How early people chose their home

White sandy beaches, lush jungles, verdant landscapes and gorgeous sunsets—the Marianas, for many, resemble a tropical paradise. With all this natural beauty, do you ever wonder why some parts of Guam are more crowded than others? The villages on Guam with the largest populations are in the northern and central parts of the island, including Dededo, Yigo, Tamuning/Tumon, Barrigada, and Mangilao. The southern village of Hågat/Agat also has a substantial population. The landscape around each of these villages varies, from the large, relatively flat limestone plateau in the north, to the rolling hills and grasslands of the south. The interior of the island has dense jungles and vegetation. So, how do Guam residents decide where they live? Why are some villages more populated than others? What does this pattern of residence suggest about modern Guam society?

Archeologists wonder about settlement patterns of ancient societies. How did people from ancient cultures decide where they would settle? What factors played a role? How did they adapt to their surroundings? How did ancient settlement patterns change and under what conditions? The term “settlement pattern” refers to the ways in which a population inhabits or functions within a particular area or environment, given the specific conditions that are present. A study of settlement patterns examines the range of activities a society participates in and observes how populations interact with the natural environment. These patterns are interesting because they reflect cultural traditions, beliefs and other social practices. They demonstrate how people adapt and use available resources, as well as how they face challenges and limitations in order to survive.

When European explorers first ventured into the wide Pacific Ocean, they were surprised to find that many of the islands were already inhabited. Indeed, archeologists who have studied the Marianas believe that people were living in this island chain for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. Although there is no single model to explain human settlement patterns for the whole of the Mariana Islands, archeological work done on Guam provides some insight into how the earliest inhabitants probably made their homes in the islands.

Geological overview

Just over 1,200 miles east of the Philippines, the Mariana Islands is an archipelago comprised of 15 islands that run north to south, extending from about 20° north latitude and 143° east longitude, to 13° north latitude and 142° east longitude. The islands lie on the western edge of the Marianas Trench, the deepest trench in the Pacific Ocean, where the Pacific and Philippine plates meet. This area experiences a lot of tectonic activity, including volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. The islands have a warm, humid tropical climate with seasonal patterns of rain and dry over the course of a year. During the dry season, which runs from January to May, there is little rainfall but strong easterly trade winds blow across the region. The wet or rainy season runs from June to December and is characterized by frequent rainstorms and occasional typhoons.

The northernmost islands of the archipelago are younger than the larger islands in the south, and some have active volcanoes. These northern islands lack fringing reefs and because of the steep terrain, they have little fresh water. On the other hand, the southern islands, namely Saipan, Tinian, Rota and Guam, have extensive areas of flat land, and, with the exception of Rota, have large lagoons surrounded by fringing reefs. Fresh water is available from scattered small springs and seeps. Guam also has several small rivers and streams of fresh water. Archeological evidence suggests that these southern islands were the first to be settled, as they are larger and more hospitable than the smaller rugged islands to the north. Most likely, all four of these islands were settled relatively quickly and at roughly the same time. Although the smaller islands to the north lack flat lands and protected waters they probably were visited occasionally for fishing and foraging expeditions throughout prehistory.

The dense vegetation in the southern Marianas consists of trees and plants that are both native to the islands, and other species that have been introduced over the last 4000 years of human occupation. Most of the native plants are suited to live in the tropics, including salt-tolerant species like zebrawood (panao), rosewood (banalo), wild hibiscus (pago) and pandanus (kafu), and others that are able to withstand the occasional periods of heavy rain and drought that characterize this part of Micronesia, such as Federico palm (fadang) and seeded breadfruit (dugdug). The northern islands, however, have less diverse vegetation, and some of the islands with active volcanoes do not have much vegetation at all. Many of the introduced species are food plants, such as seedless breadfruit, sugar cane, rice, yam, taro, bananas and betel nut (Russell 1998).

There is also an abundance of marine animals, many of which were used for food by the ancient CHamorus. The surrounding reefs and lagoons also contained different kinds of shellfish, which could be eaten and their shells used for making tools. The relative isolation of the Marianas allowed for a variety of sea birds but only two kinds of land mammals to inhabit the islands. Nevertheless, the original settlers found these islands habitable, and over time, developed a culture well adapted to life in small tropical communities.

