Micronesia Pathway

Table of Contents

Introducing Guampedia's Micronesian Milestones

A Journey of 4,000 Years

Pacific Islander historians and scholars have long called for a view of our pasts, not as static linear timelines that move in one direction from the past to the present, but as fluid cycles in which the past, present, and future are interdependent on each other, entangled in infinite trajectories that are forever a part of our Islander worldviews. Still, many historians continue to insist on the absolute centrality of the dates, names, events, places, and other particulars of the past that make up clear, convenient, and neatly organized chronologies that have led us to where we are today.

Guampedia’s Micronesian Milestones – A Journey of 4,000 Years offers us a valuable resource that makes notable strides in bridging the gap between these seemingly divergent and antagonistic ways of doing and knowing the past.

The Micronesian Milestones timeline, at first glance, appears to be yet another linear accounting of history like so many others. It has a defined starting point of 2,500 BC, though no clear point of conclusion as historic events will be added as they occur. Events appear in chronological order. For the most part, these events appear to be unchangeable fixtures of the past. As one scrolls through the timeline, s/he engages in a cascade of people, places, and events plotted tidily on to what seems a set course through space and time.

But Micronesian Milestones diverges from traditional timelines in a number of ways. Most prominently, the timeline places Micronesian history not in isolation, but alongside major milestones in world history. This proves a significant departure from the practices of many historians who often create tunnel visions of the past, focusing only on specific places, peoples, and time periods.

Indeed, the range of historical players on this timeline far exceeds that of any single, Micronesia-focused historical resource to date, and these players demonstrate an immense breadth of heroic triumphs. They range from the ancient settlements of Micronesian islands by seafaring peoples, through the survival of world wars and epidemics, to the election of the first indigenous woman elected as the head of an independent Pacific Island nation in the 21st century.

This broader view of Micronesian pasts within a larger global history is complemented by a calculated effort to position Micronesia and Micronesians, not as simple bystanders of the larger more prominent histories of Euro-American and Eastern world powers, but rather, as central players and active historical agents in their own pasts. Unlike many textbooks and other “traditional” historical records that often position Micronesia as a place where history happens to Micronesians, this timeline clearly situates our islands and their peoples as bona fide actors that make history happen in and beyond their islands.

In addition to highlighting Micronesian historical agency and advocating for the parity (if not preeminence) of Micronesia’s pasts alongside those of the greater world beyond the region, the Micronesian Milestones timeline departs from most textbook histories of the region in its attempt to diversify the usual suspects of historical narratives. While widely renowned political leaders, educators, and other elite actors and the major events they are linked to are placed within the historical narrative, the timeline likewise features everyday women and men who have made history in their own epic ways – histories played out in diverse settings ranging from villages and atolls, to the hallways of the United Nations, lavish dinner parties of high European society, and foreign vessels on the high seas. Indeed, this timeline offers us intimate encounters with what Chamorro historian Anne Perez Hattori has characterized as “seemingly ordinary people with extraordinary stories to tell.”

Regardless of the events or names that appear on this timeline, whether great or small, each entry offers readers with useful context and content through which they might more deeply engage the past. By no means are the entries an exhaustive narrative of particular events or individual stories. But, unlike many other timelines, Micronesian Milestones contains entries that transcend mere plots on a storyless line – entries that beckon further and deeper exploration. Paired with this context and content, readers of the timeline enjoy a rich collection of meticulously collected images that help us to visualize the past, enticing us to more intimately connect with it, and perhaps, see ourselves and our islands within it.

The Micronesian Milestones timeline is a work in progress. It is not meant to serve as a complete history of Micronesia, for there will never truly be one. There is still, and always will be, more to come. Embracing the endless possibilities of technology, Guampedia has provided a starting point for engaging our Micronesian pasts in a way that does not become stagnant or fixed, but rather, a way is open to additions, revisions, and endless innovations. Developed primarily by Guam-based and Chamorro history focused professionals, this timeline begs for far more stories and amplified voices from other Micronesians beyond Guam’s shores. Guampedia continues its efforts to reach out to the region, inviting additions to this timeline by elders, arm chair historians, professionals, and others across Micronesia.

