Editor’s note: The following was adapted from The Pattera of Guam: Their Story and Legacy written by Karen A. Fury Cruz which was made possible, in part, from the Guam Humanities Council in cooperation with the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Interviews – 1995

The stories of Guam’s pattera, or nurse-midwives, and their history give insight into their personal legacy and professional contribution to the healthcare of women, children, and families in Guam.

Their stories presented here are derived from the personal interview conducted with three pattera in 1995 who were trained by the US Navy, licensed as midwives, and who were self-employed for all or part of their careers. These nurse-midwives were identified by contacting their relatives, several village mayors, and nurses, and by reviewing birth registration records and a legislative resolution by I Mina’ Disisais na Liheslaturan Guåhan/the Sixteenth Guam Legislature.

By Karen A. Fury Cruz, RN, MPH

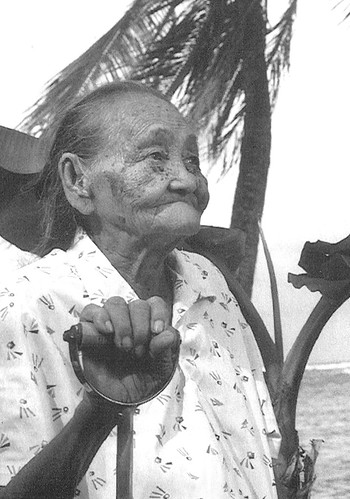

Tan Ana Rios Zamora

Estorian Tan Ana Rios Zamora (Interview conducted in November 1995)

| Full Name | Ana Salas Rios Zamora |

|---|---|

| Better Known As | Ana Rios |

| Date of Birth | 22 April 1905 |

| Parents | Father: Felipe de la Rosa; Mother: Antonia Megofna Salas Rios |

| Siblings | Second of seven children; two brothers (one deceased) and four sisters (two deceased) |

| Husband | Dorotheo Zamora (deceased); married in 1946 |

| Children | Juan, June 1920 (deceased); Agueda, October 1925 (deceased); William, October 1931; Jesus, May 1933; Jose, May 1935; Antonio, May 1938 |

| Education | Second grade; nurse-midwife training |

| Residence | Piti |

The Interview

“I am the oldest midwife,” says Tan Ana. She received her nursing and midwife training at the U.S. Naval Hospital in Guam well before World War II. The exact years are lost to memory, but are estimated to have been in the 1920s. One of her aunts took her to work at the hospital in Hagåtña. “Ward 2,” says Tan Ana.

Tan Ana says she delivered “many babies. My work is all right; everything is all right. Thank God that I don’t have any mistake. I appreciate what God [does],” she says.

According to her son Jose, who assisted during the interview, Tan Ana kept a record book of all the deliveries she attended; however, the book was destroyed during a typhoon. Jose recalls that his mother went all over the island to deliver babies and was sometimes gone for three days at a time. He says, “The husband [of the pregnant woman] came to pick her up. The husband will give my Mom-lucky if she gets twenty dollars-but mostly ten dollars for the delivery. She put that in income tax; that’s how she got Social Security.”

She worked during the Japanese occupation as a midwife and continued for over twenty years after the war, according to Jose. “A lot of people know her,” says Jose. “She’s very patient, you know. People at that time [had] very little money to go to the hospital, so mostly they grab her to deliver [the babies]. Sometimes she delivered over here at the house; they came over here to deliver at the house.”

Having an extended family available to provide childcare when she needed it made it possible for Tan Ana to have her own family and also be a midwife. Jose recalled, “My auntie used to stay here; she’s single, so she [watched] us while my Mom is gone. Also a goddaughter and my grandmother, we were living together. My grandmother [Tan Ana’s mother] understands that [my mother] has to go [to deliver babies] because she has lots of kids and she has to feed us.”

