Manila Galleon Crew Members

Table of Contents

Share This

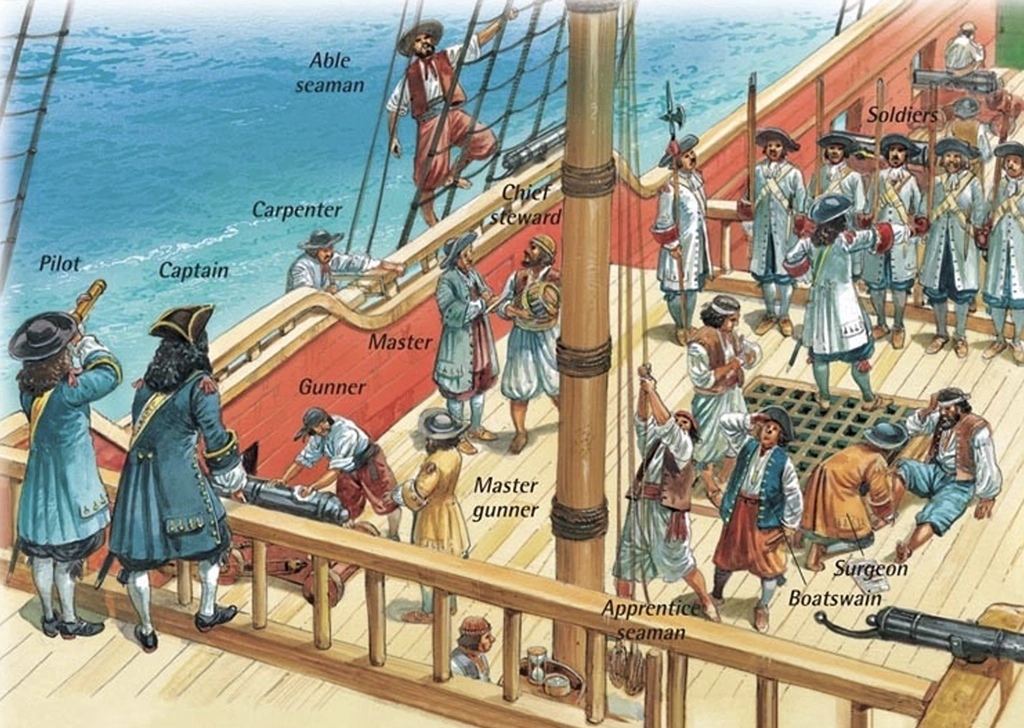

Personnel of the Manila Galleons

The galleons that passed through the Marianas carried scores of crew members in addition to soldiers and colonial or mission helpers on their way to the Marianas and the Philippines. These individuals conceivably could have engaged with the CHamoru people in interactions of trade and cultural exchange under various circumstances. Some of the crew members were shipwrecked in the islands, and some chose to stay and married CHamoru women.

In addition to Spaniards, many crew members were native Filipino or Mexicans who brought with them their language, customs and other traditions and beliefs that both impressed, and in many cases, were adopted by the CHamoru people. What kinds of people made up these galleon crews?

Crew size

Crew size depended on the size of the galleon. Smaller galleons functioned with a crew of 50, while the crew of the larger galleons could number more than 400.

For example, two galleons, the Santisima Trinidad (in 1754 and 1755) and the Nuestra Señora del Rosario (1749) had crews of over 384, as presented in the table which you can access by clicking the link below.

Crew positions

The youngest of the crew were the pages or ship’s boys. Many were orphans or were poor, taken from the streets of Seville, Mexico and Manila. Most were entered into service at the age of eight, although boys as young as seven were known to be pressed into service. Those with family ties to a high-ranking officer or who were able to forge a friendship with a crew member had the best protection. In this case, the page was exclusively at the service of his protector, unlike “ship’s pages” that were at the service of the entire crew.

Ship’s pages were the least skilled of the crew and, as a result, had to carry out menial duties such as scrubbing and cleaning the ship, preparing the distribution of provisions, calling the crew to meals and cleaning up afterwards. They were also charged with night watches, and when the night was over, to chant “Buenos Dias” in the morning. The ships pages also kept track of time by turning the sand clock every half hour and reciting psalms or litanies that were answered in chorus by the crew. Every afternoon the pages recited the tenets and principal prayers of the Christian faith. In addition to these duties, the pages took orders from all of the sailors and apprentices on the ship.