Named Micronesia, or the “tiny islands,” the peoples and places across this subregion of Oceania continue to dismantle this misnomer. There is nothing tiny about our pasts, nothing tiny about the worlds that we inhabit and navigate within and beyond. What rich stories of our not- so-tiny “tiny islands,” then, wait to be told and shared? How will these stories lend to our ever- growing love for our islands and our understandings of their rich and complex pasts? It is our collective responsibility to ensure that we create a space for these stories to grow and thrive. The Micronesian Milestones timeline is but one venue for this to happen, and it is with great pride that Guampedia provides an opportunity for the community engage deeply and meaningfully with their collective Micronesian pasts.

The Archaeological Evidence

The Guampedia Timeline offers a reference for navigating through the history of the last years, decades, centuries, or longer. Any question about cultural history can be explored through this timeline.

Concerning the most ancient history and archaeological periods, large blocks of time have been less detailed than the numerous points appearing later in the timeline. The amount of historical information has been increasing with every passing year. Recent history has been chronicled while it happened, through written records, news reports, government documents, and more. By comparison, less documentation occurred some decades ago, and even less had occurred centuries ago.

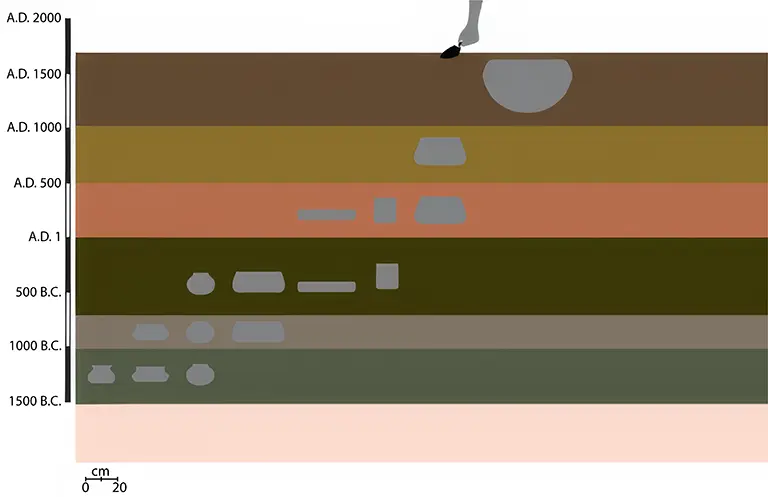

During the most ancient time periods, the people of Guam and the larger Pacific Oceanic region did not maintain written histories. Instead, their legacies have survived in language and other cultural traditions. Additional facts about ancient times have been revealed through the durable artifacts in archaeological sites and in layers beneath the ground.

The older archaeological periods do not refer to pinpointed events in historical calendars, but they can outline large blocks of time. Each block extends over a few hundred years. Specific historical events have not been recorded in the same ways of later written histories. Rather, archaeological layers contain broken pieces of pottery, shell and stone tools, diverse shell beads and ornaments, remains of shellfish and other food debris, traces of housing posts, fireplaces, and other remnants of the ancient past.

Working with the material archaeological layers as the basic building blocks of a timeline, each block included a number of centuries. Archaeological layers accumulated over long periods, necessarily encompassing many years. Inside each layer, radiocarbon dating and other evidence can point to the general age range, always bracketed within a span of a number of centuries.

Each archaeological “block of time” can be defined by its collective set of artifacts and other material findings. This collective scope encompasses the diversity of the individual people and events that comprised the reality of ancient history. Specific historical events of course transpired, but their results have survived in the archaeological record among the broader assemblages of artifacts of their general time periods.

Archaeological records can portray general views of what people did in different geographic places and during large blocks of time. The evidence consists of the material remains of ancient life, such as in the forms of the tools that people used, the foods that they ate, and the houses that they occupied. In certain cases, the evidence can be interpreted in terms of social events and contexts, such as at sites related with initial island settlement, ritual ceremonies in caves, or other specially defined circumstances. Overall, though, the physical evidence has generated pictures of the generalities of daily life in the places of particular archaeological sites and during the measured blocks of time.