Tan Ana used traditional Chamorro herbal medicine and massage in her practice and, in addition to the pregnant women, she also saw children who were ill. Compensation was minimal. “Sometimes one dollar, the most five dollars,” says Jose. “During that time, the people have very little money. So, what can they afford? Sometimes they just take from the ranch, you know, food, vegetables, and all that, and give it to her. No money at all.”

Legislative recognition was given to Guam midwives in 1982, recalls her son. Tan Ana was among those recognized.

Comments

In an interview conducted in 1975, Tan Ana reported that her nurse-midwife training lasted for two years and that the nurse-midwife “techniques were no different from the doctors, except that [midwives] were not allowed to administer anesthesia” Tan Ana started nursing school in 1922 and practiced until 1928, when all midwives were called upon to work in the hospital because of outbreaks of dysentery and typhoid fever. In 1933 she went back to practicing midwifery and continued to do so until 1967. In that year, one birth was registered with her name as attending midwife. Tan Ana was unique in that in her practice she combined traditional Chamorro herbal medicines with her formal training as a nurse-midwife.

Tan Ana died on May 16, 1996, at the age of 91, two months after her son Jose had died. The funeral announcement in the Pacific Daily News simply, but memorably, referred to her as “midwife and suruhåna” (traditional doctor) (May 24, 1996). At her funeral, the governor of Guam presented a posthumous award to Tan Ana in recognition of her services.

Tan Joaquina B. Herrera

Estorian Tan Joaquina B. Herrera (Interview conducted in November 1995)

| Full Name | Joaquina Babauta Herrera |

|---|---|

| Better Known As | Tan Kina’ |

| Date of Birth | 9 February 1914 |

| Parents | Father: Jose Patricio Babauta; Mother: Teodora San Nicolas Babauta |

| Siblings | Youngest of five children; three brothers and one sister (all deceased) |

| Husband | Jesus Santos Herrera (deceased); married in 1944 |

| Children | Rose, August 1945 (died 1992); Joseph, March 1948; Frankie, June 1949; Gloria, May 1951; David, June 1955; Eleanor, February 1960 |

| Education | Fourth grade; nurse-midwife training |

| Residence | Hågat/Agat |

The Interview

In 1938, a Navy wife encouraged Tan Kina’ to apply for nurses training. At that time, war was expected and Navy dependents were leaving Guam. Her training started in August of that same year. Classes were held Monday through Friday at 1 p.m. for one hour. Tan Kina’ says, “I was so interested to learn and so poor a lady, but I was interested to learn the job.” The training was held in the Hagåtña hospital, and so she had to move to Hagåtña. After class, she went back to the hospital to work until 4 p.m.

The first thing she learned was to clean the bathroom and change the bed linens, bring food from the galley to the patients, take patients’ temperatures, and give patients a bed bath and brush their teeth. Every week the schedule was changed. After six months in training, she was assigned night duty and helped the nurse-in-charge.

Tan Kina’ training lasted almost three years, ending when World War II began at the end of 1941. A certificate was given to those who completed the training.

Just before the war started, Tan Kina’ was on leave and on her way to see her mother in Hågat to give her mother her paycheck. The bus driver asked Tan Kina’ if she had heard anything about war, which she had not. Tan Kina’ recalls: “So when I reach Sumai village [near the big store called Torres store], one of the guys that was on duty that night at the cable [station] called me and said to me, ‘Joaquina, come. Why did you come so early?’ ”

“I said, ‘I got my schedule for p.m. duty, so that’s why I came early to go to the village of Agat to visit my mother and give her my pay.’ ”

“And then he said, ‘Listen. Don’t tell anybody about this, because I’ve been on duty last night and I knew that they’re going to start the war. But they don’t announce it yet here in Guam, but they already, the Japanese, already bombed Pearl Harbor. But don’t say anything, only you, because the guy that was telling me was my patient.’ So he said to me, ‘Instead of going back to the hospital, you better stay home because I think there’s going to be a war.’”

“So I take those words and when I reach home, I told my mother that I am on p.m. duty, but I am not leaving to Hagåtña today. It might be next week when I go back.”

