Celebration of the finakpo’

Although death is an occasion for grief, the CHamorus consider it as a chance for the extended family throughout the island to gather and pray for the repose of the spirit of the difunto, or deceased male, or difunta, or deceased female. This practice dates back to the ancient CHamoru belief system of ancestral worship. The CHamorus believed that the family was so important that family members could affect them even in death. When a family member died, CHamorus would spend days wailing and chanting until a celebration was held to rejoice the spirit’s journey hulo’ gi långet. Långet means sky, but it also means heaven.

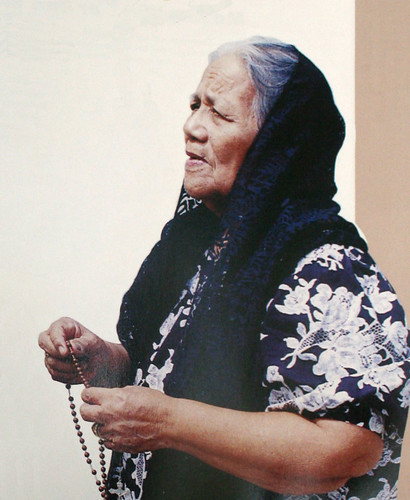

Today, aspects of these practices remain. For example – the nine days of lisåyon måtai, or rosary for the dead, followed by another nine days of lisåyon familia, or the immediate family rosary and followed a year later by the lisayon komple’åños, or anniversary rosary. These prayer groups exemplify the early CHamorus’ show of respect given to the their deceased members over extended time. They are reminiscent of the intense wailing and chanting over the death of a clan member over a period of time. Even the manner in which the techa, (prayer leader) says the prayer, exemplifies the loud wailing of the clan chant leader. Today, the techa who can singsong the rosary the loudest is the most coveted candidate for the job.

When a person is chachafflek (near death) members of the family begin to arrive at the home, or at the hospital, to await the death of the family member. A priest would be notified to give the olios (last rites). Immediately, upon death, a lisåyu, or rosary begins, usually led by a techa or an elder.

The lisåyu would continue for nine days at the difunto’s or difunta’s home or at the village church. The ninth day may end before or after the funeral. Gatherings are solemn and sorrowful; people are usually served light refreshments each night and a dinner at the end of the ninth day, an occasion in which members of the familia give small nina’i’-nengkanno’, fina’mames yan gimen (food, sweets and drinks). Traditional practice calls for nine days of public rosary and nine days for the family.

Bela, or overnight wakes, were held at the home of the difunta or difunto. Today, instead of a bela, most families use the church for several hours to allow families and friends to pay their respect on the day of the funeral.

Bela in the early days was held overnight and throughout the next day until the burial procession took the body to the church for the mass and responso. In the past, family and mourners walked the procession to the simenteyu (cemetery). Homes situated along the route of the procession would light candles on their window sills as the carriage carrying the deceased passed by. Today, a caravan of cars takes the deceased to the burial site.

During a bela, people from throughout the island would arrive to pray and give ika – a form of chenchule’ for the dead. Ika is usually given in greater amount than a wedding chenchule’, because families plan for a wedding but not for a funeral.

Mourning for the difunto or difunta continued for a year. The members of the family would wear black until after the komple’años (anniversary mass) is celebrated. They avoided parties, singing and dancing, and other social activities. The widow or the widower, as the case may be, would not consider remarriage until after the one-year mourning period.

The celebration of the finakpo’ or the komple’åños, was elaborate and joyful. Specially prepared foods and fina’mames are served. Delicacies (See CHamoru recipes here) may include apigige’, leche flan, åhu,guihan (fish), ayuyu (coconut crab), haggan (turtle), fanihi (fruit bat), hinetnon babui yan kåtne (roasted pig and meat). The extended family would prepare and host this occasion to show its appreciation to those who had attended the finatai, and for participating in the prayer groups. It was also given as a form of reciprocity to those who had given their assistance to the bereaved family in whatever form.

Many of these traditions continue today.

Editor’s note: This entry was adapted and reprinted with permission from ”Cultural Traditions,” from the Hale’-ta Series, Department of CHamoru Affairs, Government of Guam.