When archaeological blocks of time are arranged in their proper chronological order, then they can fit into a sequence, such as in the Guampedia Timeline. As shown here, the archaeological evidence has revealed the timing of when ancient people first were living in an island group or archipelago, when they produced different styles of pottery or other artifacts, and when they constructed certain traditions of stone monuments. Beyond these major points of interest for a timeline, the complete archaeological records include much more information, just like the historical records of later years involve much more than can be condensed into a single timeline.

As depicted in the Guampedia Timeline, the archaeological evidence so far has highlighted a number of events over the course of thousands of years of ancient history. The material record started with the deepest and oldest archaeological layers in Guam and the Mariana Islands. It then effectively grew in size and complexity, found in more and more places through time, while people explored and inhabited an ever-widening world of Pacific Oceania. During later periods, the archaeological evidence encompassed the extensive stonework villages and monuments that continue as icons of cultural heritage today.

Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas (CNMI)

The CNMI is composed of 22 islands and islets in the western Pacific. The commonwealth is a part of the Mariana Islands, a chain of volcanic mountain peaks and uplifted coral reefs. The Marianas chain also includes the politically separate United States unincorporated territory of Guam, to the south. Saipan (46.5 sq mi or 120 sq km), Tinian (39 sq mi or 101 sq km), and Rota (33 sq mi or 85 sq km) are the principal islands and, together with Anatahan, Alamagan, and Agrihan, are inhabited. Another island, Pagan, was evacuated in 1981 after a severe volcanic eruption, though people still live there off and on. The capital of CNMI is in Saipan.

The Marianas were settled by people from Island Southeast Asia some 4,000 years ago and were known for their navigation skills and as the builders of latte, capstone pillars that held up houses and community buildings.

Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan was the first European to arrive in the Marianas when he stopped briefly in Guam in 1521. In 1565 Miguel López de Legazpi landed at Umatac/Humåtak, Guam, and proclaimed Spanish sovereignty over the “Islas de las Ladrones” (Islands of Theives) or “Islas las Velas Latinas,” (Islands of the Lateen Sails)–the name given to the islands by Magellan. The permanent colonization of the islands began with the arrival of the Jesuit priest Diego Luis de San Vitores in 1668 who renamed the islands the Mariana Islands in honor of his benefactor, Queen Mariana. Over the next two decades, many islanders were killed in the process of relocation to Guam where they were resettled. Others died from the rapid spread of disease in the settlements, thus further decreasing the population.

Groups of Carolinians, who refer to themselves as the Refaluwasch, from the outer islands of Chuuk and Yap, settled in Saipan in the 1800s after their home islands had been devastated by natural disasters. Chamorros eventually were allowed to move back to Saipan and Tinian in the mid-1800s as well.

After their defeat in the Spanish-American War of 1898, Spain sold the islands to Germany in 1899, and at that time Guam became a possession of the United States. The Germans had little impact on Chamorro and Carolinian culture, though they did introduce new forms of education, bureaucracy, infrastructure and governance. In 1919, after Germany’s defeat in World War I, Japan administered the Mariana Islands (except for Guam) and most of the rest of Micronesia under a mandate from the League of Nations.

Throughout the Japanese period, the Chamorros remained semi-isolated from the Japanese. Intensive agricultural development in copra and then sugarcane was carried out largely by thousands of Japanese nationals and imported labor from other Japanese colonies. Education and other trappings of modernization enhanced some aspects of Chamorro life, and some Chamorros look back on that period as a golden age of economic prosperity and stability. However, other than an acquired taste for imported rice, little that was Japanese remained after the brutal battles on Saipan and Guam in 1944.

In July 1947, the Northern Marianas was recognized as a United Nations Trust Territory administered by the United States, beginning a period of American acculturation and modernization. The traditional Hispanic-Chamorro culture was infused with American economic and political energy. Tourism and the reopened markets on Guam encouraged the people of the Northern Marianas to look beyond their island borders, setting the stage for economic growth.

