Burial practices and culture

One of the distinguishing features of our humanity is the way in which people treat and understand death. Death is not only the end of a living organism’s biological functions, but entails a variety of cultural responses and ritual activities that go beyond recognizing the end of an individual’s life. These responses and rituals reflect a particular society’s cultural beliefs, values and understandings about death and dying. As a cultural universal, the ways in which people prepare for death, engage in rituals of mourning, manage the deceased individual’s physical remains, and express the spiritual beliefs or notions of what happens after death are all part of the complex of activities and meanings that are associated with the final phase of human life.

Studying rituals and practices surrounding death can reveal much about a social group’s culture, history and spiritual beliefs. For example, today on Guam, many of the rituals and beliefs about death and the afterlife are rooted in the traditions of the Roman Catholic Church, which the Spanish established among the CHamoru people beginning in 1668. However, considering the Mariana Islands had been occupied for thousands of years, the ancient inhabitants surely had rituals and beliefs concerning death that preceded the influence of Christianity.

Archeological records and early Spanish missionary accounts provide information about the practices of the ancient islanders. Although the meanings and customs surrounding death may have changed for the CHamoru people, the deep respect for the dead and the communal response to grieve, console and commemorate a loved one remain. Interestingly, the practices that many CHamorus are familiar with today—wakes (bela), rosaries (lisayo), funeral Masses, burials, ika’ (monetary gifts) and even the food prepared for these occasions, demonstrate the mix of Christian and CHamoru traditions that resulted from many years of Spanish colonization.

Questions remain, however, as to how the CHamoru people treated their dead before Christianity became infused with their beliefs, and what kinds of changes in burial practices occurred over time.

Prehistoric burial practices on Guam

In every human society the treatment of the dead reflects in some way the social, political, and spiritual character of that society. The study of prehistoric burial practices offers unique insights into aspects of prehistoric life that often cannot be recognized by any other means. This is particularly relevant in regard to the ancient CHamorus, who left very few clues as to the nature of their ancient society and their belief systems.

Archeologists on Guam have examined hundreds of prehistoric burials at Latte Period sites (AD 1000 to AD 1521) and, to a lesser extent, the earlier Pre-Latte period sites (500 BC to AD 1000). By analyzing these burials, much has been learned about the ways of life of the ancient people, including their burial, or mortuary practices.

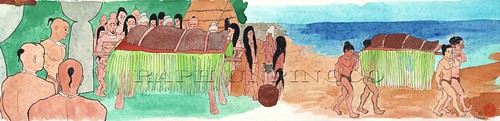

Funeral rituals

We know little of the rituals that accompanied the burial of the dead because evidence of rituals rarely survives in the archeological record. However, an account of a funeral and burial in the early 17th century by Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora, a Spanish friar who lived among the CHamorus in Rota, indicates that interment or burial of the deceased involved elaborate rituals and customs.

Latte period burials

Ancient burials can be found throughout Guam and the Northern Marianas, although the majority of burials have been encountered along the coastline, where permanent densely occupied prehistoric villages once existed. Latte Period burials are often found in groups that cluster in the vicinity of latte structures―large monoliths of coral or stone arranged in parallel pairs―which may indicate that the clustered individuals were related by clan. Because many people were eventually buried in the same areas over a long period of time, new graves sometimes intruded upon earlier burials, which resulted in mixing (or “commingling”) and scattering of skeletal remains.

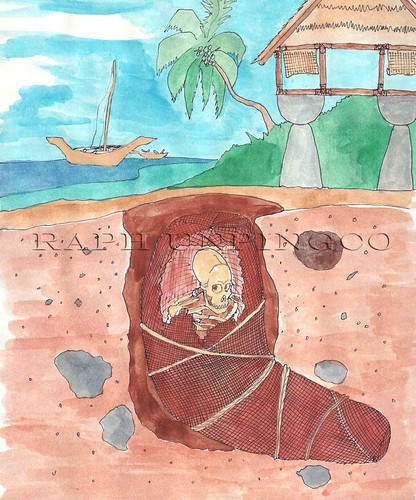

Latte Period people were typically buried in a supine position (on the back) or leaning to the side. Their legs could be extended, flexed, or semi-flexed. Some are so tightly flexed that they appear to have been wrapped for burial. They are often found with their heads directed inland, their feet towards the coast.

Some studies have suggested that children and adults were buried in separate areas. There is no concrete indication, however, that men and women were buried in separate areas. Unlike pre-Latte burials, Latte Period people did not typically bury their dead with grave goods or funerary objects, although there have been occasions where slingstones, a fishhook, or other items were buried with the body.

Feet Towards the Sea

It has been suggested that this practice may have important symbolic meaning, although what the exact belief is has not been made clear in either archeological studies or missionary accounts.

In modern-day Guam, this practice – burying the dead with feet towards the coast – has continued with several cemeteries set up this way.

Bone collection

The retrieval of bones from a deceased body after the soft tissue has deteriorated is evident in many Latte Period burials. The skull or long bones (most commonly the tibia or shin bone) were extracted from the earth after individuals had been buried for a period of time. The long bones were often crafted into speartips, fishhooks or other tools, but it is not known how the skulls were used. Professor Marjorie G. Driver of the University of Guam Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center who translated several Guam-related Spanish historic documents, relates a historical account of the skulls being used for ancestor veneration and for both good and bad luck. Often, skeletal elements were reburied, resulting in what is known as a “secondary burial.”

