Ma Uritao

Table of Contents

Share This

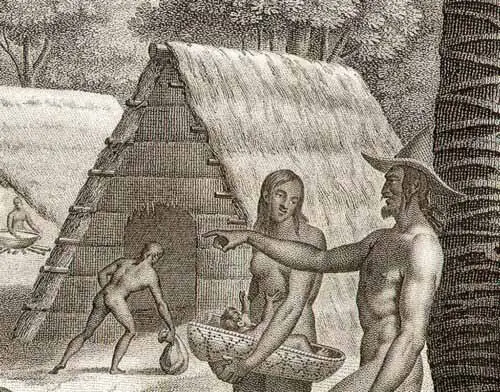

Young women who trained young men

Ma uritao, an ancient CHamoru/Chamorro term used before Christianity was introduced to the Chamorro/CHamoru people, describes young unmarried women who resided at the guma’ uritao (bachelors’ house) to sexually train young men as a part of their education to become men.

Prior to the 16th century European arrival, CHamoru society was organized into clan settlements. Clans were formed based on familial bonds and obligations on the woman’s family and were a significant source of moral, material, and financial support.

Clans had a few main gathering places, one of which was guma’ uritao or the male bachelor house. At puberty, unmarried CHamoru males would leave their mother’s home and live at the guma’ uritao. In this setting, uritaos (bachelors) learned the life-skills and knowledge of their male elders, such as canoe-making, house-building, sailing, fishing, hunting, farming, and fighting. All of these skills were necessary to sustain the health of the clan.

Ma uritao were unmarried young women in a clan, who were chosen to serve an integral role in the cultivation of uritaos for another clan’s guma’ uritao. Since ancient CHamoru society valued children, ma uritaos who got pregnant were equally valued for marriage purposes rather than women who didn’t serve as ma uritao. This social practice also increased ma uritao’s parents’ social status and resources as well as her chances of a having good marriage.

Demise of Guma Uritao

From the 17th century, Catholic evangelization lead by Spanish Jesuit missionaries and accompanied by military soldiers for protection, was the beginning of the end of many ancient CHamoru institutions. It was in this century that effective expansion and impact of the Catholic worldview on CHamoru society were assured by the Spanish military.

What was once an ancient social institution–necessary to maintain CHamoru social life and survival–guma’ uritao were subjected to Christian moral scrutiny including ma uritao. Deemed a moral aberration that encouraged sexual promiscuity, the demise of guma’ uritao and the ma uritao from the CHamoru social landscape were replaced by the Spanish missions which would become the social centers of a Christianized people.

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

García, Francisco. The Life and Martyrdom of Diego Luis de San Vitores, S.J. Translated by Margaret M. Higgins, Felicia Plaza, and Juan M.H. Ledesma. Edited by James A. McDonough. MARC Monograph Series 3. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 2004.

Hattori, Anne Perez. Colonial Dis-ease: U.S. Navy Health Policies and the Chamorros of Guam, 1898-1941. Pacific Islands Monograph Series 19. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2004.

Herman, RDK. “Guam: Inarajan – Native Place: Village.” Pacific Worlds, 2003.

Jorgensen, Marilyn A. Guam’s Patroness: Santa Marian Kamalen. N.p., 1994.

Lévesque, Rodrigue. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vol. 20, Bibliography of Micronesia, Ships through Micronesia, Cumulative Index. Québec: Lévesque Publications, 2002.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.