In 1978, after years of debates and plebiscites, the Northern Marianas entered into a commonwealth association with the United States. Though still under foreign control, the new Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands reintroduced in modern form a measure of autonomy missing from Chamorro culture for over four hundred years.

Currently, tourism is the biggest economic driver of the Northern Marianas.

Federated States of Micronesia (FSM)

Together, the four states of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) are comprised of around 607 islands (a combined land area of approximately 702 sq km or 271 sq mi) that cover a longitudinal distance of almost 2,700 km (1,678 mi) just north of the equator. They lie northeast of New Guinea, south of Guam and the Marianas, west of Nauru and the Marshall Islands, east of Palau and the Philippines, about 2,900 km (1,802 mi) north of eastern Australia and some 4,000 km (2,485 mi) southwest of the main islands of Hawai’i.

While the FSM’s total land area is quite small, it occupies more than 2,600,000 sq km (1,000,000 sq mi) of the Pacific Ocean. The capital is Palikir, located in Pohnpei Island, while the largest town is Weno, located in Chuuk.

Each of its four states is centered on one or more main high islands, and all but Kosrae include numerous outlying atolls. People from Island Southeast Asia first settled in Chuuk, Kosrae, Pohnpei and Yap some 3,000 years ago. Each of the islands has its own language, some with several dialects. The people interacted with each other as well as with the Chamorros of the Marianas throughout their history.

In 1525 Portuguese sailors came upon Yap and Ulithi. Spanish expeditions later made the first European contact with the rest of the Caroline Islands. Spain claimed sovereignty over the Caroline Islands until 1899. At that time, Spain withdrew from its Pacific insular areas and sold its interests to Germany, except for Guam which became a territory of the United States. German administration encouraged the development of trade and production of copra. In 1914, the German administration ended when the Japanese navy took military possession of the Marshall, Caroline and Northern Mariana Islands.

Japan began administering the islands under a League of Nations mandate in 1920. Extensive settlement in the region resulted in a Japanese population of more than 100,000. The indigenous population was then about 40,000. Sugar cane, mining, fishing and tropical agriculture became the major industries. As World War II began, Japan’s focus turned to war and prosperity in the region ended. By the war’s conclusion in 1945 most infrastructure had been destroyed by US bombing.

After the war the newly formed United Nations created the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) in 1947. Ponape (then to include Kusaie), Truk, Yap, Palau, the Marshall Islands and the Northern Mariana Islands, together constituted the TTPI administered by the US.

In July 1978, following a Constitutional Convention, the people of four of the former Districts of the Trust Territory, Truk (now Chuuk), Yap, Ponape (now Pohnpei) and Kusaie (now Kosrae) voted in a referendum to form a Federation under the Constitution of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). Upon implementation of the FSM Constitution on 10 May 1979, the former Districts became States of the Federation, and in due course adopted their own State constitutions. The Compact of Free Association (COFA) with the US was signed in October 1982, and went into effect in November 1986. The Compact was renewed in 2004, and allows for nationals of FSM to live, work and travel freely in the US and its territories, while allowing the US to maintain their military strategic interests in the area. The US also provides postal services.

The FSM’s economic activity consists of subsistence agriculture, fishing and tourism. Financial assistance from the US is the primary source of revenue. Geographical isolation and a poorly developed infrastructure are major impediments to long-term growth. Foreign commercial fishing fleets pay for the right to operate in FSM territorial waters.

Visitors come to the FSM for scuba diving and to see the ancient ruins of Nan Madol on Pohnpei, stone money and manta rays in Yap and to see the sunken World War II fleet in Chuuk.

Guam

Guam, the largest and southernmost of the Mariana Islands chain, has a unique and complex cultural history. Located in the Western Pacific in the geographic region known as Micronesia, Guam is well known for its strategic military and economic position between Asia and the North American continent, but is less known for its remarkable history and resilient people.

