bradford responded:

Simply because we have captured the seat of government and practically all of the Spanish forces.

Commissioners Frye, Cushman K. Davis, and Whitelaw Reid came to agree with Bradford. They wrote to the Secretary of State on 25 October:

Spain governed these Islands [the Philippines] from Manila; and with the destruction of her fleet and the surrender of her army we became as complete masters of the whole group as she had been… The Ladrones and Carolines were also governed from the same capital by the same Governor-General.

This line of reasoning regarding the extent of the captured territory proved sufficient for America to gain ownership of the entire Philippine archipelago. It would have also been sufficient for America to gain ownership of the rest of the Marianas and Carolines.

Treaty negotiations and the Germans

Records of the negotiations that resulted in the Treaty of Paris and the end of the Spanish-American War indicate that one of the reasons all of the Mariana Islands were not taken by the US was that in 1898, America was still a neophyte at international diplomacy. But Germany had a vested interest in the Philippines and Asia, and German diplomats developed and maintained a firm and unified position and achieved their desired goals.

The negotiations began in Paris on 1 October 1898, with the introduction of American and Spanish commissioners. President McKinley chose his five commissioners expertly:

- Whitelaw Reid, a Republican and an avowed expansionist, was the owner and editor of the New York Tribune.

- Senator Cushman K. Davis, chair of the Foreign Relations Committee and Senator William P. Frye, both Republicans, were also expansionists.

- Senator George Gray, the only Democrat among the five, was an anti-expansionist.

- William R. Day, who stepped down from his post as US Secretary of State to head the delegation, favored taking only the island of Luzon and a string of smaller islands, including Guam, that would provide the US with stepping stones to the Asian marketplace.

At the second conference it was agreed that the protocol of August 12 would be the basis of negotiation. Significantly, the protocol did not call for the cession of the Philippines to the United States: instead, it stipulated only that:

the United States is entitled to occupy and will hold the city, bay and harbor of Manila pending the conclusion of a treaty of peace.

Similarly the protocol identified only an island in the Ladrones, to be selected by the US.

This language did not preclude the US from taking all of the Marianas or all of the Philippines.

On 14 October, US Commander Bradford emphatically expressed his opinion regarding the acquisition of all of the Marianas. He recommended taking not only all of the Marianas but also all of the Carolines. He used the annexation of Hawai’i as an example:

Suppose we had but one, and the others were possessed of excellent harbors… Suppose also the others were in the hands of a commercial rival, with a different form of government and not over[ly] friendly. Under these circumstances we should lose all of the advantages of isolation.

After an extensive tour of the US, McKinley reached a decision: He would demand all of the Philippines. On October 26, three days after Frye, Reid, and Davis recommended taking all of the Spanish holdings in the western Pacific, including the Philippines, the Eastern and Western Carolines and the Marianas, McKinley had Secretary of State John Hay send a two-paragraph message to the peace commissioners in Paris. The first reiterated America’s claim to conquest of the islands. The second paragraph said:

Consequently, grave as are the responsibilities and unforeseen as are the difficulties which are before us, the President can see but one plan path of duty—the acceptance of the Philippine archipelago.

What happened to the Marianas? Almost every expert who had been asked had said that the Marianas were part of the Philippines and had recommended that they be taken. All of the Philippines were taken, purportedly because separating them could not be justified on political, commercial or humanitarian grounds.

Apparently then, either the president was merely biding his time on the issue of the Carolines and the Marianas, as he had done on the Philippines, or somewhere within the political, commercial, or humanitarian arenas, partitioning the Marianas could be justified. But where?

The answer comes from the files of the German foreign office.

Historically, Germany had become an imperialist power in 1884 with its annexation of New Guinea. In that same year the German-Spanish rivalry over the Carolines began. Spain put forward a claim on the basis of discovery. Germany’s Bismarck government thought that the Carolines were not worth a conflict. To save face, Bismarck suggested arbitration by Pope Leo XIII who predictably adjudicated the Carolines to Spain in 1885. Spain was to obtain (or maintain) sovereignty over the Carolines, but German traders would have free access to the Islands. Germany was given control of the Marshall Islands.