“That hour when I was talking to my Mother, [it] was, I think, about 8:30 in the morning. And then about 9 o’clock, I could hear the plane. My God, that was Japanese already! So then the commissioner of Agat, [began] announcing in the village that ‘You people have to prepare yourself because [we] are going to have war, it’s going to be a war. So if you people can pack your things and stay away in the bushes.’ ”

“So my mother said, ‘What’s the commissioner saying?’ ”

“I said, ‘Mom, don’t worry because I think we’re going to have war.’ ”

“[She] said, “Oh yeah! Don’t worry, but they’re not going to look for us. They’re looking for Americans. So we’re not going to leave our house, Joaquina, we just stay here. And if God does anything about us, we are going to be satisfied of what happened because that is from God.’ That’s what she said.”

“I believe in my mother, so I didn’t even go back to the hospital. My God, during that time, there’s some people having labor pains to deliver, and the midwife in the village wasn’t home. They all left; some of the people left to the boondocks. So I don’t know how come they come to look for me. I said, ‘Oh, my God! I cannot do it because I don’t have [a] license.’ So I said to them, ‘Why not go to the hospital?’ ”

“And they said, ‘No, we cannot because we’re scared.’ ”

“So I was thinking, ‘What am I going to do with the patient?’ I like to be a nurse to help the patient, but even though not in the hospital, even though outside, I like to help.”

“So you know what I did? I went to look for that lady that’s going to have the baby. She’s in labor already, labor pain.”

“So I pray to God, ‘God, please, help me so I can help this lady and the baby.’ ”

“So you know what I did? I got my scissors, and my bandage, and the gauze. That’s all! And I delivered the baby with my hands because I don’t have any protection, either gloves or mask or whatever. So I did it. So that baby is in the States now, the one that I delivered. She married [a man in the] Air Force and they’re living now in Texas. And she [has], I think, four children.”

“Ai! I give God thanks for that. That I [delivered the baby] the right way. But I was not graduated [at] that time yet. I don’t have a license, not graduated, but I did the [delivery] the way it supposed to be to help patients.”

“So then later on when the Japanese already came, they took all the people in the villages and chased [them] out [of] their houses. I think the people were so scared of Japanese too, but I, myself, I wasn’t scared of Japanese. I like those people. So, I don’t know. In the way what I [was] feeling those days, I say now I am praying to God to help me out.”

“In about one year, that is in [1942], someone came to me, this is an old man, and he said to my mother, ‘Where is your daughter?’ ”

“She said, ‘She’s not here.’ ”

“He said, ‘You know, the chief nurse in the hospital told me to tell your daughter to go back to the hospital because they found her name and the captain in the hospital thought your daughter is spying [for] the Americans.’ ”

“So my mother said, ‘Are you going to the hospital?’ ”

“I said, ‘Yes, I think I better go and we do what is good for us. Because if we don’t do it, they are going to kill us because they [are] thinking that I am spying for the Americans.’ But I am not. I am just staying for my mother and, in case we are going to die in the war, I am satisfied that I am with my mother. So, I went back.” During the occupation, the Japanese were in charge of the Hagåtña hospital. Chamorros, as well as the Japanese, were taken care of at the hospital.

“One time after we finished having our dinner in the galley, the chief nurse told us, ‘Listen. The captain told me that we are going to leave this place until it’s time for us to come back again because, “They sure are going to win that war,” the captain says.’ ”

“So, you know what we did-that is at 5:30 after we ate our dinner in the galley? We packed our things, but I don’t take all my things, just half of it. And there’s a patient from Piti and her grandchild, who’s taking care of her, and the other one is a nurse, the same as myself, and they’re living in Piti.”