Inhabited for thousands of years, the Marianas are home to one of the oldest Pacific Island cultures. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Marianas Islands were one of the first places to be settled by seafaring peoples, possibly from Island Southeast Asia, more than 3,500 years ago. Although it is uncertain whether the islands were settled in waves of migration or all at once, the Mariana Islands appear to have been continuously occupied by people who shared the same culture and language that eventually became known as Chamorro.

Guam not only has a unique ancient history, but a complex colonial history as well. Guam is the site of the first Roman Catholic mission and formal European colony in the Pacific islands. In fact, the last 400 years of Guam’s history are marked by administrations of three different colonial powers: Spain, the United States and Japan.

With each administration, came new challenges and changes for the Chamorro people. As a Spanish colony, the Chamorro people adapted to influences regarding religion, social organization and cultural practices from Spain, Mexico and the Philippines.

The ceding of Guam to the United States as an unincorporated territory after the Spanish-American War in 1898 introduced Chamorros to democratic principles of government and the modern American lifestyle, while keeping them subjects of a sometimes oppressive US naval administration.

Guam also had a unique position in World War II, when Japan invaded the island shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. For the next three years, Guam was one US territory occupied by Japanese forces, and the Chamorros were thrown into a war not of their making, until the Americans returned in 1944 to reclaim the island.

The political maneuverings after World War II and the post war buildup led to even more expansion of US military interests in Guam and the rest of Micronesia, with Guam becoming a hub for economic and commercial development. The easing of military restrictions for entering Guam and the establishment of a local, civilian government, have made the island an ideal place for people from all over the world to visit, go to school, find jobs or pursue a variety of economic interests.

The different eras of Guam’s history are highlighted with moments of resilience, strength, adaptation and innovation as the Chamorro people have found ways to adapt to the challenges of cultural and historical change. Today, Guam has a diverse population that enjoys a rich, multicultural, modern and urban lifestyle, but in its heart endures the spirit, language and culture of the indigenous Chamorro people, for whom Guam has always been “home.”

Kiribati

Kiribati consists of about 32 atolls and one solitary island (Banaba), extending into the eastern and western hemispheres, as well as the northern and southern hemispheres. It is the only country that is situated within all four hemispheres.

The groups of islands are Banaba (Ocean Island): an isolated, raised-coral island between Nauru and the Gilbert Islands; Gilbert Islands: 16 atolls located some 1,500 km (932 mi) north of Fiji; Phoenix Islands: 8 atolls and coral islands located some 1,800 km (1,118 mi) southeast of the Gilberts; Line Islands: 8 atolls and one reef, located about 3,300 km (2,051 mi) east of the Gilberts and Banaba. Total land area is about 313 sq mi (811 sq km)

Banaba was once a rich source of phosphates but was mined out years ago. The rest of the land in Kiribati consists of the sand and reef rock islets of atolls or coral islands, which rise only one or two meters above sea level. Kiritimati (Christmas Island) in the Line Islands is the world’s largest atoll.

Based on a 1995 realignment of the International Date Line, the Line Islands were the first area to enter into a new year in the year 2000. For that reason, Caroline Island has been renamed Millennium Island. The majority of Kiribati, though, including the capital, is not first to enter a new year, even New Zealand has an earlier new year.

Known locally as “Tungaru,” the modern history of Kiribati began with the arrival of Micronesians, which took place between 1,500 to 2,000 years ago. Other islanders from Fiji and Tonga arrived about the 14th century and meager with the older groups forming the traditional i-Kiribati Micronesian society and culture. European contact began in the 16th century with the arrival of whalers, slave traders and merchants. Kiritimati was named “Christmas Island” by Captain James Cook on his third Pacific voyage on Christmas Eve in 1777. In 1820, the western group of islands was named the Gilbert Islands, after a British captain named Thomas Gilbert.

The arrival of the first Protestant missionaries in the late 1850s marked the beginning of Christianity in Kiribati. The second wave of Christian missionaries were Roman Catholic priests of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart who landed on the island of Nononuti in 1888. Since then, Christianity has become an integral part of the Kiribati culture. The first i-Kiribati priest was ordained in 1978 and later became Bishop of the Kiribati diocese.