Apprentices were sailors in training. Officially, they were to take orders from sailors and officers pertaining to the ship’s handling, but many times their superiors used them for personal services such as cooking, cleaning and grooming. Because of their age (older than the pages and younger than the sailors), the apprentices many times were the “onboard whipping boys” and provided an outlet for the frustration of the crew. At the age of 20, successful apprentices received a document certifying him as a sailor.

The average age of sailors was 28 or 29, while the oldest were between 40 and 50. Sailors handled the helm (a difficult task before the wheel was invented). They set the course for the ship by watching the trim of the sails and the compass while implementing the orders of the pilot. They handled the rigging and ropes during maneuvers and attended to the sounding line that determined the water’s depth. A good sailor was one that could thread a cable through an anchor ring or deploy a sail in storm conditions. Intelligent and skilled sailors could advance to the position of gunner or sea officer and in some cases, if they had the means and wherewithal to stop work and attend classes in Seville, they could eventually advance to the position of pilot.

Gunners were expert sailors that had mastered the use of the cannon. They had to know how to make gunpowder, fill grenades, select the type of projectiles to use against an enemy ship, maneuver, load and fire the cannon, maintain it and keep it steady aboard the moving ship. The officer in charge of the artillery was a sergeant. A large proportion of sergeants and gunners were not Spanish but Germans, Flemings and Italians. In later years, due to serious efforts to increase the proportion of Spaniards in these positions, Andalusian and Basque gunners increased significantly.

The carpenter, caulker and diver made up the repair team of the ship. The carpenter was indispensable on a ship built mainly of wood. Typically the carpenter was the oldest crewmember on the ship. A good carpenter had to know how to cap a breach in the hull, make a pulley, a cabin or a launch. The carpenter and caulker were responsible for the maintenance of the hull. The caulker was tasked with filling the juncture of the hull planking and deck with oakum and tar. He was also charged with the maintenance of the bilge pumps. When the efforts of the carpenter and the caulker were not sufficient to repair a leak or free a blocked rudder, the diver would have to attempt to repair it either at sea or in port depending on the severity of the problem.

The scribe registered the cargo, wrote wills, and recorded judicial proceedings.

The cooper repaired containers, especially the barrels that carried water, wine and other provisions.

The surgeon was charged with the physical health of the crew while the chaplain was concerned with their spiritual heath.

The steward was in charge of the food stores and for dispensing rations to the crew. His duties also included overseeing the re-provisioning and moving of the provisions around the ship as needed. Punishing those involved in stealing food was another duty.

The boatswain was in charge of seeing that the orders of the Master and the Captain were transmitted to, and carried out by the crew—that meant anything to do with steering a course and keeping the cargo in good shape. The boatswain was responsible for ensuring the cargo was stowed well and maintained throughout the voyage, maintaining all mechanisms of the ship and ordering repairs. He was also in charge of directing the crew during maneuvers on board the ship. He accomplished this with a whistle from the poop deck, while his assistant, the boatswain mate, directed the work at prow.

The boatswain mate was primarily charged with being in command of the ships auxiliary craft. These crafts were used to load and unload the ship, to tow the ship when needed and to go in front of the ship to take soundings to avoid shallow water. The boatswain mate was also in charge of disciplining apprentices and pages.

The highest-ranking positions on the ship were the pilot, the master and the captain.

The pilot was responsible for the navigation of the ship, ensuring that the vessel safely reached its destination. A pilot had to recognize the sea and landscapes where he sailed, be able to read the clues from the ocean, waves and sky, the winds and the animals. He needed to be able to predict a storm and have the theoretical knowledge to chart a course, and calculate his position using mathematical formulas and computations. While the pilot required knowledge in the sciences, experience and traditional knowledge was just as valuable. Because of the experience required for this position, the average age of pilots was over 40 years.

The master was in charge of the financial and administrative aspects of the voyage. His job was to see to it that the ship had all the necessary resources, licensing and permits to carry out its mission. He was responsible for not only obtaining the cargo, but the crew, ship’s equipment, arms and provisions. He needed to ensure that all the material and human resources required to reach its destination were obtained and that the passengers and cargo were delivered in good condition. He was the administrator of the ship and had to certify to the owners of the ship, owners of the cargo and the government officials that all contracts and laws were followed and taxes paid.

According to Pablo E. Perez-Mallaina in Spain’s Men of the Sea, the captain’s sole duty was to defend the ship from enemy attack. The captain was the supreme commander in this case. But in the majority of cases, he writes, “this charge was more or less honorific, and the onboard activity of the captain consisted in nothing more that directing the defense of the ship in case of enemy attack.” He says that the general of the fleet could honor a distinguished gentleman by naming him as captain. The so-called “captain” would travel as a passenger with no specific duties.

