CHamoru/Chamorro DNA Studies and the Origin of the CHamoru

Table of Contents

Share This

From where do the original inhabitants of the Marianas originate? How long ago did they first settle the islands? What kind of migration pattern describes the settlement or settlements of the Mariana Islands? These are some of the questions that researchers are trying to answer regarding the origins and relationships of the CHamoru/Chamorro people.

Miguel Vilar of the University of Pennsylvania is leading a team of scientists in collecting and analyzing DNA samples from modern CHamoru populations to trace the movement patterns and connections with other populations to discover what may have happened in the Marianas. While archeological evidence supports the idea that the Marianas may have been settled as early as 3,500 years ago by people from Island Southeast Asia (modern day Indonesia, the Philippines and Taiwan), there remain many questions about the genetic origins and gene flow of the CHamoru people.

Vilar’s research on CHamoru genetics builds on previous research conducted by JK (Koji) Lum into mitochondrial DNA. While most of the “stuff of heredity” (DNA) is found in the nucleus of our cells, the mitochondrion – responsible for cellular respiration or energy production – also contains DNA. Known as mitochondrial DNA, or mtDNA, this genetic material is remarkable in that it is passed through the maternal, or mother’s, line. Since sperm cells do not contribute mitochondria during fertilization, daughters and sons inherit mtDNA exclusively from their mothers, and only daughters can pass it on to the next generation.

This current research is part of National Geographic’s Genographic Project, an effort to work with indigenous communities worldwide and analyze DNA to answer questions about human origins and to understand how humans populated the earth. Vilar, one of the managers of the project, is working on collecting and analyzing samples of CHamoru male lineages to complement the work he has already done on female blood lines.

DNA and gene flow

DNA is short for deoxyribonucleic acid, the molecule that carries the information and instructions for the development and functioning of an organism. DNA is found in nearly every cell of the human body and is responsible for the unique characteristics each human being possesses. The genetic information contained in a person’s DNA is hereditary, meaning it is passed down from one generation to the next.

DNA is a long strand that has a characteristic “double helix” shape, like a twisted ladder. Most of it is found in the nucleus, a specific structure inside a cell that is surrounded by a membrane. When a cell is ready to divide, the DNA makes a copy of itself, and coils up into a bar-shaped form called a chromosome. Because of the extra copy, the chromosome looks like an “X;” each leg of the “X” is called a chromatid. When the cell divides, the chromosomes separate, with each new cell receiving an identical copy of the chromosome. The resulting daughter cells are genetically identical.

Chromosomes vary in number and shape among different organisms. Most species are generally characterized by having a specific number of chromosomes. For example, mosquitoes have 6, dogs have 78, an amoeba has 12, and shrimp have 254. In some organisms, chromosomes occur in pairs. These are called homologous chromosomes or homologues–they are not identical, but carry the same type of information. Human beings, for example, have 23 pairs of homologous chromosomes for a total of 46. Muscle cells, skin cells, nerve cells and other body cells have 46 chromosomes. Chromosomes carry information for traits like hair color, eye color, height, skin tone, etc., as directed by DNA.

However, sex cells – eggs and sperm which are used in reproduction – only have half the number of chromosomes, or 23. The parents of an individual contribute one of each pair of homologous chromosomes to bring the number of chromosomes back up to 23 pairs (46 in total). Twenty-two of the chromosome pairs are called autosomes. The sex chromosomes, labeled “X” or “Y,” determine the sex of the offspring. Females inherit an “X” chromosome from both the mother and father, while males inherit an “X” chromosome from the mother and a “Y” chromosome from the father. Females do not have a “Y” chromosome. Therefore, the “Y” chromosome is only passed on through the paternal or father’s line.

When sex cells form, their genetic information can undergo changes in a process known as “crossing over.” Here, pieces of DNA may move from one homologue to another, resulting in new variations of genetic material. This explains, in part, why siblings who have the same parents would be genetically and physically different from each other.