One of the notable visitors to Kiribati was Robert Louis Stevenson (author of literary titles Treasure Island and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, among others) in 1889. Setting sail for the Pacific islands in 1888 Stevenson spent time on the Kiribati atolls of Abemama and Butaritari (in the Gilbert group). Abemama Atoll is where Tyrant-chief Binoka resided, who was immortalized by Stevenson in his book In the South Seas.

In 1892, Kiribati became a British Protectorate. In 1916 the Ellice Islands were combined with the Gilbert Islands to form the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, along with the Fanning and Washington islands. Kirimiti Atoll was added in 1919, and the Phoenix Islands in 1937.

Tarawa and the some of the other islands in the Gilbert group were occupied by Japanese forces during World War II. Tarawa was the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the war between Japan and the United States. US Marines landed in 1943 trying to dislodge the Japanese defenders.

The Gilbert Islands and Ellice Islands (now Tuvalu) had separated from the group in 1975 and were granted internal self-government by Great Britain. Kiribati adopted internal self-government and a ministerial system in 1977. In July 1979, with a population of less than 60,000, Kiribati achieved independence. After long negotiations and court hearings, Banaba remained part of Kiribati. As part of the treaty formation, the United States relinquished 14 islands in the Phoenix and Line island groups to the new nation of Kiribati. Thus, using the name “Kiribati” acknowledges those islands not considered part of the Gilbert group of islands.

Kiribati is one of the poorest countries in the world due to its small land area, geographic dispersion across 5,000 km of ocean, remoteness from major markets, high vulnerability to natural forces including climate change and sea-level rise, and scarce natural resources. The economy depends on foreign assistance and revenue from fishing licenses to finance its imports and development budget.

Republic of the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands are located near the equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the International Date Line. The country’s population is spread out over 29 coral atolls, and 1,156 individual islands and islets, arranged like two parallel chains running from the northwest to the southeast. The islands share maritime boundaries with the Federated States of Micronesia to the west, Wake Island to the north, Kiribati to the southeast, and Nauru to the south. About 31,000 of the islanders live on Majuro, which is also the capital.

The Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) was first settled by Micronesian navigators about 2,000 years ago. The Marshalls derives its name from British Captain William Marshall, who explored the area with Captain Thomas Gilbert in 1788. The atolls were not a cohesive entity until Europeans named and mapped them. The indigenous people called the islands Rālik-Ratak for the leeward and windward chains of atolls. The major inhabited atolls of the eastern or windward chain include Mili, Majuro, Arno, Aur, Maloelap, Wotje, Likiep, Ailuk and Utirik. The major islands of the western or leeward chain are: Ebon, Namorik, Kili, Jaluit, Ailinglapalap, Namu, Ujae, Lae, Kwajalein, Rongelap, and Bikini. Two isolated atolls, Eniwetok and Ujelang are west of the Ralik chain. The total area covered by the two chains is more than 300,000 sq mi (776,996 sq km).

There are no high islands among the Marshalls. Rainfall in the southern islands can average about 180 inches per year, such as in Majuro. However, there is much less rainfall in the northern islands, making them particularly vulnerable during periods of drought or El Niño.

The islands were subsequently controlled by Spain, Germany, Japan and then by the United States after World War II. When the war ended with Japan’s defeat, the US was given administrative control under the newly formed United Nations, serving as a trustee.

For almost 40 years the islands were under US administration as the easternmost part of the United Nation’s Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI). The US performed nuclear testing on some of the atolls between 1947 and 1962, most notably Bikini and Enewetak. Exposure to nuclear fallout occurred on nearby atolls, leaving long lasting environmental destruction, health problems and social challenges for the Marshallese.

In 1986 the islands gained independence under a Compact of Free Association with the US. Under the terms of that agreement, the US provides significant financial aid that now exceeds $1 billion. The US uses Kwajalein for a military base, and from there, controls a missile testing range.