In 1889 the US and Germany nearly came to blows over the question of the partition of Samoa. In 1897 the German parliament approved a five-year building program that would give Germany a fleet of 19 battleships. In November 1897 Germany occupied Kiaochow By in Shantung, China and subsequently received a 99-year lease on the bay in addition to military and railway privileges. By the time of the outbreak of hostilities between America and Spain, Germany was also in control of the Bismarck Archipelago to the northeast of New Guinea.

On 11 May 1898, ten days after Dewey had sunk the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay, Prince Henry of Prussia, brother of Kaiser Wilhelm II, telegraphed from Hong Kong to Bernhard von Bulow, German foreign affairs secretary:

A German merchant from Naila has stated in a way most worthy of credence that a rebellion has justified itself in the Philippines and will succeed; that the natives would gladly place themselves under the protection of a European power, especially Germany.

He said there were three possibilities for the Philippines:

- a protectorate, possibly under Germany

- the division of the island group between European powers, in which case Germany would naturally acquire her share or

- the neutralization of the Philippines under the guarantee of the powers.

Most European leaders did not believe that the US would ever assume control over all of the Philippines and were shocked when it did. It is not surprising, therefore, that Germany showed interest in the Philippines when it became apparent that they might be available for acquisition.

On 2 June, the German Kaiser ordered a large naval squadron to Manila in order to form an opinion on the Spanish situation, the mood of the natives, and foreign influence upon the political changes. Its commander, Vice-Admiral Otto von Diederichs, the German naval officer who had successfully forced German interests into Kiaochow the year before, made things unpleasant for Dewey by steaming around the bay in apparent disregard of the American siege. News of von Diederichs’ actions generated considerable anti-German sentiment in the US.

On 9 July American Ambassador to Berlin Andrew Dickson White, a Democrat and anti-imperialist, met with German Undersecretary of State Oswald von Richthofen, who told Ambassador White that “the acquisition of Samoa [as compensation for Hawai’i] and of the Carolines [as satisfaction of national pride after the papal adjudication of 1885] would be desired for Germany; furthermore one or two positions in the Philippine group and the Sulu Archipelago would be wanted.”

White, in turn, dropped an unauthorized hint that the US would most likely not want to keep any of the western Pacific islands. He told von Richthofen that, in his opinion, the US would want to keep no more than a coaling station or two.

Ambassador White cabled Secretary of State Day on July 12 that the US should be “friendly to German aspirations” to assure Germany’s friendly cooperation. On the 13th, White telegraphed Day that he had again met with a representative of the German government (presumably von Richthofen) to discuss the Philippine situation. White said he (White):

also referred to the Ladrone Islands and to the reports of their capture by our transports, as an incident in their voyage to Manila, and asked [von Richthofen] in a jocose sort of way whether Germany would have any use for them. [Von Richthofen] seemed to think the matter well worthy of consideration.

White also telegraphed Day that assurances as far as our government can see its way to give them may save the US later troublesome complications.

Thus Ambassador White, without any direction from Washington, was willing to give to Germany practically everything America had captured. When these messages were relayed to President McKinley, he expressed surprise and warned White to be more reserved in his conversations. Nevertheless, no doubt could have been left either in the president’s mind that Germany was seriously interested in the fate of Spain’s Pacific colonies or in the Kaiser’s mind that America had yet to formulate a unified position on what to do with its newly captured territories.

German representatives also approached Ambassador Hay in London. On July 14 he telegraphed to Secretary Day that Germany desired very little. They wanted a few coaling stations, and hoped that in the final disposition of the Philippines, that might be arranged.

On 27 July, after a personal visit from Count Paul von Hatzfeldt-Wildenburg, the German ambassador in London, Hay expressed his true sentiments to Lodge:

[T]he Vaterland [Germany] is all on fire with greed, and terror of us. They want the Philippines, the Carolines, and Samoa—they want to get into our markets and keep us out of theirs…There is to the German mind, something monstrous in the thought that a war should take place anywhere and they not profit by it.