Because of the variations in genetic material that occur during reproduction, it is possible to map the movement of certain kinds of genes (and the characteristics they code for) among populations. Gene flow is the movement of genes from one population to another. Scientists measure the frequency certain kinds of genes appear in a given population. This is how they determine if a gene (or a population that carries the gene) has moved from one place to another. Most often, scientists look for changes in DNA, or mutations, because these stand out and are easier to track.

Research questions in relation to previous studies

An early study of CHamoru genetics in 1967 by CC Plato and M. Cruz, and in 1998 by JK Lum and RL Cann, demonstrated that CHamorus are distinctive in relation to neighboring Micronesian populations. The Lum and Cann study reported that more than 85 percent of the CHamorus studied belong to mtDNA haplogroups E1 and E2, which are relatively common in populations from Island Southeast Asia, but rare in other groups of Pacific islands. Most of the remaining CHamoru lineage groups belong to a unique haplogroup labeled B4a1a1a, which is common in Island Southeast Asia and Melanesia. Haplogroup B4a1a1a is also the most common group in Central and Eastern Micronesia and Polynesia, and is called the “Polynesia Motif.”

The term “haplogroup” refers to a specific genetic population that shares a common ancestor directly from their maternal or paternal lines. They are usually designated by letters of the alphabet and numbers to indicate more specific haplogroups. The most common changes in DNA that scientists look at for each haplogroup are genetic markers known as “SNPs” or “single nucleotide polymorphisms,” which occur naturally over time. When an SNP occurs, it becomes a marker that can be passed on from one generation to the next. Humans who descend from the same genetic line will share a common SNP. Haplogroup lineages can then be mapped out like a tree, showing more diversity over time through the various branches that emerge.

The fundamental research question that the Vilar group is trying to answer is whether CHamorus are the direct descendants of a single migration from Island Southeast Asia around 4,000 years ago, or the descendants of a second wave of migrations from Island Southeast Asia about 1,000 years ago. The question arises from an understanding of the two distinct periods of Marianas history – the pre-Latte Era and the Latte Era. The Vilar team is also interested in finding if the CHamoru gene pool shows evidence of gene flow from neighboring islands.

Archeological evidence points to settlement of the Marianas as early as 3,600 years ago, and the appearance of a unique clay pottery style, referred to as Marianas redware. Marianas redware shows similarities with other pottery styles of the same period in Southeast Asia and what is known as the Lapita Cultural Complex. But while Lapita pottery is widely dispersed throughout Eastern Melanesia, Polynesia and Central-Eastern Micronesia, Marianas redware is unique to the Mariana Islands.

Unique to the Mariana Islands (in relation to all other islands of the “remote” Pacific) is rice cultivation, and utterly unique to the Marianas is the construction of latte, large stone columns with hemisphere-shaped capstones. However, both rice cultivation and latte construction do not appear until the Latte Era, beginning about 1,000 years ago. Genetic study of modern CHamorus may provide clues to test competing theories as to whether Latte Era people are descendants of earlier pre-Latte people, or are largely descended from a second migration wave, which brought latte technology and rice agriculture to these islands.