“So they ask me, ‘Where are you going Joaquina?’ ”

“I said, ‘I don’t know, adai. I think I have to go to Agat.’ ”

“And then my [nurse friend] said, ‘Well, if you want to go to Agat, let’s go together because my auntie is leaving tonight too.’ ”

“So we went together. There are four of us. And we’re just using our [nurse] uniform so that in case the army of the Japanese find us on the way, they are not going to do anything [to] us because the nurse said to us, ‘Make sure and tell the army that you are a nurse so that they won’t do anything.’ ”

“So, the first thing we reach, in Adelup, there’s bunches of army there. And they saw us out [on] the road; it’s almost dark. Then one of the army [soldiers came] up with his [gun] and he asked us, speaking English even though not very clear, ‘Where are you people going?’ ”

“I said, ‘We’re going home.’ ”

“ ‘Who are you?’ he said.”

“We tell him that we are nurses.” (Tan Kina’ repeats this in Japanese.) “That’s what we say to him.”

“He believed us, so he said, ‘Okay, go ahead.’ ” (Tan Kina’ repeats this in Japanese.)

“So we keep going. On that night we reach Piti, I think about 9 o’clock because we are just walking. So, when we reach Piti, the people in Piti are not in the village. They moved [to] the back side of Piti, they call it Malå’a. So we go right straight into that place and we reach [it at] almost 9:30 [or] 10 o’clock. Ai adai!”

“Then we slept that night, and then early in the morning I [said to] the old lady, ‘Thank you very much for making me stay and sleep with you, and I think I have to go and see my mother.’ ”

“The old lady said, ‘Oh, my God, how come you are going to your village? How about when the Japanese and American airplanes come?’ ”

“I said, ‘It’s okay. I’m depending on God.’ ”

“So I keep on, keep on going. When I hear the planes coming, [I am by] a big mango tree and it [has] plenty bushes on the bottom. So I put my things in front of me, and I sat down and waited almost two hours there [until] after their fighting. [When] they left, I started going on again, just by myself. But all what I was thinking at that time, adai, ‘It’s okay no matter what [is] going to happen to me as long as I see my mother again.’ ”

“So then after I reach home, I think [it was] almost 2 o’clock in the afternoon because I walk from Malå’a to Agat. But I’m so slow because I’m tired walking from Hagåtña to Piti to Malå’a.”

“So in the morning, I left to reach Agat. When I was on the road near [the big store at the end of the village of Agat], I was in the middle of the road, [I saw] my nieces and nephews on the road playing [with] each other there. And then they saw me on the road; it’s kind of far. But when they saw me, they knew I am their auntie so they keep on. They keep on going and they met me. And when we met each other, I hugged them and kissed them and I said, ‘How is grandma?’ ”

“They said, ‘Grandma is dead.’ ”

“I said, ‘What!?’ ”

“Grandma is dead and she’s already buried.”

“Oh, my feeling that day. I was so disgusted. The reason why I’m doing all those sacrifices [is] to see my mother and now she’s dead and she’s buried. But I prayed to God, ‘Please help me.’ So we keep going, going, and going until we reach our house.”

“And then my sister-in-law said to me, ‘Ai adai Kumaire, our mother’s dead and she’s already buried. But we are so sorry we cannot let you know about it because nobody could go and let you know about our problems because we don’t have a car. We don’t have anything at all, so we just buried our mother.’ ”

“So I said, ‘Okay, I’m satisfied because my mother is in peace.’ So that time, oh, my God, I said to myself, ‘What I’m going to do now?’ What I told me mother [was] that I would not get married until [she] dies because I want to serve [her] and I want to take care of [her] and now she’s dead. ‘What I’m going to do now?’ ”

“So later on [at] that time, some of people in the village aren’t staying because they were scared so much of the Japanese. So during that time when I reach my home, the captain of the army told us that we have to pack our things and go to Fena. After Fena, we went all the way to Manenggon. So that’s the place where my husband met me and he proposed [to] me.”

“So I told him, ‘I’m not planning to think about anything now. If you really care for me, we have to wait until the war is over because I think the war is going to be over pretty soon.’ ” (This conversation occurred in June 1944.)

“When the Americans came and they found us at Manenggon, they took all the people back to their own place again. So they took us back to Agat, and we stayed in the village of Agat, where the village is now. Before there was no village there, before [only] boondocks. But they built up a camp there, so we stayed there.”