When the peace protocol was signed on 12 August, Germany realized that attempting to deal directly with the United States would be fruitless. The next day the German foreign office in Madrid was asked to find out what Spain would accept for the purchase of Kosrae, Pohnpei, and Yap. Although no price was settled on, a secret agreement was reached on 10 September 1898, whereby Spain promised Germany preemptive rights to Kosrae, Pohnpei, and Yap upon the conclusion of peace. Arrangements could also be made for whatever else the US did not take and Germany might want. The US suspected Germany’s covetousness—as previously noted, Bradford had predicted that Germany would purchase any Spanish-held islands not obtained by the US.

Three of the five American peace commissioners, Reid, Davis and Frye, advised President McKinley by telegram that any territory not taken by the US would fall into the hands of hostile competitors. The president had already prepared a telegram, dated 26 October, that advised the American commissioners of his decision to take all of the Philippines. Probably as a result of the commissioners’ 25 October telegram, however, the president hesitated, reconsidered, and then telegraphed his decision to the commissioners on 28 October. In it the president reiterated his decision to acquire the Philippines, but he made no mention of the Carolines or the Marianas, leaving the question open in the minds of the peace commissioners.

On 10 November, Whitelaw Reid said the US would be willing to give Spain US$12 million to US$15 million for all of the Philippines, Carolines, and Marianas. The response to the possible acquisition of the Carolines, Marianas and Philippines arrived from Washington on 14 November. The president still insisted on the retention of all of the Philippines and wanted an effort made to acquire the most eastern of the Carolines, meaning Kosrae. American business interests wanted a cable station there to link Hawai’i to Guam and Asia, and American Protestant missionaries based in Boston wanted to maintain their half-century old mission on the island. Again, neither the Marianas not the rest of the Carolines were mentioned. It is clear, then, that there were neither economic nor religious reasons strong enough to compel the president to show interest in the rest of the Marianas.

The message from the secretary of state also suggested that either Commissioner Day or the secretary of the commission, John Basset Moore, had made some sort of commitment to the German ambassador in Washington that might interfere with the acquisition of Kosrae. This was to be only the first mention of possible collusion between the American peace commissioners and representatives of the German government.

On 15 November the American commissioners prepared an ultimatum to be presented to the Spanish commissioners: either accept the cession of the Philippines or move for adjournment and return to war. The Americans offered the full US$20 million authorized by the president but did not demand any islands other than the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Although Davis, Frye, and Reid argued for the inclusion of Kosrae, they finally agreed to a phrase suggested by Day that left that island’s future open to discussion after Spain agreed to relinquish the Philippines.

A key figure in the negotiations was George Herbert Munster, Germany’s ambassador to France. He had been living in Paris for 13 years prior to the Spanish-American War and was well known in diplomatic circles. When the American commissioners arrived in Paris for the peace negotiations, the Kaiser telegraphed Munster to make a point of seeing Whitelaw Reid every day. Munster and Reid had known each other since 1889, and “when their friendship was renewed they had frequent opportunities for talk.”

On 15 November, the same day that the Americans had prepared their ultimatum for the acquisition of all the Philippines, Munster dined with the American peace commissioners, and afterwards they discussed their positions. The Americans said they were going to ask only for Kosrae in the Carolines. That night Munster informed the foreign office in Berlin that the Americans had agreed as far as the other islands (Pohnpei and Yap) are concerned, to respect the arrangements between Spain and Germany. This statement is significant because it implies that Munster had revealed the secret Spanish-German agreement and had received some commitment from the peace commissioners. Munster probably did not reveal too much, though, as indicated by later developments.