The modern economy combines a small subsistence sector with a modern urban sector. The subsistence economy consists of fishing and the production of breadfruit, banana, coconut and taro. In the northern islands, pandanus is substituted for breadfruit. Pandanus is also harvested for making handicrafts. There is also a strong service economy on Majuro and Ebeye as people who live on these islands have jobs at the US Army installation on Kwajalein Atoll.

Republic of Nauru

Nauru is a 21 sq km (8 sq mi) oval-shaped island in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, located 42 km (26 mi) south of the Equator, between the Solomon Islands and Kiribati. The island is surrounded by a coral reef, which is exposed at low tide and dotted with pinnacles. The presence of the reef has prevented the establishment of a seaport, although channels in the reef allow small boats access to the island. A fertile coastal strip 150 to 300 m (490 to 980 ft) wide lies inland from the beach. Coral cliffs surround Nauru’s central plateau. The highest point of the plateau, called the Command Ridge, is 71 m (233 ft) above sea level.

The only fertile areas on Nauru are on the narrow coastal belt, where coconut palms flourish. The land surrounding Buada Lagoon supports bananas, pineapples, vegetables, pandanus trees and indigenous hardwoods such as the tomano tree. There are some seabirds, but no indigenous land mammals.

Nauru was one of three great phosphate rock islands in the Pacific Ocean. The others were Banaba (Ocean Island) in Kiribati and Makatea in French Polynesia. The phosphate reserves on Nauru are almost entirely depleted. Phosphate mining in the central plateau has left a barren terrain of jagged limestone pinnacles up to 15 m (49 ft) high. Mining has stripped and devastated about 80% of Nauru’s land area, and has also affected the surrounding Exclusive Economic Zone; 40% of marine life is estimated to have been killed by silt and phosphate runoff.

There are limited natural fresh water resources on Nauru. Rooftop storage tanks collect rainwater. Average rainfall is about 200 cm (79 in), but recurrent droughts can cause problems. Temperatures are warm and tropical. The islanders are mostly dependent on three desalination plants housed at Nauru’s Utilities Agency. Nauru is also susceptible to the hazards of global warming and rising sea levels.

The Nauruans, who settled the island about 2,000 years ago, are a distinct people with their own language and culture. The Nauruan people called their island “Naoero.” The name “Nauru” was the way English language speakers heard it. The first westerner to visit Nauru was a whaling Captain John Fearn who arrived in 1798, giving it the name Pleasant Island. The people had little contact with Europeans until whaling ships, traders and beachcombers began to visit regularly in the 1830s. Europeans called Nauru “Pleasant Island.”

The introduction of firearms and alcohol destroyed the social balance of the 12 clans living on the island and led to a ten-year internal war, which reduced the population to around 900 by 1888; in 1843 there had been 1,400 people on Nauru. Peace was only restored when Germany took action to remove firearms from the island. The island was allocated to Germany under the 1886 Anglo-German Convention.

Phosphate was discovered a decade later and the Pacific Phosphate Company started to exploit the reserves in 1906, by agreement with Germany. The island was captured by Australian forces in 1914 and administered by Great Britain. In 1920 the League of Nations gave Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand a Trustee Mandate over the territory, though the island was administered by Australia. The three governments bought out the Pacific Phosphate Company and established the British Phosphate Commissioners, who took over the rights to phosphate mining.

During the Japanese occupation (1942–45) of World War II, 1,200 Nauruans were deported to work as laborers to Chuuk, Micronesia, where 463 died as a result of starvation or bombing. The survivors were returned to Nauru in January 1946. Nauru’s population had fallen from 1,848 in 1940 to 1,369 in 1946. After the war, the island became a UN Trust Territory, administered by Australia in a similar partnership to the previous League of Nations mandate, and it remained a trust territory until independence in 1968. The Naurauns had had a Council of Chiefs since 1927 to represent them in an advisory capacity to the Australian government, but the Nauruans pressed the UN and the government for further political power.

Anticipating the exhaustion of the phosphate reserves, a plan by the partner governments to resettle the Nauruans on Curtis Island, off the north coast of Queensland, Australia, was put forward in 1964. However, the islanders decided against resettlement. Legislative and executive councils were established in 1966, giving the islanders a considerable measure of self-government, including control of the phosphate industry, which occurred in 1970.

