Though the Chamorro language was spoken by the people of the Marianas long before European expeditions made their way to the Pacific, its written form is still relatively new, with the most significant efforts toward standardization emerging only within the last fifty years. The need to adopt a standard spelling system for written Chamorro increased as the use of English became more prevalent. In Guam, the imposition of the English language came with the onset of American rule after Spain ceded the island to the United States in 1898.

In 1917 the US Naval Administration, under Governor Roy C. Smith, issued an order designating English as the official language, and banned the use of Chamorro except for official interpretations. In 1922 the naval administration instituted more drastic measures to eradicate the use of Chamorro within the school system, collecting and burning many of the Chamorro-English dictionaries that remained from the Spanish period.

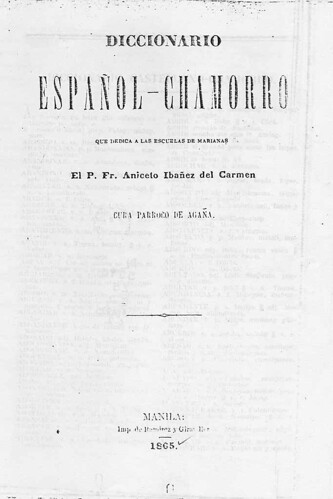

Through this systematic erosion of the Chamorro language, the use of English over Chamorro occurred earlier and more rapidly in Guam than in Saipan and the other Mariana Islands, the latter of which did not relinquish the use of Chamorro within its educational system until the 1960s. Until World War II, Saipan taught written Chamorro in its schools, using the grammatical conventions established by Father Aniceto Ibanez del Carmen in his 1865 Spanish-Chamorro dictionary.

As literacy increased in post-war Guam and the Marianas, efforts were made to develop a standardized spelling system for a language that had until then been contained within the oral tradition. Mirroring the trend of many Asian and Pacific languages, the development of a systematic spelling system in the Mariana Islands began in the 1960s with the establishment of the Marianas Orthography Committee. With its eight-member team comprising five members from Saipan, one from Rota, and two from Guam, the committee adopted the Marianas Orthography in January 1971. This orthography is reflected in the “Chamorro-English Dictionary” by Donald M. Topping, Pedro M. Ogo, and Bernadita C. Dungca, which was first published in 1975 and still remains the only current dictionary of its kind in print today.

The Marianas Orthography, which comprises twenty-one rules, became the basis for the orthography that was later developed in Guam by the Chamorro Language Commission. Mandated by public law to develop and adopt a standardized orthography for use within the government agencies, the Chamorro Language Commission of Guam adopted the official Chamorro Orthography in 1983.

Reorganized and modified, the orthography comprised seventeen rules, which eventually became codified into the Guam Administrative Rules. By 1993, the commission, in consultation with representatives from the CNMI, had modified the 1983 orthography and was preparing to formally submit a revised version for public adoption. However, as change is not without controversy, the commission membership was reorganized before such change could be implemented.

A significant development in the evolution of the written language, the Chamorro orthography, and the practical implications it had for the community, met with much resistance – which was expected by the commission. As pointed out in the orthography’s foreword, an orthography does not change how a language is used, but rather only specifies how it should be spelled in written form. But the move toward uniformity in the written format would necessarily entail changes to general practices.

Thus, as the commission gained prestige in the international community for its work in language policy, it also encountered opposition from many Chamorros in Guam who viewed the changes to the written language as an attack against the Chamorro culture. Challenges to the commission’s authority heightened in the early 1990s when, acting on its mandated authority as the Guam Place Name Commission, the commission presented for public review its proposed changes to Guam’s village names. The resulting circuit of public hearings roused many heated and emotional debates in the village communities, and the work of the commission by extension was not only staunchly rejected by many, but also publicly ridiculed.

By 1999, these challenges to the language commission’s authority culminated in the passage of Public Law 25-69, which dissolved the commission and created a new Department of Chamorro Affairs. While the law allotted for the transfer of the commission’s assets to the new entity, it did not transfer the commission’s previously mandated responsibilities. Repealing the laws that established and defined the role of the Chamorro Language Commission, the new law diffused the authority previously allotted to the Commission, incorporating some of its responsibilities into the framework of the new government agency. Among its effects, the law nullified the specific duty of the commission to review all Chamorro documents produced by government agencies to ensure conformity to the orthographical standards.

By 2005, this absence of a definitive language authority was evident in the passage of a law enacted ostensibly to enhance the protection of Guam’s marine resources. Among its provisions, Public Law 28-107 added a new section to the Guam code mandating that all Guam statutes and regulations reflect the updated spelling of specific Chamorro terms referenced in the law itself relative to game and fish.

Whether or not the spelling used in the law conforms to the adopted orthography is irrelevant; for the law references itself as its own authority, and not an external standard. The provision is a manifestation of the piecemeal approach to written standardization that has emerged in the absence of a recognized language authority that would oversee, monitor, and correct such usage in the public record.

Thus, though the 1983 Chamorro Orthography remains a matter of public record today, the incorporation of its standards in official usage is ultimately entirely voluntary. Developed as a means to preserving the language in light of the written tradition, such standards, as noted by the commission itself in the orthography, are rendered useless if not applied in practice. And without an official cohesive approach to ensuring the Chamorro language’s uniformity within public documents, it may take much longer for the impact of the orthography on the developing Chamorro written tradition to be fully realized.

For further reading

Guam Legislature. An Act Relative to the Duties of the Chamorro Language Commission, and for Other Purposes. Public Law 17-10. 17th Guam Legislature. 24 June 1983.

––– An Act Making General Appropriations for the Operation of the Executive and Judicial Branches of Government of Guam… Public Law 17-25. 17th Guam Legislature. 29 October 1983.

––– An Act to Repeal and Reenact § 19655 of the Government Code of Guam Relative to Creation and Use of the Tourist Attraction Fund, and for Other Purposes. Public Law 17-65. 17th Guam Legislature. 7 September 1984.

––– An Act to Repeal and Reenact §46107, Title 17, Guam Code Annotated, to Give the Chamorro Language Commission Authority in the Naming of Streets, Places, Buildings, and Facilities. Public Law 21-08. 21st Guam Legislature. 19 April 1991.

––– An Act to Amend §§ c of § 34.50, to Add a New §§ c to § 34.60, All of Title 9, Guam Code Annotated… Public Law 22-149. 22nd Guam Legislature. 19 December 1994.

––– An Act to Create the ‘Dipåttamenton i Kaohao Guinahan Chamorro,’ or ‘Department of Chamorro Affairs’. Public Law 25-69. 25th Guam Legislature. 8 July 1999.

Office of the Attorney General of Guam. Memorandum from the Attorney General. Ref. CLC 94-0767. 16 September 1994.

Supreme Court of Guam Compiler of Laws. “Chapter 7. Chamorro Orthography (Spelling Rule).” In Guam Administrative Rules and Regulations, Title 5A – Education. Last modified 24 July 2019.

Topping, Donald M. Chamorro Reference Grammar. With the assistance of Bernadita C. Dungca. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1973.

Topping, Donald M., Pedro M. Ogo, and Bernardita C. Dungca. Chamorro-English Dictionary. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1975.