On 21 and 22 November Munster was directed to dissuade the Americans from taking any other islands and to inform them that Kosrae in Particular lay within Germany’s sphere of influence. To accomplish this Munster turned his attention to his friend Whitelaw Reid. When Munster repeated Germany’s claim that Kosrae was within the sphere of influence of the German Marshall Islands, Reid pulled out a map and showed Munster that Kosrae was far to the southwest of the Marshall’s and was rightly part of the Carolines. It appeared that Munster was now renewing Germany’s 1885 claim to the Carolines. Reid then told Munster that he thought Germany was interested not only in Kosrae but also all of the Caroline Islands. Munster parried:

I agree with you precisely; and I tell you these Colonial Department people are all alike—all savages, who can’t eat without gorging—not civilized sufficiently to know when they have had enough, and unable to resist the sight of raw meat! They are tiresome, these colonials.

Munster informed Reid that if America did not interfere with Germany’s acquisition of the Carolines, the Palau Islands and the Marianas with the exception of Guam, then Germany would waive any claim to the Sulus in return for a coaling station on one of them.

Munster spoke with Reid again on 25 November, continuing his effort to sway the American away from Kosrae. But Reid stood his ground and told him that if the Spaniards accepted the ultimatum for the Philippines, the Americans would proceed with attempting to gain control of Kosrae. Munster then told Reid that it would be best if he telegraphed Reid’s position to Berlin and left the problem for the German foreign office to settle in Madrid or Washington.

If Whitelaw Reid’s diary can be believed, as of 25 November Reid still did not know the nature of the secret agreement between Germany and Spain because he wrote after that 25 November meeting with Munster:

The impression left distinctly upon my mind…was that his government was jealous of our proposed acquisition…and was probably anxious of…in some way laying claim to the Carolines.

On Sunday, 27 November, John B. Jackson, the American charge d’affaires in Berlin, was asked to call at the German foreign office and was met by Baron von Richthofen. There Jackson was presented with a copy of Munster’s telegram stating what Reid had told Munster of the American demand for Kosrae. Jackson was also shown instructions that had been sent to Baron Speck von Sternburg, the German charge d’affaires in Washington, regarding Munster’s report of his conversation with Reid. In addition, von Richthofen referred to his own conversations with Ambassador White in the previous July. Baron von Richthofen pressed the points that the German public felt that Kosrae lay within its sphere of influence and that if the US took it, Germany would probably do nothing untoward, but that lasting friction would develop between the two countries.

Jackson then asked von Richthofen if Germany was negotiating with Spain for the Carolines. Von Richthofen replied that he knew Germany was ready to acquire them at any time, but that no negotiations were taking place. What von Richthofen omitted saying was that Germany had already made a deal and was trying not only to protect it but also to enhance it.

Von Richthofen then suggested that if the US would forget about Kosrae, Germany would not oppose an American taking of another island in the Marianas. The door to the Marianas was opened again but quickly shut. In his telegram to Washington reporting on the conversation, Jackson advised that Germany would not in any way oppose the taking by the US of another of the Ladrones in the place of one of the Carolines. But at the end he added:

My personal opinion is that German public opinion is so sensitive about the Carolines that the German Government might be willing to negotiate exchanging the most northern of the Marshall Islands as a cable station if we persist in taking Kosrae from Spain.

This long telegram from Jackson to Secretary of State Hay was received and translated for the president at 3 pm on 27 November.

As Jackson suspected, this same diplomatic scenario was being repeated in Washington between Speck von Sternburg and Secretary of State Hay. On Monday morning, 28 November, von Sternburg told Hay that the American possession of Kosrae would be “for America without importance, but for Germany a thorn in the flesh.”

Hay took it to the president, who must have already seen the message from Jackson. On 30 November Hay reported to von Sternburg that the US had no desire to disturb its friendly relations with Germany and would consider another island for a cable station, possibly in the Marshall’s.

On 28 November in Paris, Spain had reluctantly accepted the ultimatum regarding the Philippines. The American commissioners, unaware of the president’s decision, proceeded with their plan to acquire Kosrae. On November 30 the commissioners offered to pay US$1 million for Kosrae in addition to the US$20 million for the Philippines, should Spain agree to the sale. Spain declined.

The next day, 1 December, the peace commissioners received a dispatch from Washington dated November 30 to the effect that the Germans were objecting strenuously to the US acquisition of Kosrae. This was in response to Jackson’s message and von Sternburg’s visit to Hay. According to Hay, the Germans claimed to have received assurances from the American commissioners that nothing would be done to interfere with German rights and interests. Hay said:

The President is not aware of such assurances, but wishes you to be governed by them, if they have been given.

