Guam’s Strategic Value

Interpretive essay: Location, harbor proves worth

The strategic significance of Guam is due to the enduring importance of its location and its topography to major maritime nations in the Pacific Ocean. Guam, some 30 miles long and 10 miles wide, is the largest of the Mariana Islands, an archipelago of high volcanic islands in Micronesia, a huge expanse of small islands scattered across the western Pacific.

On the axis that crosses 5,000 miles of the Pacific between Hawai’i and Asia, Guam is the only island with both a protected harbor and sufficient land for major airports. Guam is also the largest landfall for communications, shipping, and military installations on the nearly 3,000-mile north-axis from Japan to Papua New Guinea and Australia. This geography means that whoever controls Guam has access by air and sea to China to the west, to Hawai’i and North America to the east, to Southeast Asia from the north and to Japan from the south. These geopolitical factors make Guam a valuable strategic nexus similar to other small island bastions in military history and maritime trade such as Hawai’i, Gibralter, Malta and Singapore.

Good stop for provisions

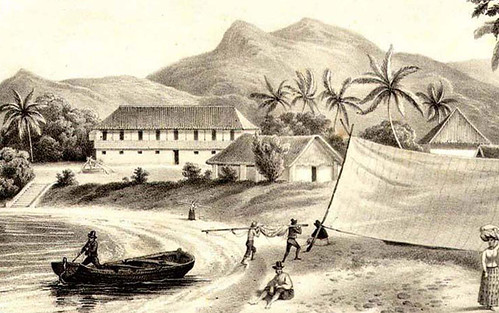

The importance of Guam was recognized by Spain after Ferdinand Magellan made the first European landfall there in 1521 on the way to the Philippines and the first circumnavigation of the world. In the following decades Guam became a necessary stop for provisions for Spanish Galleons on their voyages from Mexico to Manila in pursuit of trade with China.

These stopovers led Jesuit missionaries in 1668 to initiate conversion of the native Chamorro people of the Marianas to Catholicism at first by choice and, after a rebellion, by force of arms (and to name the islands for Spain’s Queen Mariana). To protect the missionaries and its line of communications across the Pacific from other European powers, Madrid stationed solders on Guam under a military governor.

After defeating Spain in the Spanish-American War of 1898, the United States kept Guam as a part of a trans-Pacific line of communications (including the islands of Hawai’i, Midway and Wake) in a manner similar to the Spaniards to support the newly acquired Philippines. Guam was then needed as a coaling station for steam-powered ships. After the Americans neglected to acquire Spain’s other islands in Micronesia, another expanding military power – Imperial Germany – purchased the northern Mariana Islands and the rest of Micronesia from Spain in 1899.

Close to Asia

World War I brought a modernizing and powerful Japan into Micronesia to replace a defeated Germany. The Japanese soon viewed Guam and the Philippines as obstacles in their southward march to gain access to the raw materials of Southwest Asia for Japan’s growing industries. Both Japan and America began to plan for war against each other (called War Plan Orange by the US Navy) with Guam an obvious target for Japan. In response, the Americans initiated human and radio intelligence gathering in Micronesia and Asia from Guam.

Strategic rivalries in the Pacific were temporarily calmed in 1922 by the Washington Naval Conference at which treaties were signed limiting the number of warships the five major naval powers could construct. Washington officials, to the dismay of the US Navy, agreed to halt any fortification of Guam for ten years. A geopolitical calm then settled over the western Pacific. However, the agreement was not renewed in 1932. And in 1941 the poorly fortified island of Guam was quickly taken over by the Japanese.

Having lost Guam, the Americans had to fight their way westward from Hawai’i and northward from Australia, in bloody battles across Micronesia. After the Americans re-occupied the Marianas in 1944, the islands became launch pads for their air assault on Japan that culminated in the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Tokyo’s surrender. Thereafter the Pacific Ocean became – and remains – American, with Guam a Gibralter in the center of Micronesia.

During the cold war that followed, military bases on Guam were a deterrence against the Soviet Union in the American strategy of forward deployment around the edges of Asia. America used Guam to harbor nuclear missile submarines, long-range bombers, satellite and underwater cable communications centers, large facilities for electronic intelligence gathering, and stockpiles of conventional and nuclear weapons. Updated versions of these weapons systems and facilities remain in place on Guam.

Simultaneously, the federal government used Guam to serve American interests as a support base for the Korean War in 1949-53, a base for B-52 bombers in the Vietnam war of 1965-73 (and a haven for South Vietnamese refugees in 1975), as well as a logistical link to the U.S. base on Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean for the 1991 Gulf War and the Iraq War that began in 2003.

Throughout all those wars, the people of Guam remained loyal to the United States despite the fact that Guam is an American colony without full self-government. Now, as of 2022, Guam is being prepared for redeployment of a Marine Corps brigade from Okinawa, additional Air Force units, and regular visits from Navy aircraft carriers as America continues its strong presence in the Asian region.

For further reading

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.

Valle, Maria Teresa del. The Importance of the Mariana Islands to Spain at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century. Edited by Marjorie G. Driver. MARC Educational Series no. 11. Mangilao: Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1991.

Webb, James H., Jr. Micronesia and U.S. Pacific Strategy: A Blueprint for the 1980s. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974.

Willens, Howard P., and Dirk A. Ballendorf. The Secret Guam Study: How President Ford’s 1975 Approval of Commonwealth Was Blocked by Federal Officials. Mangilao and Saipan: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam and Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2004.