Guam, southernmost in the Marianas

Guam is formed largely of volcanic rock and limestone, surrounded closely by a large fringing reef. The reef has a few breaks to create the bays in the south like Humåtak and Cetti, and extends further out to Cocos Island off the coast of Merizo (Malesso’). The northern half is primarily limestone on top of a submerged volcano, while the southern half is largely volcanic basalt rock with some areas of limestone. The northern plateau gradually slopes to an elevation of over 500 feet above sea level on the east and about 200-400 feet above sea level on the west. The edges of this part of the island have steep cliffs and limestone forests, and small beaches with fine sand. There are no rivers in the northern plateau. Central Guam, from Pago Bay to Hagåtña Bay, is comprised largely of swamps and small river valleys with rich vegetation among low hills. In contrast, the southern part of the island is mountainous, with numerous small rivers that drain into Fena or Talofofo Rivers to the east. Much of the land is grassland or savannah. The highest elevation point is over 1300 feet above sea level (Reed 1952).

First settlements

The peopling of the Pacific has always intrigued archeologists who try to piece together the story of how humans managed to make their way across vast ocean spaces and create such complex societies on tiny, isolated and dispersed islands. The Marianas are particularly significant because this island chain was probably one of the earliest to be settled by humans. Although we can never know what motivated or drove the people who eventually settled in the Marianas to leave their homelands to claim new lands, archeologists have tried to reconstruct what these early Pacific voyagers might have been like.

Some archeologists suggest that the original voyagers who went to the Marianas were Austronesians who purposefully sought out new places to colonize. Sailing from Southeast Asia or from the Philippines, they must have possessed adequate knowledge of wind and current patterns to be able to navigate vast open ocean spaces. Their technology likely included outrigger canoes. These first settlers had a mixed economy, including horticulture for the cultivation of different food plants, and fishing. They were also skilled at making pottery. Based on archeological evidence, the settling of Micronesia was a “two-pronged” event, with the western high islands of the Marianas, Palau and Yap being settled first, maybe as early as 4,000 years ago. However, there is no archeological evidence to support the idea that the people who settled Palau and the Marianas originated from the same place. Also, whether these voyagers came in large numbers all at once or if a more gradual movement of people took place, it is not possible to say. In any case, the people who landed in the Marianas decided to stay and do not seem to have ventured or settled farther than these islands. And so, the more remote islands in Micronesia remained uninhabited until the next wave of ocean voyagers settled the Eastern Caroline and the Marshalls Islands some 2,000 years later.

According to archeological evidence, the landscape of the Mariana Islands 4,000 years ago was quite different than it is today. Apparently, there were more embayments (bays) and estuaries, providing rich environments for procuring fish and shellfish. Although debatable, some archeologists propose that with such abundance, the first peoples probably chose the coastal regions to settle first. However, about 3,000 years ago, the coastal regions underwent significant geological change. Changing sea levels and tectonic uplifting caused the small ancient beaches to shift inland, while producing sandpits that eventually filled in with sediment to form wetlands and newer beaches. This would explain why some of the older settlements are found in excavations several feet inland, away from the current beach or coastline, and underneath layers of debris from later occupations.

The first settlements in the Marianas consisted of small, scattered populations, who most likely used natural wood and plant materials to construct their residences; unfortunately, these materials do not preserve well in the tropical climate. Some archeologists suggest that the initial coastal settlements were comprised of a handful (maybe ten or twenty) of different pole and thatch structures, possibly resting on wooden posts, and arranged next to embayments and shorelines for quick and easy access to fishing areas. Caves and rock shelters may also have been occupied, especially for protection during times of inclement weather like typhoons, or temporarily used for hunting and fishing expeditions. Some of the early occupation sites include Tarague and Ritidian in Guam, Achugao, Laulau and Chalan Piao in Saipan, Unai Chulu in Tinian, and Mochong in Rota.

Archeologists refer to the period of initial settlement and the emergence of early CHamoru culture as the Pre-Latte Phase or Era, and archeological evidence indicates that the occupants of these early sites shared the same culture. It is likely that ancient Marianas populations were organized loosely as family groups with little or no social stratification—in other words, no distinct social classes, as seen later in Latte Era CHamoru society. Using stone and shell tools they cleared land to cultivate food plants they introduced. The abundance of marine animals in the protected lagoons, reefs and open ocean provided most of their dietary protein and made up for the lack of domesticated land mammals.