Bernhard von Bulow later reported that the:

American peace delegates in Paris declared to our ambassador there (Munster) that, in accordance with special instructions from President McKinley, the American government had decided to respect the secret negotiations in September between Germany and Spain.

Again it seems that the American peace commissioners had been made aware of Germany’s secret arrangement with Spain and that the American delegation agreed that they would not interfere with that agreement. This contention is supported by reports from both Munster and von Bulow.

The Spaniards apparently believed that the ultimatum they had accepted on November 28 was binding; the US would take only the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific, thereby allowing the Spanish government to be free to negotiate the disposition of the rest of its island holdings. On 2 December the Spanish minister of state’s offer to sell to Germany the rest of the Carolines, besides Kosrae, Pohnpei, and yap, was readily accepted. When Germany expressed interest in the Marianas (excluding Guam), Spain also offered the Palau Islands.

The same day Spain offered a deal to the American peace commissioners. In return for an “open door” concession to Spain in Puerto Rico and Cuba, the same as had been provided for them in the Philippines, Spain would cede all of the Carolines and the Marianas to America. For the first time all five American commissioners agreed on the complete acquisition, as long as the door was restricted to only five years, and sent that suggestion to Washington. The response arrived on the morning of Sunday, December 4:

The President is still of the opinion that preferential privileges to Spain in Puerto Rico and Cuba are not desirable. He would even prefer that (a) treaty should be made on (the) basis of ultimatum rather than risk the embarrassments which might result form such concessions.

Historian Wayne Morgan has expressed the opinion that this meant the president did not want to risk the embarrassment of a protest in Congress from “tariff protectionists and jingoes” during the treaty ratification hearings should such a concession be granted. This proved to be America’s last chance to gain control of all of the Marianas as a result of the Spanish-American War. On 10 December the peace treaty between the US and Spain was signed, with only Guam among the Marianas going to America.

Spain accepted in principle the German deal for the Carolines, the Palau Islands, and the Marianas (except Guam) on 5 December. Negotiations continued until 20 December when an agreement amending the 10 September arrangement was reached.

The treaty between Germany and Spain could not yet be completed, however, because the question of Kosrae remained unresolved. That issue came to rest after 17 January 1899, when Commander E. D. Taussig, captain of the US gunboat Bennington, laid claim to Wake Island. Germany decided not to contest the issue, and the American effort to gain control of Kosrae was dropped.

The question of the Marianas, however, was still not fully resolved. In January 1899, Germany, concerned about the high price Spain was asking, considered taking only the Carolines. Germany even asked Japanese Foreign Minister Shūzō Aoki if Japan would be interested in buying the Marianas. But then Spain compromised, and Germany, without ever having participated in the war, concluded its negotiations with Spain on 10 February 1899, agreeing to pay 25 million pesetas (16,750,000 marks or US$4,200,000) for the Carolines, the Palau Islands, and the Mariana Islands (except Guam).

The Kaiser was so pleased with the successes of his foreign office that he rewarded von Bulow with the title of count. Munster received the title of prince for his efforts.

Senate opposition

One last event had to occur before the American acquisition of the newly conquered territories could be completed. The treaty to end the Spanish-American War had to be ratified by the US Senate. Stiff opposition came from anti-expansionists, primarily Democrats, who argued that the American republic had neither the right nor the authority to acquire lands that lacked any foreseeable chance of becoming fully integrated states.

As the Senate vote loomed, the expansionists did not have the two-thirds majority necessary for ratification. At the last moment, William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic Party presidential hopeful, arrived on the scene and convinced several of his supporters, who were anti-expansionists, to vote for ratification and allow the expansionists to have their day. He said that during the next election they would then campaign against the Republicans and their imperialistic mode.

On 6 February 1899, with these few extra votes in hand, the Senate voted 57 to 27 in favor of ratification of the Treaty of Peace to end the Spanish-American War. The margin was a mere one vote over a two-thirds majority.

