200 years of disruption

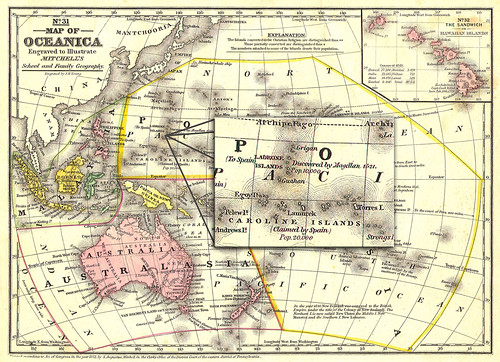

The Age of European Exploration in the Pacific began in 1521 with Ferdinand Magellan’s search for the Spice Islands (now the Moluccas). He was soon followed by many others, and by 1565 Spain had virtually full control of navigation routes across the Pacific. Oceania became, as Pacific historian Oskar Spate called it, a “Spanish lake.”

One of the most significant consequences of the European explorations in the Pacific, starting in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was the Christianization and conquest of the Marianas. This affected traditional navigation by causing the disappearance of a unique form of watercraft, the Chamorro proas, the use of which the inhabitants of Marianas, as observed by early visitors, had clearly mastered. But in the mental framework of the colonizers, the proas were a hindrance for conversion and control of the indigenous people. The Chamorros were forced to abandon their “pagan” ways of life and the proas and other seagoing canoes were actively eliminated.

Trade interruption

The interruption of indigenous interaction between the central Carolines and the Marianas, from the late seventeenth century to the late eighteenth century, was also an indirect consequence of European explorations in the area. There was probably regular contact between the Marianas and the islands of the central Carolines before the arrival of the Europeans in Micronesia.

In 1788, there was an attempt to re-establish such routes, by the seaman “Luito of Lamotrek” from the Carolines who reached Guam with two canoes in that year. It was said that the knowledge and details of the sea route to “Waghal,” as Guam was known in the southern islands, had been passed down through traditional chants from one generation to another. The information was preserved in the memory of the community and was instrumental in the restoration of that traditional sea route.

The Carolinians told the Chamorros they had stopped coming to Guam and the other Mariana islands because they assumed that others who had traveled to the Marianas and not returned were killed.

But in 1788 on Guam, Luito and his people were well received. Commerce and communication with the southern islands was by that time very much welcomed by the Spanish colonial authorities. Exchanges of goods and information took place, and Luito returned to Lamotrek with the intention of continuing the voyage and exchange on a yearly basis. In the following year, 1789, they returned to Guam, this time in four canoes.

They never reached home. It is believed that they may have been caught in a storm and perished. Because they didn’t return to their islands, the people of Lamotrek and nearby islands thought that Guam was still an unsafe destination. The route was discontinued again.

Re-establishment

In 1804, a ship from Boston, the María, sailed from Guam towards the central Carolines in search of a cargo of sea cucumber, also called trepang or balate. They were joined by Captain Luis de Torres, a senior Chamorro-Spanish official who wanted to find out what had happened to Luito and the prospective annual visits. In Woleai, Torres was told that the Woleaians had naturally assumed that the Spaniards may have killed or detained them. Torres explained what was thought to have happened, after which it was agreed that visits would be made to Guam every year, and these were consequently maintained up to the twentieth century.

As for the colonial administration, communication between the Carolines and the Marianas were increased during the last decades of the nineteenth century by means of the regular mail ships that sailed a triangular route from the Philippines to Yap to Guam and back to the Philippines once every three months. In this case, the colonial agenda did contribute to local dynamics that had existed in the region for thousands of years, such as the contacts between the inhabitants of the different archipelagos.

For further reading

Barratt, Glynn. The Chamorros of the Mariana Islands: The Early European Records, 1521-1721. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

Hanlon, David. “Patterns of Colonial Rule in Micronesia.” In Tides of History: The Pacific Islands in the Twentieth Century. Edited by K.R. Howe, Robert C. Kiste, and Brij V. Lal. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1994.

Spate, O.H.K. The Spanish Lake: The Pacific Since Magellan. Vol. 1. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1979.