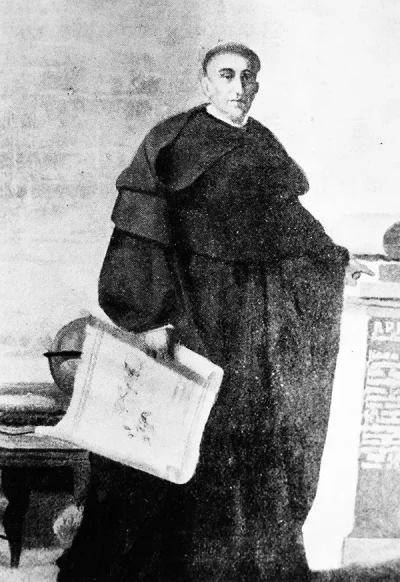

Andres de Urdaneta

Table of Contents

Share This

Discovered return sea route in 1565

Andrés de Urdaneta (1498 – 1568), a Spanish Augustinian friar born in Villafranca de Ordizia in the Basque province of Gipuzkoa, Spain, was a seaman, sailor, navigator and author who became the most knowledgeable European navigator of the Pacific, best known for his discovery of the Tornaviaje, or return sea route from the Philippines to the Americas. He visited the Mariana Islands twice during his lifetime, proposed a permanent Spanish settlement on Guam in 1565, and his accounts provided some of the earliest ethnographic information about the CHamoru/Chamorrro people.

In the first half of the 16th century, Spanish galleons and ships could navigate from America to the Philippines, generally following the trans-Pacific course set by Ferdinand Magellan, but the return voyage proved difficult because ships would face the prevailing easterly winds. Every expedition sent from New Spain (Mexico) during this period was either lost or forced to detour to the Moluccas (an archipelago in eastern Indonesia), where they were taken as prisoners by the Portuguese. Urdaneta would later discover that by climbing to the higher latitudes of the Western Pacific – 30 to 40 degrees north – ships could avoid the easterly winds and catch prevailing westerlies, shortening the trip.

From sailor to missionary

Urdaneta enrolled as a young sailor on the expedition of Jofre de Loaysa and Juan Sebastian Elcano in 1525, which sailed from Spain on the first attempt to exploit the route pioneered by Magellan. The expedition was unable to discover a return route to Mexico and eventually reached the Portuguese-controlled Moluccas where the officers and crewmen were taken prisoners. Urdaneta spent his time in the Moluccas observing the stars, the currents, and the winds, evaluating trading opportunities, Portuguese strength and potential Spanish alliances with local rulers and writing his conclusions in diaries, memoirs and on maps.

On the expedition’s westward crossing of the Pacific during 1526, the surviving vessel, Santa Maria de la Vitoria had stopped at Guam, anchoring off the southwest coast for six days. The expedition traded extensively with CHamorus from coastal villages for vitally needed fresh food and water in exchange for Spanish iron goods. Urdaneta learned a little about the archipelago’s geography, resources and customs from the beachcomber Gozalvo Alvarez de Vigo, a cabin boy on Magellan’s expedition who had deserted and spent four years in the Marianas. This visit would influence Urdaneta’s later proposals for solving the circumnavigation problems of the Pacific.

Repatriated from the Moluccas, Urdaneta arrived at Lisbon, Portugal on 26 June 1536. He planned to continue on to the Spanish Court to present the King with his findings, but at the last moment the Major Guard of the Port of Lisbon, aware of the methods that explorers used to protect their maps, examined all of Urdaneta’s personal belongings and packages. His valuable navigational charts and travel diaries, which could have been used by future Spanish expeditions, were discovered and confiscated, although many were disguised as private letters.

Urdaneta eventually escaped from the Portuguese, and crossed into Spain where he arrived at Valladolid. Using his excellent memory, Urdaneta was able to recall and set down in writing his observations and conclusions from his Pacific exploration and Moluccan sojourn.

Moving to New Spain in 1536, Urdaneta maintained his interest in Pacific exploration by studying the navigational accounts of Spanish voyages that had failed to secure a viable trading base in the Spice Islands (also in Indonesia) or find the return route. He was later invited to command a new Spanish expedition to the Islands of the East, but refused because he believed that the Philippines and the Moluccas were in Portuguese territory, according to treaties Spain had entered with the Papacy and Portugal. The expedition was eventually commanded by Ruy Lopez de Villalobos.

By the mid-16th century, Urdaneta, who had become an Augustinian friar in 1553, was advising the Crown of a strategy he was convinced could solve the problems of circumnavigating the Pacific. He proposed three possible westward routes – north, central and southern – using seasonal wind patterns, with the chosen course depending on the time the expedition sailed from the Pacific coast of New Spain. He also described a strategy for using the seasonal winds of the Western Pacific for the return route.

