Family ties of key importance

In CHamoru culture today, the notion of family or i-familia is very important. From rosaries to weddings, funerals to barbecues, many CHamoru social events revolve around family. CHamoru names, social status, social and cultural identities are rooted in family relations. CHamorus rely on their families to take care of them; likewise, CHamorus are given responsibilities and obligations to carry out because of the connection they share as members of the same kin group.

Anthropologists study kinship in different cultures to learn about how people organize themselves into different social groups. In general, societies use kinship systems to group people based on degrees of relatedness through blood, marriage, or through other socially or culturally recognized rules. People often think of their immediate family relations, such as parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts and uncles, as their family. Kinship, though, also includes extended family members such as in-laws or cousins several times removed. The idea of kinship, then, is largely based on a culture’s idea of which relatives are counted as family.

The notion of kinship is crucial in small or traditional societies, like ancient CHamoru society, because it impacts all aspects of social life, from determining an individual’s personal identity, to designating where families live or reside, to instituting customs about land. Land tenure, another important anthropological concept, refers to the practices or socially recognized rules regarding access and inheritance of land, water, trees and other natural resources. Land tenure is organized around kinship systems and determines who gets to use certain fishing areas or farming lands.

Kinship also structures political alliances and connections between different kin groups or communities. For archeologists, kinship and land tenure are difficult to assess and analyze, and such studies often are left to cultural anthropologists. However, archeologists study settlement patterns and the structure of households and residences, as well as the spaces where families or related groups of people live and carry out their day-to-day activities. Artifacts, burials and structural remains may demonstrate rank, status or lineages that may be understood within the context of kin relations.

Unfortunately, not much has been written specifically about the archaeology of ancient CHamoru kinship or land tenure systems. Most of the available writings about notions of family, lineages and clan relationships or inheritance patterns instead are interpretations based on early historic accounts by missionaries and explorers, as well as comparisons with other Micronesian cultures. What follows are popular representations or interpretations of early CHamoru kinship and land tenure, which, obviously, are open for further research and debate.

Family structure

All societies have families. The family is basically an economic and social unit comprised of one or more parents and their children. As an economic unit, the members of the family labor and use their resources to support, feed and shelter each other. As a social unit, families meet social, cultural and emotional needs and desires.

Families, however, can take many forms, even within the same society. Members of the family have certain rights and obligations to each other. They may live in the same household, but that is not always the case — some members may live in separate households away from other relatives. In general, though, they take care of each other’s needs. Children are nurtured, protected and taught the values, practices and behaviors that are important for membership in the family and society.

The nuclear family is a concept that defines the immediate family of parents and children. Individuals, however, usually live within two nuclear families — the family in which one is born and raised, and the family one forms when he or she marries and has children. Many cultures share the idea of the nuclear family, but the extended family is a more universal concept and has more social importance among different cultural groups. An extended family includes parents and children, but is expanded to include generations, or siblings and their spouses and children. Often, an extended family consists of several families linked through a sibling tie; for example, two married brothers, their wives and their children may live together as one family unit. Extended families, not surprisingly, can be very large.

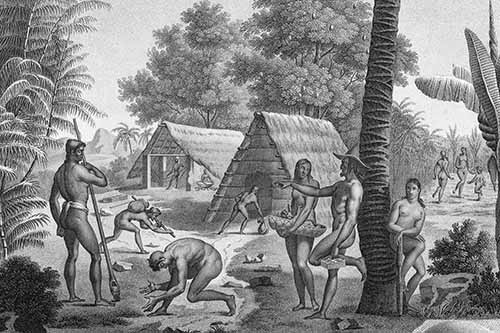

Ancient CHamoru society was organized as interdependent extended families that lived in close proximity to each other. The family as a whole was more important than its individual members. The family provided the personal identity, and social status of each individual. Social obligations and rights or privileges were structured around the family. The oldest members of the family had greater authority over decision-making and other obligations than younger members. Decisions were based on consensus of family councils. Because of the closeness and reliance on each other, it was imperative that families lived in harmony, respected authority and fulfilled their duties and obligations. Family unity was maintained by celebrating feasts or other important occasions, as well as by helping each other in time of need.