“Then Mr. Herrera said to me, ‘Now that we are in American times, will you marry me?’ ”

“I said, ‘Okay. Okay.’ ”

“‘It’s not much of a problem, you know,’ he told Father Follard, [about] wanting to ask for permission to marry, because he [had] already talked to the commissioner of Agat and the officers, like Commander Minama and Lieutenant Sheperd, and asked for a marriage license. When he had the license already, he let me know, because I was still working in the hospital. We [had] a hospital in Agat where the village is. I think [Guam] had four or five hospitals [built by the Navy]. It’s a tent, but it was a hospital. They [had a] dispensary and wards for the patients.”

“So when Mr. Herrera asked me to marry him, I said, ‘Okay, we can now tell my brother and sister so that they would know that we are going to get married.’ So we did. We got married on September 17, 1944, in a little chapel, just about [the size of this room, where Father Follard said Mass]. So I was still thinking about my mom. I always cry about what happened to me.”

“So then later on, in about three months I think, after we are on the hill with a little tent, they make a little, small house near the beach where the fire station is now. They build a small house of coconut leaves and bamboo. And they make a house for each family.”

“So when the family moved down to the beach, someone [was] having labor pain again. I was working at the dispensary at that time. And then Commander Minama and the corpsman-his name’s December-so Commander Minama said to me, ‘Joaquina, I am leaving tonight and there’s a patient that’s going to have the baby, I think in the middle of the night tonight. Will you stand [duty] for that?’ ”

“I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ ”

“ ‘And December [is] going with you to help you out,’ he said. And, so [I went] with December to listen to that patient who’s going to have the baby and we help each other. She had that delivery about 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning. We fixed the lady and the baby, and then December went back to the dispensary where he was living beside the dispensary, and then I went to my house. In the morning, I went to the dispensary to start working.”

“When Commander Minama came, he said to me, ‘Did you help out the woman?’ ”

“I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ ”

“ ‘And what did she have?’ ”

“I said, ‘She had a baby boy.’ ”

“And he said, ‘Is it all normal, everything is normal?’ ”

“I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ I delivered that woman without [a midwife] license, but Commander Minama allowed me to do it.”

“So when he went back to look for the patient and the baby, and he went back to the dispensary and said, ‘Okay, from now on-I saw [the] child-you have to go and get your license.’ ”

“So I went to Hagåtña. They took me in the jeep. December took me to Hagåtña, and I got my license [from] Commander Stone.” (This was in 1945). “So during that time, oh, my God, I had lots of work to do, working in the dispensary, delivering babies [in Agat] because we are not transferred yet to Adelup. But they are starting the building for a hospital in Adelup.”

“So when the hospital is already built up in Adelup, Commander Minama said to me, ‘I think we are going to be transferred to Hagåtña, Joaquina.’ I said, ‘Hey, Commander Minama, wait and I’ll tell my husband. I’ll notify him if he wants me to go.’ ”

“So when I talked to my husband, he said to me, ‘Oh, my God, are you going to leave us?’ ”

“I said, ‘No. Commander Minama said they are going to offer us a tent for us to stay.’ ”

“But my husband said, ‘Please ask Commander Minama and don’t go.’ Mr. Herrera’s got four children, you know, he’s a [widower], and I’m married. And if [I] leave, who is going to take care of the kids. So I told Commander about it.”

“So he said, ‘Okay. If you don’t want to be transferred to Hagåtña, so go ahead and do your job, midwife.’ ”

“So I did it. Then later on they transferred the hospital again [to] right where the hospital [was] before in Hagåtña, and they built another hospital there. My God, if it’s not [for] my [disabled] son, I think I am going to keep working in the hospital because that’s my job. I like to be a nurse.”