Pre-Latte burials

Naton Beach Burials

Pre-Latte burials were rarely seen on Guam until excavations in 2007 at Naton Beach in Tumon revealed more than 200 individuals dating from the Pre-Latte period. The Naton burials represent the largest and best preserved early mortuary population yet identified in Micronesia. In comparison with more recent prehistoric burial populations, the early Naton Beach skeletons exhibit significant differences in the use and placement of artifacts and treatment of the human remains.

For example, the Naton Pre-Latte people consistently buried their dead in a fully extended, supine position, with the arms at their side which is in sharp contrast to the Latte Period pattern that shows much more variability. What the Pre-Latte at Naton and Latte people have in common is the tendency to point the feet towards the sea.

At Naton, numerous grave goods were associated with the Pre-Latte interments, including ceramic vessels, shell bead necklaces, shell bracelets, stone adzes, shell adzes, stone pestles, shell fish gorges, stone net sinkers, large unmodified oyster shells, a shell fishhook, and a shell net sinker.

Fiesta Resort Burials

Several burials examined at the Fiesta Resort Guam (formerly the Dai Ichi Hotel) site in Tumon were associated with radiocarbon dates and pottery from the 1st Millennium AD, although the burial practices there were different from those noted at Naton Beach. Four individuals had been buried in a seated or reclining position, with legs crossed. Burial had Latte and Pre-Latte pottery sherds nearby, which made the age of the burial unclear. This particular burial consisted of the partial, articulated remains of an adult male who had been buried in a seated position facing east, with legs tightly flexed, feet adjacent to one another and the knees spread wide. Extra bones―a skull, two mandibles, three arm bones (two radii and one humerus) and two upper leg bones (femurs) representing four other people had been stacked between his knees. The intrusive bones appeared to have been placed there at the time of his burial and were probably already skeletonized.

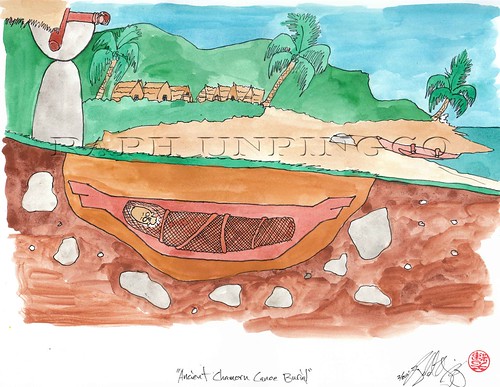

Canoe burials

At Latte Period sites on the west coast of Guam, nine human skeletons were discovered within canoes that had been used as coffins. Although only very small fragments of the actual wood from the canoes remained, archeologists were able to define the shapes of these canoes in the soil surrounding the human skeletal remains. In several instances, canoe burials were defined by concreted beach sand clearly in the shape of a canoe. The unintentional development of the concreted matrix may have occurred over time, as occasional soaking of the buried boat resulted in the dissolution of the organic material (from the corpse) while at the same time concentrating and containing limestone and sand that eventually became cemented around the skeleton.

There is little variability in the dimensions of the canoe containing the burials. Lengths of the mortuary “vessels” averaged 2.32 meters (7 feet 7 inches). Shapes were varied; ends were rounded, triangular, rectilinear or square, and were semicircular in cross-section. Maximum breadth averaged 0.4 meters (1 foot 3 inches), while height and thickness of the canoes average 0.3 meters (9 inches).

The recovery of small fragments of breadfruit from one of the canoes suggests that breadfruit trees were used for canoe construction, in at least this instance. Analysis of microscopic plant remains recovered from these burials has revealed a high concentration of pandanus, suggesting matting or wrapping material was used for the bodies.

The canoe burials on Guam were recovered from Latte Period villages with burial clusters and habitation (housing) structures close by. No young children have been found in canoe burials, but otherwise, there does not appear to be a relationship to age or to sex. Of the nine canoe burials known thus far, six are females and three are males. Three of the females were in their late teens, and three were between 30 and 45 years old. Two of the males were in their mid-teens; one was 35-40 years old. The social significance of the comparatively rare mortuary treatment of the canoe burial is not known.

For further reading

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation. Tiempon I Manmofo’na. Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. By Scott Russell. Micronesian Archaeological Survey No. 32. Saipan: CNMIHPO, 1998.

Coomans, Peter. History of the Mission in the Mariana Islands: 1667-1673. Translated by Rodrigue Lévesque. Occasional Papers Series, no. 4. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2000.

DeFant, David G., and Joanne Eakin. “Preliminary Findings from the Naton Beach Site, Guam.” Paper presented at the Pacific Island Archaeology in the 21st Century Conference, Koror, Republic of Palau, July 2009.

DeFant, David G., Joanne Eakin, and Lynn R. Leon Guerrero. Archaeological Monitoring and Data Recovery, Fiesta Resort Guam Improvement Project. Maite: Paul H. Rosendahl, PhD, Inc., 2008.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.

García, Francisco. The Life and Martyrdom of Diego Luis de San Vitores, S.J. Translated by Margaret M. Higgins, Felicia Plaza, and Juan M.H. Ledesma. Edited by James A. McDonough. MARC Monograph Series 3. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 2004.

Graves, Michael W. “Organization and Differentiation within Late Prehistoric Ranked Social Units, Mariana Islands, Western Pacific.” Journal of Field Archeology 13, no. 2 (1986): 139-154.

Paul H. Rosendahl, PhD, Inc. Tumon Bay Hyatt Hotel Archaeological Data Recovery, Tumon, Tamuning Municipality, Territory of Guam. By E. Melanie Ryan, Bradley J. Dilli, and Alan E. Haun. Report No. 797-090999. Hilo: PHRI, 1999.