Spanish friar Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora who lived among the CHamorus in Rota in 1602 observed and wrote of how loving and caring native families were of each other — in his mind, enough to put Christians to shame. For example, he described how relatives worked together voluntarily and with compassion to help out in times of illness or to accomplish heavy tasks, such as building or repairing houses. People knew that such favors would be returned in kind:

On the day an indio [CHamoru native] is ill and cannot go fishing, his son will appear on the beach at the time the other village fishermen are returning. The latter will know that the father or brother is ailing, and, consequently, they will share some of their catch with him. Although he may have a house full of salted fish, they will give him some of the fresh catch so that he will have it to eat that day. The day when the master of the house, or his wife, or a child falls ill, all the relatives in the village will take dinner and supper to them, which will be prepared from the best food they have in the house … until the patient dies or recovers. When their houses are old, or when they wish to repair or rebuild them, all the relatives and neighbours in the village gather the necessary materials. On the designated day, they will get together to construct it, even though it may be from the ground up, and within half a day, or two or three days, they will complete the house for him…Not only will they build their relative or neighbour’s house, they will also provide meals for him and for his entire household, as well as for themselves. The situation is that, what I do for my relatives and friends, they will also do for me.

Relatives helped with fishing expeditions (such as catching mañahak during their seasonal runs), canoe-building and repair, cultivating fields and gathering food. Children were expected to respect and care for elders, and likewise, older relatives cared for and nurtured children. Fray Pobre was particularly impressed with how children were raised and disciplined with love:

While they are very young, they [men and women] make their sons and daughters work and teach them to perform their tasks. Consequently, the very young know how to perform their tasks like their parents because they have been taught with great love. So great is their love for their children that it would take a long time to describe it and to sing its praises. They never spank them, and they will even scold them with loving words. When a child is offended and angered by what is said to him, he will move a short distance away from his parents and turn his back to them, not wanting to face them. They will then toss sand or pebbles on the ground behind him and, after he has cried for a little while, one of his parents will go to him and, with very tender words, will take him in his arms or raise him to his shoulders and carry him back to where the others are gathered. Then they will always give him some of their best food and, speaking to him as if he were an adult, tell him how he should behave, admonishing him to be good. With such great love, these barbarians raise their children, that they, in turn, grow up to be obedient and expert in their occupations and skills.

In addition to work, CHamoru families participated in numerous feasts. Celebrations with extended families were occasions to relax, eat, dance, sing and compete with each other in feats of strength as well as to demonstrate debating skills. These gatherings also were opportunities for different families to reciprocate prior obligations and to strengthen or renew family bonds. Family bonds often were determined by lineages.

Descent, lineage and clans

Extended families can be quite large, and usually include relatives considered “close,” such as grandparents, parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins, nieces, nephews, and grandchildren. Family members are considered relatives either biologically—in which case they are known as “blood” relatives or consanguineal relatives—or culturally through marriage; such relatives are known as affinal. Other relatives may be adopted into families, too. In CHamoru culture and other Micronesian island cultures, adoption is an important feature of family and is one way new members join.

Most societies recognize two sides in each family—the mother’s side and the father’s side. Each of these sides is called a lineage. The father’s lineage or father’s side of the family is called a patrilineage, while the mother’s side is called a matrilineage. Lineages are important for understanding different forms of kinship among human societies. Lineages tell us how individuals trace their ancestry and how societies determine patterns of inheritance, obligations and privileges.

Lineages are sometimes referred to as genealogies, or lines of descent. This means people of the same lineage can trace their descent from a common apical ancestor — a great, great, great, great, great grandparent, for example. Sometimes the apical ancestor is not remembered by name, while in other cultures, genealogies are continually remembered in special chants and ceremonies.

Some societies recognize both lineages as equally important for determining an individual’s personal identity or blood relatives. This is called bilateral descent, and it is the standard in North America. Societies with bilateral descent value the nuclear family as the main economic and social unit. Although an individual may be “close” to the mother or father’s side through geography or other factors, neither parent’s side is privileged over the other. However, most other societies in the world have unilineal descent, whereby one lineage is privileged over the other in determining inheritance or blood relatives. Patrilineal societies trace inheritance through the father’s side and matrilineal societies privilege the mother’s side. Kinship through unilineal descent can be quite complex.

In patrilineal societies, for example, individuals belong to the line of their fathers. But since societies are comprised of both males and females, women, too, trace their lineage through their father. Often, men and women of the same patrilineage are not allowed to marry each other. Because of this, mothers are usually of a different patrilineage than their husbands or the father of her children. Another complexity is seen when dealing with cousins. An individual will share a patrilineage with a father’s brother (the individual’s uncle) and his children (cousins), and also with their father’s sister (aunt), but not her children, who will share a patrilineage with their father.