Nauru’s economy is based on phosphate mining, offshore banking, and coconut products to a lesser degree. Primary phosphate reserves were exhausted, and mining ceased, but in 2006–07, mining of a deeper layer of “secondary phosphate” began, though it is not as prosperous as the original layer. The other major source of government revenue is the sale of fishing rights in Nauru’s territorial waters. Nauruans also receive financial support from Australia, Taiwan and New Zealand, partially to rehabilitate the environmental damage caused by phosphate mining. Nauru officially joined the United Nations in 1999.

Republic of Palau

Palau is an archipelago located in the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost portion of the Caroline Islands in Micronesia. Its most populous islands are Angaur, Babeldaob, Koror and Peleliu. The latter three lie together within the same barrier reef, while Angaur is an oceanic island several miles to the south. About two-thirds of the population live on Koror.

The coral atoll of Kayangel is north of these islands, while the uninhabited Rock Islands (about 200 islands) are west of the main island group. A remote group of six islands, known as the Southwest Islands, some 375 mi (604 km) from the main islands, make up the states of Hatohobei and Sonsorol.

Palau is comprised of several cultures and languages. Ethnic Palauans predominate, inhabiting the main islands of the archipelago. Descendants of the Carolinian atolls, especially Ulithi, settled on Palau’s southern atolls of Hatohobei, Sonsorol, Fannah, Pulo Anna, and Merir.

The islands have a total land area of 191 sq mi (495 sq km). Palau is best known for its 70-mile-long (113-km-long) barrier reef which encloses spectacular coral reefs and a lagoon of approximately 560 sq mi (1,450 sq km)–a diver’s paradise.

Palau was first settled some 3,000 years ago. Not much is known of the early history of the islands, but it is clear the Palauans participated in the wide-ranging Micronesian trade system, with some interaction with Malay traders. In the 19th century Palau was loosely part of the Spanish Pacific. After the Spanish-American War in 1898, Palau was among the islands sold to Germany by Spain. In 1914 the islands were occupied by the Japanese, a control later confirmed as a League of Nations Class C Mandate. From 1909 until 1954, phosphate mining took place on Angaur, originally by the Germans, then the Japanese, and finally by Americans. Angaur, as well as Peleliu, are major World War II battle sites between Japanese and American forces. The US took possession of the islands from Japan in 1944, during the war after fierce fighting.

Starting in 1947, Palau was part of the United Nations Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, under the administration of the US government. Palauans established their own constitutional government in 1981. While Palau wanted to have a free association political arrangement with the US, ratification of a Compact of Free Association was delayed by constitutional nuclear-free clauses, which required a 75% vote of the people. Palauans also feared US military land use.

Between 1983 and 1991 Palau conducted seven plebiscites and experienced escalating violence, including the assassination of the first elected president. After a three-year cooling-off period and clarifying statements by the US on the conditions under which the US military might be present on the islands, the compact was approved, the trusteeship terminated, and the nation formally recognized by the United Nations in 1994, marking Palau’s independence. Palau is known for its progressive environmental stance.

Tourism from Asia and from from divers worldwide drive Palau’s economy. It is one of the wealthier Pacific Island states. Besides tourism, subsistence agriculture and fishing, along with financial assistance from the US, contribute to the economy.

For further reading

Campbell, IC. A History of the Pacific Islands. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989.

Hanlon, David L. Remaking Micronesia: Discourses over Development in a Pacific Territory, 1944-1982. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1998.

Hezel, Francis X. The New Shape of Old Island Cultures: A Half Century of Social Change in Micronesia. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001.

Howe, KR, Robert C. Kiste, and Brij V. Lal, eds. Tides of History: The Pacific Islands in the Twentieth Century. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1994.

Pacific Asia Travel Association. “Micronesia Tour.” Micronesia Chapter.

Petersen, Glenn. Traditional Micronesian Societies: Adaptation, Integration, and Political Organization. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009.