On the westward voyage, a Maestre de Plata or Master of the Silver was in sole custody of the chests of silver containing two or three million pesos destined for the shippers in Manila.

Other positions affiliated with the galleons were:

Constables were tasked with maintaining order on the ships. Water constables were charged with the rationing of water.

Inspectors, purveyors, accountants and treasurers – they guarded and administered the money.

The General was the supreme commander of the fleet.

The Admiral was the second-in-command of the fleet.

The general and admiral of each fleet was first selected for each expedition by the House of Trade and confirmed by the Spanish monarch and the Council of the Indies. Their employment was for the duration of the expedition. Upon their return and the completion of their expedition they were unemployed. This unstable employment led many to seek outside sources of income. Many generals and admirals owned ships that they leased to the king.

Makeup of the crew

Mortality rates were high, especially in the early years of the Manila galleon trade. It was not uncommon for a ship to arrive in Manila from Acapulco with only a fraction of their crew still alive. The majority would have died from starvation, disease and scurvy. Spanish officials in Manila found it increasingly difficult to find men to crew their ships, especially for the long and arduous return voyage to Acapulco. As a result, many indios of Filipino and Southeast Asian origin made up the majority of the crew. Less than a third of the crew was Spanish and they usually held key positions onboard the galleon.

By the late 1700’s indios from the Philippine islands were valued for their seamanship. Francisco Leandro de Viana wrote in 1765 about the native seaman serving on the Manila galleons:

There is not an Indian in these islands who has not a remarkable inclination for the sea; nor is there at present in all the world a people more agile in maneuvers on shipboard, or who learn so quickly nautical terms and whatever a good mariner ought to know. Their disposition is most humble in the presence of a Spaniard, and they show him great respect; but they can teach many of the Spanish mariners who sail these seas.

de Viana goes on to remark,

The little I understand about them makes me think that these are people most suited for the sea; and if the ships are manned with crews one third Spaniards and the other two-thirds Indians, the best mariners of these islands can be obtained, and many of them can be employed in our warships. There is hardly an Indian who has sailed the seas who does not understand the mariner’s compass, and therefore on this [Acapulco] trade-route there are some very skilful and dexterous helmsmen.

It should be noted that Guam at the time was considered to part of the Philippine Islands and it is likely that someone from Guam served onboard one of the ships used in the Manila Galleon trade.

Another source of crewmembers were deportees, prisoners and other undesirables from Spain and the colonies. Many times individuals were sentenced to serve as crew on royal ships. One such case was Fernando Antonio Izquierdo, who in 1754 was found guilty of murdering Cayetano Méxica, a Mexican surgeon serving in Anigua, Guam. Izquierdo was sentenced to serve on the Royal Manila Galleons for a period of ten years. He would receive rations but no pay.

Because the deportees, prisoners and undesirables could come from South and Central America, Europe and Asia, the makeup of the crew was very diverse. Also, because finding skilled Spanish seamen became a problem, some of the ships officers were foreigners. One such case was the Frenchman, Antoine Limarie Boucourt who was the pilot on the Santissima Trinidad in 1755.

For further reading

Blair, Emma H., James A. Robertson, and Edward G. Bourne, eds. The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803. Vols. 1-55. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1903-1909.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Spanish Governor of the Mariana Islands and the Saga of the Palacio. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 2005.

Lévesque, Rodrique. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vol. 20, Bibliography of Micronesia, Ships through Micronesia, Cumulative Index. Quebec: Lévesque Publications, 2002.

Mateo, José EB. “The arrival of the Spanish galleons in Manila from the Pacific Ocean and their departure along the Kuroshio stream (16th and 17th centuries).” Journal of Geographical Research, no. 47 (2007): 17-38.

Pérez-Mallaìna, Pablo E. Spain’s Men of the Sea: Daily Life on the Indies Fleet in the Sixteenth Century. Translated by Carla Rahn Phillips. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Peterson, Andrew. “What Really Made the World go Around?: Indio Contributions to the Acapulco-Manila Galleon Trade.” Explorations a Graduate Student Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 11, no. 1 (2011): 3-18.

Schurz, William Lytle. The Manila Galleon. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, Inc., 1959.

Searles, PJ, USN Commander. “Spanish Galleons.” Guam Recorder, 1940.