“I worked for 16 years as a midwife.” (This was from 1942 to 1958, and all those years were spent in Agat.) “All those children that I delivered, whenever they met me, they hug me. ‘Oh, Mrs. Herrera, thanks so much for helping us and my mom.’ ”

“ ‘Okay. No problem because that’s my job.’ That’s my favorite job, to help people. [People came to the house] day and night, day and night, but I never get tired. Sometimes two or three [people a day], at night too.”

“[They are] all in my record book where I’m putting all my deliveries, but it was destroyed in Typhoon Pamela [in 1976]. When my ranch [fell] down and also the dresser, all my records in my dresser are [damaged]. It’s all wet. I know I still got my record in the hospital for delivering babies. They’ve got certificates [for registering births] to write it down, every delivery, report it in. And I’m paying taxes for that. It’s a good job. Once I [report] my delivery, [the government] knows [the people] are paying me. And I’m afraid not to mention it because I don’t want to be punished. Every delivery they pay me. It’s suppose to be 25 dollars for each delivery, but as for the people that appreciate my work, sometimes they give me 50 dollars, sometimes they give me 35 dollars. But by the law, it’s only 25 dollars.”

“The chief sends the [certificate of birth to the hospital] by the corpsman. Every time I need to go to [turn in] my report or do something at the office, [the corpsman] took me by jeep. You know, sometimes, my husband almost tried to get jealous of me [with] the corpsman.”

“I said, ‘Forget it.’ I’m old enough to take care of myself because I was thirty years of age at that time.”

“The parents’ feeling about their daughter [is] not to let them [become a] nurse; they don’t [have] trust [because of] the American people there, the corpsmen. But my mother allowed me. She wants me to help people. She’s a good mother, understanding of what I’m saying, that I want to [become a] nurse, because I want to be a midwife. I want to do that job. So she allowed me.”

“I remember how many [babies I delivered]. I think more than 200. We had two midwives in the village, but most of the time they call for me. They like me. You know, I never [had it] happen that a mother [or the baby] died in the house. Because as soon I reach the house, [I] get the blood pressure and everything checked [with] the mother. And if I knew that they had high blood pressure, I never allow them to have [the baby] at home. I never. I explain to the mother that ‘I want to help you, so try and [follow] my decision, and go to the hospital because that is the place where they can help you out.’ And there is no problem for me.”

“So they said, ‘Well, I will go to the hospital as long as you go with me.’ ”

“I said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it.’ ”

“I used to go in the labor room, put [on a] gown and everything, and help because the patient wants me along.”

“Every two, three months I went to get my [midwife] supplies. I had a basket prepared for whenever someone comes to call me to deliver.”

“I always [follow] the rules. Yes, to have your license you have to be very strict and do a good job. Don’t [take] a chance [and] delay the patient at home if you know that it’s not going to be a normal delivery. So I never did that.”

“Most all the time I leave Agat without my husband knowing that I’m in the hospital. I always do that. When I reach the hospital, then I call [to] Agat at the police station to look for my husband to notify him that I am there.”

“There’s one of my brothers staying with my family. That’s why I [was able to do] this job. I trust [him]. He helped me a lot. I couldn’t even pay for whatever he [did for] me. [My husband] died November 20, 1983. He’s a good husband, no matter he’s older than me by 14 years. And I was just thirty years old when I married him.”

When Tan Kina’ was asked if there is anything she would change if she had to do it over again, she said, “I don’t think so. I’m not going to change. I’m going to do it the same as before.”

As for advice for young people today, Tan Kina’ says, “You have to have a good education, you have to prepare. And if you graduate, I hope one of you will do it the way I used to do it-to be a nurse-because that’s good help for the family, and to help people.”

Comments

In 1996, Tan Kina’ undertook the task of recreating a list of the names of the women she had assisted during childbirth and the number of children born to each. She did this to verify the number (200 births attended) that she had given during the interview. She also has copies of two of her licenses to practice, which were issued in 1947 and 1956.

Tan Kina’ died on July 21, 2007.