Genetic findings regarding distinctiveness of CHamorus in the Mariana Islands

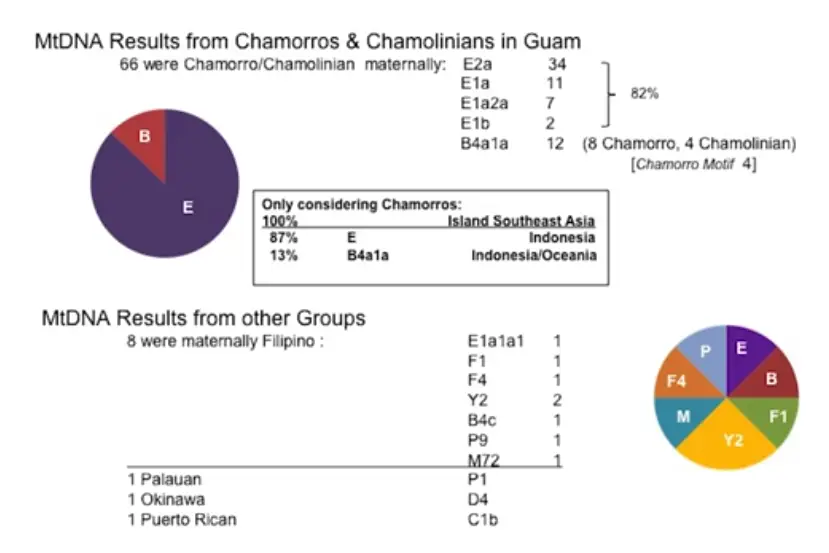

Vilar’s research team analyzed blood and tissue samples of 105 self-identified CHamoru volunteers and 17 Saipan islanders with Carolinian ancestry on their mother’s side. They also reassessed the 210 samples from neighboring islands collected during the Lum and Cann study, but with additional information. The scientists also analyzed the complete mtDNA of 32 individual CHamorus.

Vilar’s team found limited genetic diversity among the lineages of the CHamoru subjects. The 122 individuals tested in the sample population together showed 19 unique haplotypes (groups of traits inherited together), while the 105 Chamorros showed 14 haplotypes. The CHamoru group also shared mtDNA mutations characteristic of the E1 and E2 haplogroups, which none of the 17 individuals with Carolinian ancestry showed. About 65 percent of the CHamoru individuals had the E2 haplogroup; the low frequency of variations resembled the pattern seen in a young expanding population. About 28 percent of the CHamoru lineages belonged to the E1 haplogroup, which also resembled a young expanding population.

Analysis of the specific E1 and E2 haplogroups of the CHamorus showed they were not present outside the Mariana Islands. This pattern indicates that a founder effect occurred. A founder effect is when an original founding population arrives, becomes isolated, and over time, results in a new population that has only a small amount of the genetic variation seen in the original population. In the Marianas, the founding E1 and E2 haplogroup lineages arrived from Island Southeast Asia around 4,000 years ago and after 3,500 years in isolation, the two lineages acquired the mutations that gave rise to the unique genetic lineage seen in the Marianas. The scientists also believe the initial arrival of the Marianas population may have occurred even earlier, maybe 5,000 years ago.

The B4 haplogroup was found in only 8 percent of the CHamoru lineages, but 100 percent of the individuals with Carolinian ancestry. Most of the Saipan Carolinians in the sample shared a particular B4a1a1a lineage, but another B4a1a1a lineage with a specific mutation known as C16114T was revealed only in CHamorus on Guam and Rota.

Analysis of the 32 complete mtDNA samples also pointed out the uniqueness of the lineages found in the CHamoru individuals. Like the E1 and E2 haplogroups, the CHamoru mtDNA of the Marianas is found only in these islands, but shows strong links to Island Southeast Asia that possibly date back 4,000-5,000 years ago.

The uniqueness of the B4 haplogroups with the C16114T mutation suggests that this lineage is a recent introduction to the Marianas. Perhaps a second migration occurred, bringing knowledge of rice cultivation and latte technology to the islands about 1,000 years ago. However, the Vilar research team also suggests the possibility that the B4 haplogroup may have arrived from neighboring Micronesian islands sometime in the last 2,000 years, and the mutation may have been acquired in the Marianas.

The limited genetic diversity is consistent with the depopulation of the Marianas which occurred with the arrival and conquest by the Spanish in the 17th century. The Spanish colonial policy of reducción resulted in the forced removal of the native population of the northern islands (except Rota) and the northern villages of Guam. The people were placed into districts organized by the Spanish in central and southern Guam. The northern islands remained empty until they were repopulated by Caroline Islanders in the early 1800s; CHamorus finally were allowed to move back several decades later. There is also evidence of gene flow: people from Saipan of Carolinian ancestry today share lineages with other Caroline islanders and not with Guam or Rota or other CHamorus from Saipan. This is possibly from the resettlement by Caroline islanders. Meanwhile, the E1 and E2 haplogroups of CHamorus in Saipan may reflect the movement of CHamorus from Guam and Rota back to Saipan in the mid-1800s.