Guam was a key to Urdaneta’s plan of operations for the proposed central crossing from New Spain, via a series of navigational and provisioning way-stations across the Pacific. Because determining longitude was then largely educated guesswork relying on dead-reckoning, these stations would allow ships to stay on course and better chart their progress across the vast ocean, with its many submerged reefs and dangerous shoals. San Bartolomé (Taongi in the Marshalls) or Wake Island would be the way-station in the central Pacific, while Guam, which Urdaneta had already visited, would serve that important function for the western Pacific.

When the Spanish King Philip II directed the Viceroy of Mexico to prepare another expedition to establish direct Asian-American trade, Urdaneta was asked to help organize the initiative and guide the voyage as senior pilot-navigator. The fleet was to be commanded by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi (who officially claimed the Mariana Islands for the Spanish Crown). Urdaneta accepted under condition that they would not cross the Portuguese line, meaning that the expedition would not attempt to colonize the Philippines or the Moluccas.

Urdaneta thought the Legazpi expedition was to be a reconnaissance, an exploration and intelligence gathering voyage to help rescue survivors of past expeditions, and to begin the evangelization of New Guinea. He believed the expedition would inform the King’s future moves regarding the Philippines and not seek to immediately establish a colony there.

Urdaneta's Guam proposal

Urdaneta was needed for the expedition because his experience and knowledge were indispensable for finding the Tornaviaje and the Spanish Crown apparently accepted his conditions just to convince him to embark. The Spanish Crown intended to colonize the Philippines, even though the islands’ location was still in dispute. Partly because of Urdaneta’s opposition to such a colony, Legaspi was given sealed orders and instructed not to open them until his expedition was 300 miles at sea.

The Legazpi expedition arrived at Guam on 21 January 1565. The pilots thought that they had reached the Philippines, but Urdaneta, who had advised Legaspi of needed course corrections that brought the fleet to Guam, realized where they were when he recognized the distinctive lateen sails of the CHamoru outrigger canoes and heard an old CHamoru asking for “Gonzalo”, the cabin boy and beachcomber, Gonzalo Alvarez de Vigo, who had been repatriated by the Spanish vessel that visited Guam in 1526 with Urdaneta aboard.

At a meeting of expedition leaders during the Legazpi visit, Urdaneta surprised officials by proposing that the fleet not proceed further west, but rather make a permanent settlement on Guam and immediately dispatch one of the galleons for the arduous task of discovering the return route to New Spain – a major goal of the expedition and key to direct Asian-American commerce. He argued that Guam, an unmistakable high island, had been visited by three Spanish expeditions and its location was well charted. The island had ample land, perennial streams, good leeward anchorages, abundant food staples and was strategically located to reach Japan, the China coast, the Philippines and the Moluccas.

Guam would make a useful forward base for further Spanish explorations in search of East Asian commercial opportunities and was advantageously situated for dispatching the ungainly galleons, which could safely maneuver in the Philippine Sea’s seasonal southwesterly winds that Urdaneta believed would allow them to reach northern latitudes where prevailing westerly winds would carry the vessels across the North Pacific to the coast of New Spain.

Most importantly for Urdaneta, a Guam settlement would assure that the initial Crown colony in the region would be in Spanish territory acknowledged under agreements with the Papacy and Portugal. Urdaneta’s proposal for Guam reflected his familiarity with the island and his vision of its role in enabling Spain to expand westward over its designated sphere of influence.

As an opportunity to avoid trespassing into Portuguese territory, Urdaneta’s proposal for a settlement on Guam found favor with his fellow Augustinians as well as virtually all of the expedition leaders attending the meeting. However, Legazpi was unconvinced, responding firmly that his orders directed him unequivocally to the Filipinas to establish a settlement if possible and to launch the search for a return route from there.

For Legazpi, the goal of the expedition was not to settle legal disputes but to find a realpolitik (politically practical) way to establish direct contact between Philippines and New Spain, making the Kingdom of Castile competitive with Portugal in developing potentially lucrative trade with the China coast, Japan and the Spice Islands. Before sailing for Cebu, Philippines on 3 February 1665, Legazpi took possession of Guam and the other islands in the Marianas archipelago in the name of Philip II.

Five months later, on 1 June 1565, Legazpi sent his best-sailing galleon, the San Pedro, from Cebu in the Philippines to New Spain with Urdaneta aboard, who navigated to the north, was able to ride the Kuroshio Current to 42 degrees north, then sailed east and arrived at Acapulco, Mexico on 8 October 1565. This successful voyage and charting of “Urdaneta’s Route” finally made possible the establishment of the trans-Pacific galleon trade and the Spanish colonization of the Philippines.

From Mexico, Urdaneta went to Spain to make a report on the expedition and then returned to New Spain, where he died in Mexico City in 1568.

By Carlos Madrid and Frank Quimby

For further reading

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. The First Taint of Civilization: A History of the Caroline and Marshall Islands in Pre-Colonial Days, 1521-1885. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1983.

Kurlansky, Mark. The Basque History of the World. New York: Walker & Company, 1999.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.