Thus, without the self-motivated political gamesmanship of William Jennings Bryan, the US Senate would have defeated the treaty and the US would not have gained possession of the Philippines, Guam or Puerto Rico. The Marianas would not have been partitioned. But the Rubicon had been crossed, and the United States of America became the last nation to join the family of imperialists. Bryan’s hypocrisy was widely recognized. He lost the 1990 election to McKinley by an even larger margin than in their 1896 contest.

Outcomes

Germany eventually established district offices at Saipan, Yap, and Pohnpei. While the new American naval government taught the CHamorus in Guam the English language and the rudiments of American political principles, the Germans taught the CHamorus and Carolines in the northern Marianas the German language and work ethics.

Professor Gerd Hadach, who has written extensively on the subject of the German Marianas, states:

The background for the acquisition was national prestige in the age of imperialism. Emperor Wilhelm took a personal interest in the Navy and colonial expansion, and if any colonies were for sale, the German government would be a potential buyer. It is obvious from the German records that the German government, and possibly the Spanish government, always assumed that the armistice was final, and that the US (was) only interested in Guam. If the US government had changed (its) mind and claimed all of the Marianas, the German government would certainly have acquiesced, as they did not have a strong motive.

Why, then, did the US not take all of the Marianas instead of only Guam? The answer is complex: in part because there was no pressing military need, in part because there were no perceived economic advantages, and in part because too often the right hand (the peace commission) did not know what the left hand (the president, his ambassador, and the secretary of state) was doing. And most assuredly the US did not take all of the Marianas because Germany wanted them and, being experienced in negotiating, maneuvered for them and was prepared to pay for them. To paraphrase McKinley’s justification for acquiring all of the Philippines, there were neither military, economic, nor humanitarian reasons strong enough to compel America to acquire the Marianas in their entirety.

As with all national policy decisions, the responsibility for the decision on the partition of the Marianas rests ultimately with the president. Despite the blundering of Ambassador Andrew White in Germany, despite possible indiscretions by Day or Moore with the German ambassador in Washington, despite all the machinations of the German foreign ministry in Paris, the final decision was made by McKinley upon Spain’s last desperate effort to regain some financial advantage from its lost colonies in the Caribbean and the Pacific.

The president was more concerned about Senate ratification of the treaty than the effect the treaty would have on the island people. The debate between expansionists and anti-expansionists was fierce. It is probable that the president, in conference first with Secretary of State Day in June and then in October and December with Secretary of State Hay, was satisfied to take what had been gained in their “splendid little war” with Spain and hoped their friends in the Senate could get the treaty ratified.

In hindsight, however, had McKinley claimed the Marianas early on, perhaps as part of the armistice protocol, the treaty debate would have been no different and America would have stood on much firmer ground in 1919 and 1941. For with the Marianas in American hands, the US could have given up the Eastern and Western Carolines to the Japanese in 1919 without jeopardizing the security of the strategic naval base at Guam in the Marianas. And with the Marianas fully fortified in 1941, Japan might instead have turned its martial spirit toward its traditional enemy, Russia.

View images in Flickr here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/guampedia/sets/72157622402562355.

By Don Farrell

For further reading

Farrell, Don A. “The Partition of the Marianas: A Diplomatic History, 1898-1919.” ISLA: A Journal of Micronesian Studies 2, no. 2 (1994): 273-301.

–––. The Pictorial History of Guam: The Americanization 1898-1918. 2nd ed. Tamuning: Micronesian Productions, 1986.

Fritz, Georg. The Chamorro: A History and Ethnography of the Marianas. Translated by Elfriede Craddock and edited by Scott Russell. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1986.

Lodge, Henry C. The War with Spain. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1899.

Pratt, Julius W. America’s Colonial Experiment: How the United States Gained, Governed, and in Part Gave Away a Colonial Empire. New York: Prentice-Hall, 1951.

Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. “Treaty of Peace between the United States and Spain: December 10, 1898.” http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/sp1898.asp