Achafnak

Ancient CHamoru society, however, is believed to be matrilineal, so the maternal line was more important for determining who one’s relatives were. The old CHamoru word for matrilineage is achafnak, meaning “of same birth,” or “relatives from the same womb.” In the achafnak system, a male belonged to the same descent group as his mother, his mother’s mother (grandmother), the mother’s siblings (aunts and uncles), and the mother’s sister’s (aunt) children (cousins). In addition, his children belonged to their mother’s descent group.

The mother’s line, therefore, was also the important economic and social unit, controlling land and other resources. Members of a matrilineage had privileged access to their ancestral lands and also the authority to determine who else would be able to use them. Because land was limited, it did not belong to single lineages. Instead, ancestral lands were maintained by clans.

Clans are groups of two or more families or lineages who claim descent from a common ancestor, although they cannot trace the exact genealogical links to that ancestor. Clans form when a lineage continually expands generation after generation. The lineage may grow too large for its resources, and so the lineage may split into smaller lineages which still recognize their original ancestor. A clan differs from a lineage in that the members are more dispersed, meaning they may live apart from other related lineages.

Clans organize families into political and economic groups. They take care of each other’s needs, celebrate important events together, and fulfill obligations and responsibilities. They go to war or seek revenge as a clan. Clans pull all their resources together for the benefit of the group as a whole.

Ancient CHamoru clans managed their own affairs and no single clan or leader extended their authority over other clans and villages. Historians often cite this feature of decentralized authority as an explanation for how the Spanish were able to effectively challenge the CHamoru. Kinship was also reflected in the CHamoru practice of ancestor worship. Deceased ancestors were venerated by signs of respect to their skulls, which were removed after burial and kept in family homes. Requests for success in war, fishing, farming and other aspects of daily life were made to the ancestors in special ceremonies, often through the intervention by a makana, or spiritual herbalist or traditional healer.

Each member must be born into or adopted (poksai, “to nurture”) by the clan. Children who lost both parents would be adopted and cared for by relatives. The clan determines individual roles and responsibilities, who they will marry, and where they will live. There is a system of ranking within clans, and usually older relatives are given leadership roles over younger ones. In a matrilineal society, although descent passes through the female line and females have considerable power, women do not have exclusive authority, and often share power with other male relatives, usually brothers and not husbands. This is because in a matrilineal society, the highest-ranking male in an individual’s family is not the father (who belongs to his mother’s clan), but rather, the mother’s brother, or the individual’s uncle. So, while a husband had less authority in his household than his wife, he could still exercise his authority in the households of his sisters.

We see in ancient CHamoru society, for example, the eldest sons (maga’låhi) and daughters (maga’håga) of a clan had the most authority. The oldest brother allocated property rights, organized labor, settled disputes, and represented the clan in all outside matters. The senior woman of the clan had authority over women’s work and activities, and although her power was limited, decisions affecting the clan were rarely made without consulting her, too. Ranked female relatives were the ones to whom gifts of food or turtle shell were presented in different ceremonies and feasts.

Indeed, the social relationship between brothers and sisters represented a more important, lasting bond than the relationship between husbands and wives. While marriage bonds between husbands and wives affected the ways different clans interacted or affiliated with each other, brother-sister bonds determined land tenure. Click to know…Poksai

Kinship and land tenure

Chamorro Kinship Terminology

American anthropologists Laura Thompson (1941) and Alexander Spoehr (1950) each studied and wrote about CHamoru culture in Guam and Saipan, respectively. Based on Thompson’s work and his own, Spoehr listed CHamoru kinship terms that were still in use in the Marianas. Interestingly, the terms for “sibling” (chelu), “child” (patgon), “son” (lahi) “daughter” (haga) and “spouse” (asagua) are the only CHamoru kinship terms that remain, all others being derived or borrowed from Spanish. The collective term for parents (saina) in CHamoru is also retained. The plural form of saina, manaina, includes parents, siblings of parents (aunts and uncles), grandparents, and also siblings of grandparents, and godparents.

Land tenure

Land tenure is a concept that explains a group’s ideas, rules and practices regarding access, rights and ownership of land, as well as of the resources on that land. Traditionally, land tenure is based on accepted social customs of the group. Since families often use land together, the notions of kinship and land tenure go hand in hand. Among the Pacific Islands, land tenure systems are diverse, but share a few common elements.