Vilar's research on CHamoru male lineages

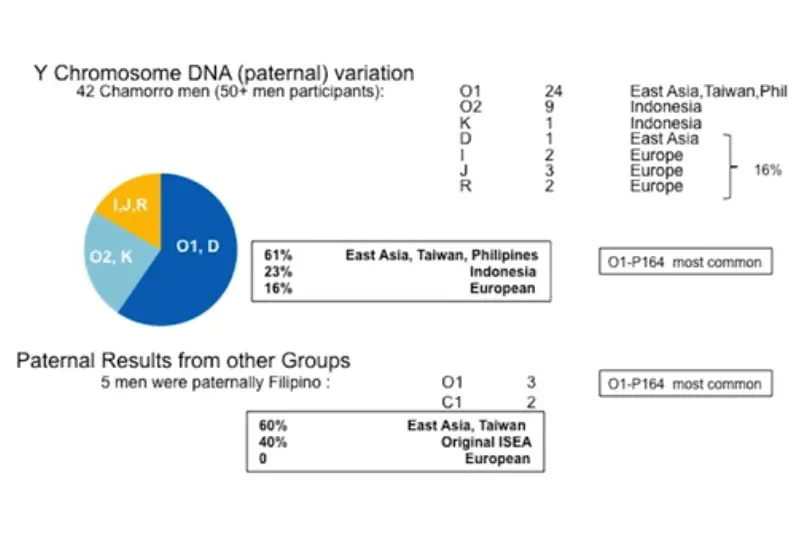

Dr. Vilar is currently (as of 2013) conducting research that focuses on Y-Chromosome DNA from male lineages, as well as carrying out a particular type of analysis using DNA inherited from both male and female lines, known as autosomal STR analysis. He expects to measure the magnitude of gene flow from Spanish, Mexican and Filipino populations that settled on Guam during the Spanish administration (1668-1898). Such determination of “mixture” could not be revealed by mtDNA studies, owing to male “bias” regarding mating and intermarriage, which largely involved foreign men with CHamoru women, in turn, related to the island’s transition into a male dominated society under Spanish colonialism.

Vilar’s research brought him to Guam in August and September 2013 when he participated in the 2nd Marianas History Conference and presented his findings on female lineages which he published in 2012. In an interview with the Pacific Daily News, Vilar expressed that while he expects to find mixtures of Spanish, Mexican and Filipino genes, he also suspects that he will see a “retaining of this ancestral, indigenous [CHamoru] Y-chromosome,” but how much of that Y-chromosome still exists in the current population is uncertain.

Conclusions of the 2013 study

- The analysis of the 2013 data is not yet complete.

- The mtDNA data supports the earlier work that all CHamoru mtDNA lineages are (100%) of Island Southeast Asia origin, that origin is likely in Eastern Indonesia.

- The mtDNA signature of CHamoru is unique.

- The Y-DNA data also suggests a strong connection to Island Southeast Asia, and supports the proposed linguistic hypothesis of Out of Taiwan origin of Austronesian languages.

- The diversity of CHamoru Y-DNA lineages suggests the majority of lineages (60-70%) are prehistoric, however some have a historic origin (Europe, Philippines).

- The biogeographical component date supports the theory of an origin in Island Southeast Asia, with recent admixture from Europe (in all CHamoru participants). The surprising Native American admixture is historic, likely arising from hundreds of Mexican workers arriving in and integrating into the Marianas during the Spanish colonization.

