Agad’na: Canoe Builders

Impressive craftsmanship

The ancient CHamorus who were skilled at canoe building and navigation were called agad’na. Early European accounts regularly marveled at these CHamoru vessels, William Dampier, saying in 1681 for instance that:

One cannot stop talking about their great velocity, craftsmanship and lightness, because in the whole universe I do not believe there is a thing equal to them in nimbleness and swiftness.

Another visitor, Woodes Rogers in 1711, said:

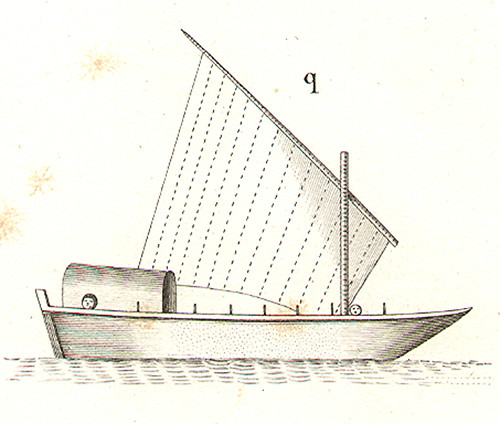

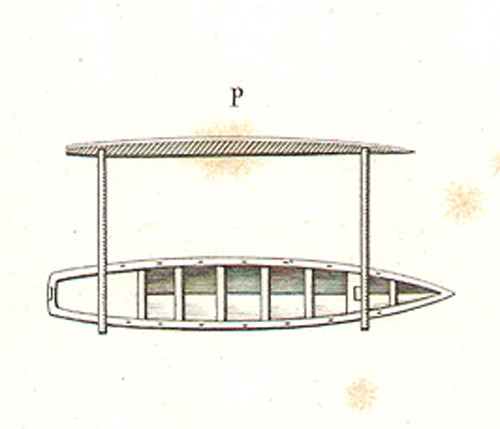

The Governor presented us with one of their flying prows, which I shall describe here because of the oddness of it. The Spaniards told me it would run twenty leagues per hour, which I think too large; but by what I saw they may run twenty miles or more in the time, for when they viewed our ships, they passed by us like a bird flying. These prows are about thirty foot long, not above two broad, and about three deep. They have but one mast which stands in the middle, with a mat sail, made in the form of a ship’s paddle to steer her, so that when they go about, they don’t turn the boat as we do to bring the wind on the other side, but only change the sail, so that the Jack and sheet of the sail are used alike. The boat’s head and stern are the same, only they change them, as occasion requires, to sail either way. For they are so narrow that they could not bear any sail, were it not for booms that run out from the windward side, fastened to a large log shaped like a boat, and nearly half as long, which becomes contiguous to the boat. On these booms a stage is made above the water on a level with the side of the boat, upon which they carry goods or passengers.

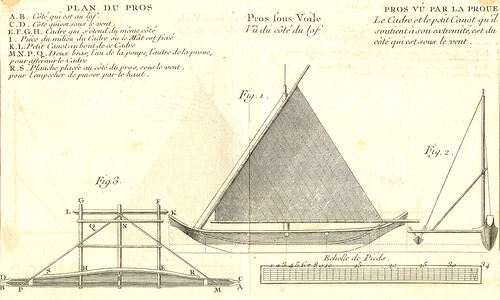

They were called “flying proas” because of their speed, and possessed three technological innovations which made this label well deserved:

- Their hull was asymmetrical to counter the drag of the outrigger float.

- CHamorus used triangular sails to increase speed and allow for a closer sail to the wind.

- The proas tacked by moving the sail from one end of the canoe to the other. This is called shunting and is done because the outrigger float must always be to windward.

So fast were these vessels that one voyage from Guam to Manila reportedly took only four days, which means they traveled more than twenty miles per hour.

These canoes were vital to the survival of CHamorus because they facilitated transport and trade among islands and allowed them to fish beyond the reef.

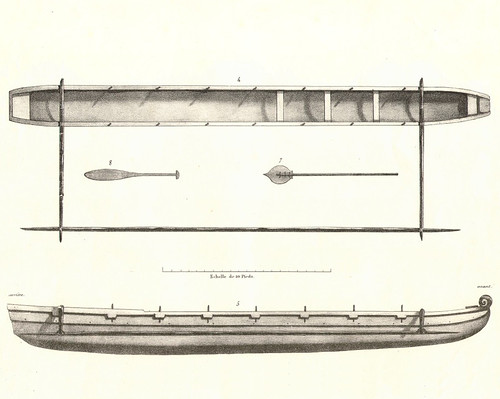

Ancient CHamorus had at least six types of canoes: sakman, leklek, duding, duduli, panga and galaide. The sakman was the largest and most impressive, regularly measuring more than 40 feet, some reportedly holding a 100 men, ideal for long voyages, and deep sea fishing. Leklek, duding, and duduli were smaller vessels for shorter voyages. The panga is a duduli without a sail. The galaide, also without a sail, is a small vessel. Both the panga and galaide were used within the reef.

Canoe construction and navigation were considered men’s tasks, and most likely specialized to a select few. The learning of these skills were either passed down from father to son, or a part of a young man’s education in the guma’ uritao or men’s house.

After a suitable tree was cut down, usually dokdok or breadfruit, a skilled carver would begin to shape the canoe using a higam or shell adze as well as fire. If the canoe was to be longer than eighteen feet, more than one tree trunk would be needed and one of the most difficult tasks was making sure that different sections of the hull would fit securely. These sections were lashed together and then sealed using plant fibers and tree sap.

In addition, pieces such as the palu or mast, the outrigger, and the umulin or rudder would have to be carved and attached. The hulls would be colored in white, black, red or orange by using red dirt, afok or lime, coconut oil and soot, which both beautified them and offered protection from bad weather. Women were responsible for the construction of the layak or sail. They would weave together small sections of akgak or pandanus mats, to form a huge triangle which would then be attached to the palu.

Ancient CHamorus, like other Micronesian islanders, used an impressive array of skills to navigate their magnificent vessels. Most important was the use of the rising and setting of stars to plot their course, but also vital were the abilities to discern differences in wave patterns, sea life, ocean color, and cloud formations.

By Michael Lujan Bevacqua, PhD

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Diaz, Vicente M., director. Sacred Vessels: Navigating Tradition and Identity in Micronesia. Moving Islands Production, 1997.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

I Manfåyi: Who’s Who in Chamorro History. Vol. 1. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education and Coordinating Commission, 1995.

Russell, Scott. Tiempon I Manmofo’na: Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1998.