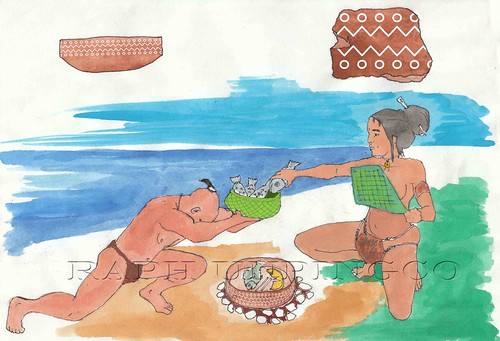

Although scattered, the early populations in the Marianas likely maintained frequent contact with each other, intermarrying, trading, visiting and moving residences. They traveled between islands, procuring resources for food and tool manufacture. The early pottery forms found throughout the islands during the Pre-Latte Phase attests to the uniformity of the culture in the Marianas. Small, thin-walled vessels with lime-incised decorations, the size and shape of ancient Marianas pottery, known as Early Calcareous Ware, was ideal for a mobile society. These light-weight pots were portable and easily carried small amounts of food or water for people on the move.

Because of the vulnerability of the Marianas to frequent storms and periods of drought, Pre-Latte gardens and plots were likely dispersed over large areas, rather than situated in just a few locations, to ensure some food resources would survive when environmental conditions were harsh. The Pre-Latte peoples probably dried much of their food as well for easy storage and transport. As populations grew, they began to use resources found further inland. By using what could be found in the valleys and jungles, in addition to marine resources, they were able to accommodate and feed more people. Soon, other important changes followed.

Early settlements and culture change

All cultures change. People develop new ways of doing things as they adapt to their surroundings. Changes in population often necessitate changes in culture and society as well. Very likely, an increase in population size and density drove the need for the ancestral CHamorus to expand their settlements and adapt. Modifications in pottery forms and styles of the ancient CHamorus provide some evidence for societal and culture change.

As stated previously, the early pottery styles of the Pre-Latte Phase were thin, small vessels that were easy to carry and to transport small quantities of food and water from one place to another. Such portable vessels were ideal for fishing and foraging societies constantly on the move to find food. By 2,000 years ago, changes in pottery forms began to appear, with the production of large, flat-bottomed vessels more suited for grilling or cooking. These containers were heavy and less portable than previous pots, possibly showing a change in subsistence style or diet. The heavier ceramics could also indicate that settlements were becoming more permanent.

Archeologists suggest the population at this time was relying more on cultivated plants than marine resources and so needed land for planting and processing a wider variety of foods. Consequently, ancient CHamorus would have to develop rules and systems for securing access to arable land, productive fishing grounds and foraging areas. For example, they possibly began to establish rituals and sanctions to limit or restrict fishing to particular individuals or during certain times of the year. They also may have developed techniques to prevent over-harvesting of soils and garden plots. These adaptations may have helped the early CHamorus to face the increasing environmental pressure and challenges of feeding a larger population.

With families competing for land, rules regarding inheritance had to be instituted. Social stratification or division likewise might have increased, as families and lineages were ranked by wealth or other cultural attributes. Ancient CHamoru society was organizing itself into clans and villages, who competed with each other to gain prestige and access to productive environmental resources. In addition, strategies to form and shift alliances through marriage, ritual warfare and reciprocal gift-giving emerged. These adaptations eventually became a part of the culture and society encountered by 16th century Europeans at their arrival in the Marianas.

Latte Era settlements

By 1,000 years ago, a new series of changes appears in the archeological record. The distinctive feature of this phase in Marianas history is the large stone structures known as latte. These stone pillars, with their large bases and capstones indicated a remarkable shift in CHamoru culture, architecture and settlement.

During the Latte Era, the ancient CHamorus continued to occupy ideal coastal settlements characterized by numerous structures with easy access to fishing grounds. However, as populations became too large, some people began to live in less desirable coastal sites, or in inland villages, farther away from the ocean and its resources. More permanent settlements also began to appear in the small rugged islands north of Saipan and the little island of Aguigan off the southern coast of Tinian.

The increase in population also presented challenges for procuring adequate food resources. As a result, the CHamorus came up with more specialized fishing methods and tools, including a variety of nets, compound fishhooks, sinkers and chumming devices. These innovations allowed greater catches with minimal increases in labor.