Results of the 2013 study

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (passed on through females):

Analysis of Y Chromosome DNA (passed on through males):

Biogeographic components of CHamorus

On average, CHamorus were:

43% (+/- 4%) Northeast Asian

29% (+/- 3%) Southeast Asian

4% (+/- 1.5%) Oceania

10% (+/- 3.5%) Mediterranean

7% (+/- 2.5%) Northern European

3% (+/- 1%) Southwestern Asian

3% (+/- 1.5%) Native American

For comparison, Filipinos were:

56% (+/- 1%) Northeast Asian

36% (+/- 1%) Southeast Asian

5% (+/- 1%) Oceania

1.5% (+/- 1.5%) Mediterranean

The ratio of NE Asian, SE Asian, Oceania from CHamorus and Filipinos is the same, yet variation (standard deviation) is higher for CHamorus.

Also, the standard deviation of the European and Native American components is much higher than that of the NE Asian and SE Asian components. This indicates that the former are much more recent – i.e. historical instead of prehistorical – additions to CHamoru genotype. This is because, over time, the genetic information spreads through and stabilizes within a population, reducing the amount of deviation.

Origin of Y-DNA haplogroup 01-P164

Haplogroup O1-P164, showing quite a bit of diversity, was found in 20 CHamorus (48 percent of CHamoru men). It was found in men with eight different surnames: Camacho, Reyes, Molani, Cepeda, Sablan, Aguon, Flores, and Martinez.

Haplogroup O1-P164, also very diverse, was found in three Filipinos (60 percent of Filipino participants), who also had distinct surnames.

The diversity of surnames is notable, because they, just as the Y chromosomes, are passed on through males.

So, given the genetic diversity (which correlates to the amount of time the DNA has spent mutating) and the diversity in surnames, the lineage is likely old and prehistoric among CHamorus. Further analysis and research of historical documents regarding surnames is needed.

Previous academic papers on Y-DNA from Island Southeast Asia suggest that O1-P164 originated in China and then moved through Taiwan, the Philippines and Indonesia with the spread of Austronesian languages (5,000-4,000 Before Present), supporting the Out of Taiwan hypothesis.

Rare O1 haplotypes, such as O1-F18 and O1-F742, may be Filipino.

Origin of other CHamoru Y-DNA lineages

O2-F140 was found in four CHamorus and O2-F3288 was found in two CHamorus. Both lineages were associated with the last name Cruz.

Previous papers on Y-DNA from Island Southeast Asia suggest that O2 originated in mainland Southeast Asia and may have arrived through Western Indonesia. But it also occurs in Filipinos and even Taiwanese, so it could be associated with the Austronesian Expansion. Further analysis and consideration of historical documents will help.

K was found in one CHamoru. Haplogroup K is very old (45,000 years before present), and it’s associated with the earliest settlers to reach Island Southeast Asia.

Editor’s note: Guampedia thanks Dr. Gary M. Heathcote for his kind assistance in completing this entry. 2013 additions by Eric Vincent Thomas.

For further reading

Lum, J. Koji, and Rebecca L. Cann. “mtDNA and Language Support a Common Origin of Micronesians and Polynesians in Island Southeast Asia.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 105, no. 2 (1998): 109-119.

–––. “mtDNA Lineage Analyses: Origins and Migrations of Micronesians and Polynesians.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 113, no. 2 (2000): 151-168.

Miculka, Cameron. “History Written in Chamorro DNA: National Geographic Project Seeks to Trace Migration.” Pacific Daily News, 14 October 2013.

Plato, Chris C., and MT Cruz. “Blood Groups and Haptoglobin Frequencies of the Chamorros of Guam.” American Journal of Human Genetics 19, no. 6 (1967): 722-731.

Vilar, Miguel G., Chim W. Chan, Dana R. Santos, Daniel Lynch, Rita Spathis, Ralph M. Garruto, and J. Koji Lum. “The Origins and Genetic Distinctiveness of the Chamorros of the Mariana Islands: An mtDNA Perspective.” American Journal of Human Biology 25, no. 1 (2013): 116-122.