Ideally, land tenure systems are meant to help a group organize rights to use certain areas for purposes of subsistence, including foraging, agriculture, fishing or hunting. Land tenure customs are also conditional or negotiable. This is because people do not “own” the land, but rather, people have rights to use land, by way of their relationships with other people. Lineages and extended families determine individual rights, but marriage and adoption into lineages also play a role. Because islands have such limited land area, island societies have to make sure that the land is used efficiently to meet the needs of the overall community. In addition to land, access to water was also determined by customs of kinship and lineages.

In ancient CHamoru society, land rights were controlled solely by high-ranking clans from the upper chamorri caste. The low caste manachang could not own property, and therefore, they had to get permission from the chamorri to cultivate the land. For this privilege, they gave part of what they grew to the chamorri.

Often, related families would reside together on land controlled by a particular lineage. As stated earlier, because CHamoru society was matrilineal, land was passed through the female line. When women married, though, they moved to their husband’s ancestral lands. Sons would move to their mother’s lands until they were ready for marriage. Their mother’s brother would determine which lands his nephews could reside in or cultivate. The customs regarding marriage and residence were adaptive strategies for life in these small island communities.

Marriage customs

All societies have some notion or practice of marriage. Broadly speaking, marriage is a socially approved economic and social union, usually between a man and a woman. In ancient CHamoru society, marriage was exogamous, meaning one had to marry outside of one’s clan, because marriage to a close relative was considered incestuous and taboo.

CHamoru marriages were also monogamous — men and women had only one spouse at a time. Marriage was also limited by one’s social status — one could only marry within their caste. Once a couple married, there were customary rules which determined where the pair would reside. In anthropology, these rules of residence depend on the type of clans found in the society.

Early CHamoru clans likely were organized as matriclans—clans with matrilineal descent. Matriclans usually have a matrilocal residence pattern—daughters stay but sons leave when they marry. In other words, upon marriage, the husband would join his wife’s clan and reside in her clan lands or territory. Additionally, any children they had would belong to their mother’s clan.

Over time, however, it seems that CHamoru society shifted to an avuncuclan system as observed by the early Spanish missionaries. In this system, the clans were still matrilineal, but the wife moved to her husband’s territory and raised her children there. The men in avuncuclans inherited their land rights through their mother’s line. Their children were members of their mother’s clan. Daughters stayed with their families until they married, after which they would live in their husbands’ lands. Grown sons, on the other hand would move to their mother’s clan lands and take up residence near and be supervised by their mother’s brother (their uncle). The young men resided in the guma’ uritao (bachelor’s house) until they were ready to marry. Click to know…Uritao

Although marriage celebrations in ancient CHamoru society could be quite elaborate, marriages were not binding, and were easily dissolved. According to historic descriptions, a man stood to lose a lot if he left his marriage, while women seemed to have had fewer negative consequences. Women who divorced got the children and the man’s possessions. However, whether the couple stayed married or divorced, inheritance of his land went to his sister’s children, ensuring the land remained in control along female lineages. Click to know…Umayute’

Warfare, alliances and kinship

As transient as marriage could be, it was still an important means by which clan alliances were established. Through marriage, individuals could gain access to a clan’s resources with permission. Warfare was another way clan alliances were established or shifted. Ancient CHamoru warfare was different than the Western style of warfare we know today. It was more ritualistic, intended to elevate a clan’s status, resolve quarrels and disagreements, and rectify infringements on territorial or fishing rights, rather than to destroy rival clans. Fighting between clans happened often, but did not last long, and was never large in scale. When a few warriors were killed, peace was almost immediately negotiated. Warfare also occurred when clans split apart and formed new settlements or villages.

Alliances that formed between clans were important because allied clans helped defend each other during times of war. Clans that were friendly to each other could provide marriage partners, as well as engage in trade for desired products or resources, or participate in reciprocal gift giving (chenchule’). Clan alliances could also allow clans access to land or fishing grounds. However, clans that failed to fulfill obligations to each other could be punished or not receive help when they needed it. The shame and embarrassment of being unable to carry out a clan’s obligations was ultimately worse than being denied assistance.

Archeology of land tenure and kinship

Kinship and land tenure are anthropological concepts that are not always easy to demonstrate from archeological data. However, evidence of settlement patterns and the presence of artifacts that indicate residential use of specific areas may reveal aspects of social interaction between groups of people, such as kin groups and non-kin groups. We also may learn more about their subsistence activities, and the relationship of kinship to rules of land tenure.