They also began to rely more on starches and cultivated plants, clearing more land for farming and developing tools for the processing and cooking of tubers, roots and other plant foods. Pottery became larger and thicker for boiling, steaming and cooking, as well as for storing greater amounts of food and rainwater. Scrapers and peelers, knives and other hand tools for cleaning fish and vegetables were manufactured. Large basalt and limestone mortars and pestles to husk rice or process herbs and cycad nuts also appeared in the Latte Phase.

Population increases may have also led to a more stratified, though not necessarily rigid, social structure, with the emergence of at least two social castes—the upper caste chamorri and the lower caste mangachang. The chamorri presumably had control over land and other natural resources, and granted limited access to the mangachang to areas for farming. A matrilineal kinship system of inheritance organized the population into clans, which became the important economic and social unit of ancient CHamoru society. Living in scattered autonomous villages throughout the islands, these clans vied with each other through ritual warfare and reciprocal gift giving to increase their social status as well as to maintain political alliances.

The construction of latte architecture, and of larger scale villages and residences also occurred during the Latte Era. Archeologists believe latte to be foundational posts for large public houses like the bachelor men’s houses (guma’ uritao), canoe houses and residences. Arranged in parallel rows, the materials for the latte stones were quarried from volcanic rock and limestone, and in some instances, large coral heads carried from the shore were used for capstones. Latte structures may also have been used as symbols of clan strength and status based on their size, as well as to demarcate territorial clan lands and fishing grounds. Coastal latte villages had more than 100 houses or structures, whereas inland latte villages may have numbered only about ten to twenty houses. It seems likely, therefore, that coastal latte sites represent areas that experienced longer, more intense occupation than latte sites found in the interior of the islands. It may also mean that interior latte villages were only temporarily or seasonally used, but this not confirmed archeologically.

Another interesting aspect of latte sets is their placement within latte villages. For example, archeological examination of coastal latte sets show that the long axis of latte was laid parallel to the sea, while inland latte sets were arranged along natural features like streams or cliffs. There is also variation in the staggering of latte sets and other non-latte residences. In Rota, for example, archeologists have suggested that non-latte residences, possibly occupied by low-ranking families, were located between latte residences or placed further inland, while cooking and storage areas were placed closer to the shore.

The material culture or artifacts and evidence of other features recovered from latte sites include pottery fragments, fire pits, earth ovens, placements for post holes, shell fragments and human burials. Some cave and rock shelters also have revealed pictographs and petroglyphs, the symbolic meanings of which have yet to be determined.

Well established long before Magellan

By the time the explorer Ferdinand Magellan landed in the Marianas in 1521, the CHamorus had already established permanent settlements on almost all of the islands in the archipelago. Some archeologists suggest the dramatic changes in culture and settlement patterns of the ancient CHamorus from the Pre-Latte and Latte Phases were most likely due to changes in environment, as well as by increasing populations and the need to procure enough food for more people.

Perhaps initial settlements in coastal sites where marine resources were abundant became overcrowded to the point that populations were forced to move to the interior of the islands. Periods of drought, volcanic activity and frequent typhoons could have made living in the Marianas precarious and at times, dangerous. Changing sea levels and tectonic plate activity, however, had altered the landscape enough over time to increase the amount of land available for cultivation. Technological innovations in tool manufacture and pottery, as well as shifts in subsistence methods and diet to include a greater reliance on plant foods, helped the ancient CHamorus to adapt and survive in this challenging environment. They organized themselves into distinct, socially stratified or ranked clans that used competition and a system of matrilineal kinship and inheritance to secure access to arable lands and fishing grounds. The longer they stayed, the more they developed the unique, complex culture recognized by other Pacific Islanders and Western explorers. The latte stones they built and left behind are continual reminders of the hardiness of the ancient CHamorus and their ancestors to settle and live in the Mariana Islands. In any case, more research needs to be conducted in this area to paint a clearer picture of early settlement patterns and cultural change.

For further reading

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation. An Overview of Northern Marianas Prehistory. By Rosalind L. Hunter-Anderson and Brian M. Butler. Micronesian Archaeological Survey, Report Number 31. Mangilao: MARS, 1995.

–––. Tiempon I Manmofo’na. Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. By Scott Russell. Micronesian Archaeological Survey No. 32. Saipan: CNMIHPO, 1998.

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Petersen, Glenn. Traditional Micronesian Societies: Adaptation, Integration, and Political Organization. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009.

US Department of the Interior National Park Service. General Report on Archeology and History of Guam. By Erik K. Reed. Sante Fe: NPS, 1952.