Unfortunately, very little is known about the early occupation of the Mariana Islands in the early Pre-Latte Era (about 3,500 years ago), although some archeologists suggest that the coastal regions of the larger southern islands were probably settled first. Additionally, the presence of similar kinds of redware pottery on Guam, Rota, Tinian and Saipan indicate the people on these islands were relatively mobile and had frequent contact with each other. Over time, as populations grew, people moved into the interior of the islands, expanding their use of marine and coastal resources to include the gathering and cultivation of resources from inland valleys and grasslands. Because of the tropical climate and seasonal typhoons and droughts, the ancient inhabitants likely were quite flexible in their land usage, frequently moving but maintaining long-term access to certain areas that were more consistently productive. These areas would be accessed cooperatively through kin ties. Other areas, such as the smaller islands to the north could have been used for procuring more specialized resources, like birds, crabs, fish or raw materials for tools.

By the Latte Era (about 900 AD), the inhabitants of the Marianas occupied more permanent village sites. The increased population density over the years had brought other social and cultural changes, including the need for regulating access to arable or farmable land, fishing grounds and food collection areas. Thus, the system of clans and lineages to control lands had developed, which ensured adequate food production in spite of an increased number of people exploiting the available resources. Increased competition for these resources stressed the importance of alliances between clans. Other features of culture, including practices of warfare, marriages, clan alliances, feasts and gift-giving, subsequently became means of negotiating land usage and inheritance.

Archeologists observed that as CHamoru populations became more settled and less mobile, their technology and activities also shifted. They used raw materials differently in the production of new kinds of tools for fishing, farming and warfare. Likewise, they needed to produce and store greater amounts of food for larger populations, which impacted the manufacture of pottery and the construction of homes and storage facilities. Pottery became larger and stronger and shaped more for cooking and rehydration of dried foods; with regard to storage facilities, rules would have to be set in place to determine access to stored foods. The clan leaders would have been responsible for outlining and enforcing these rules.

By examining accumulated artifacts, archeologists have been able to suggest the use of certain spaces as either residences or sites for more communal activities and rituals. This is because people tend to leave behind refuse and the remains of the things they ate or used, which accumulate the longer a place is occupied. Some of the Spanish accounts describe the presence of structures for residences, canoes, and general public use. Canoe houses were associated with small cooking houses and other dwellings along the shore. However, in studying sites in the Marianas, it is not clear how activities were delineated within the household structure—in other words, which areas were specifically used for cooking, sleeping, eating or for entertaining guests, as the earliest Spanish accounts do not describe these in detail.

Latte sets have also received considerable interest from archeologists. Latte stones, the distinctive stone structures that appear only in the Marianas, may have served as the foundations or supporting posts for specialized houses such as canoe houses, men’s houses (guma’uritao), or residences for high-ranking individuals. Coastal sites where latte villages have been found contain numerous artifacts to suggest relatively intense occupation for many years. Inland latte sites, however, have fewer associated artifacts, which may mean these sites were occupied late in CHamoru history, or not at all. Some archeologists suggest that these sites, instead, may have been used to mark territories as belonging to particular clans or lineages.

Clans and lineages also could claim territories through burials. Burials at latte sites seem to demonstrate this. Burials within the household were the practice described by Spanish missionaries, especially for individuals of high social status and strong matrilineage. Cave burials and cremations, especially those found in locations in Saipan, are more puzzling, and seem to be associated with lower ranked individuals, but this is not fully substantiated. Historic accounts have described that villages of lower ranking clans were located in the interior or less desirable coastal areas, and one suggestion is that, because of their location, cave burials or cremations may be the kind of mortuary practice for persons of low social status. More study, however, will need to be done to resolve this issue. Click to know…Latte

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.

Ember, Carol R., Melvin R. Ember, and Peter N. Peregrine. Anthropology. 12th Edition. Upper Saddle River: Pearson College Div, 2006.

I Ma Gobetna-na Guam: Governing Guam Before and After the Wars. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1994.

Kottak, Conrad P. Mirror for Humanity: A Concise Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 4th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2005.

Petersen, Glenn. Traditional Micronesian Societies: Adaptation, Integration, and Political Organization. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.

Russell, Scott. Tiempon I Manmofo’na: Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1998.