Tan Ana M. Rosario

Estorian Tan Ana M. Rosario (Interview conducted in December 1995)

| Full Name | Ana Mendiola Rosario |

|---|---|

| Better Known As | Tan Ana Kala’ or Tan Ana Siboyas |

| Date of Birth | 8 January 1919 |

| Parents | Father: Juan Laguåña Mendiola; Mother: Ursula Cruz Aquino |

| Siblings | Youngest of seven children; five brothers and one sister (all deceased) |

| Husband | Pedro Taitingfong Rosario (deceased); married 1942 |

| Children | Reid, Evelyn, Marie, Pedro (deceased), Joseph, Juanita, Elizabeth, and John Michael |

| Education | Ninth grade; nurse-midwife training |

| Residence | Barrigåda since 1941 |

The Interview

Tan Ana is the only Navy-trained nurse-midwife who, as of this writing, is still seeing pregnant women and providing them massage and advice. Her training started in the hospital and included working in the operating and delivery rooms. She liked the delivery room work and therefore pursued mid-wifery training as well. “I like to join the midwife [program],” she says. “If somebody is going to give birth, I have to go and help.” After the hospital training, she was assigned to assist with births outside of the hospital.

Tan Ana says, “I help the people outside, to give birth in the jungle, in a carabao cart covered with a floor mat, or sometimes they cut coconut leaves and put it on the ground. [I] went to every village [where] they want me. I go to Umatac, Merizo, Inalåhan. That’s why I am well known, because I always go everywhere and my husband sometimes go with me because [it’s] midnight [or] 2 o’clock in the morning [when] they call me to go. They contact me; so they just come [by] car that time. My husband said, ‘Never mind, I’ll take my wife.’ [We] had a car, a Jeep.”

Differences in methods of delivery were noted during Japanese times. Tan Ana recalls, “They give me one nurse, a Japanese nurse. I don’t [know] how they do it to give birth because they stand and push [the pregnant woman’s] stomach down with [their] feet. So I tell them not to do that because we are not doing it like that when [we] help the people. So I teach them how to take care of the patient.”

Sometimes in responding to a request to assist a woman in childbirth, the nurse-midwife found she was required to be away from home for several days. Tan Ana says, “Especially when they call me to Umatac or Merizo, I have to stay three days there because there are plenty of pregnant ladies there. If they are ready to give birth, I cannot go and I have to wait until that time [to give birth] comes.”

When asked how she managed her work and children, she replied, “My children are big already. My mother is the one taking care of my children. We are staying at the ranch.”

Midwifery work was very satisfying for Tan Ana. She says, “The patients like me because I am very kind to the patient and I do everything, whatever they want me [to do], to stay or wait until the sun is up. Sometimes I stay all night.” Tan Ana says she assisted only with normal births. She explains, “I have my stethoscope, my blood pressure [apparatus], and the medicine they, the hospital, allowed me to use for the patient. I have to take the blood pressure first and, if the blood pressure is high, then I convince the patient to go to the hospital. Because in case there is a hemorrhage where are we going to get the blood outside [of the hospital]? So I say, ‘Let’s go, I’ll take care of you at the hospital.’ So I take the patient to the hospital [and stay with her] until she gives birth and everything is okay. But outside, I don’t take a chance.”

The patient’s financial circumstances were considered when compensation was accepted. Patients gave whatever they could. Tan Ana added, “And if I know they have plenty more children than I do, so I better [return] that money, and they give me three chickens or one small pig. My husband said, ‘If you see that the patient [has] plenty children, then don’t take anything.’ ”

The midwives were licensed. Tan Ana states, “We have to go to the hospital and get information from the doctor [the one who does deliveries]. So if they give me authorization to go, I have to go to the government and ask for my [midwife] license.” This was done every year. “When the baby [is born], I have to [fill out] the birth certificate and take it to Public Health. During the time [of Japanese occupation], they did not have any paper to give out [for birth registration], so when they have the paper ready, they notified me [to] fill in those papers. During that time, 1941 and 1942, we just delivered and that’s it. At that time I can [deliver] three to four patients in one day.”

Women were also seen before the time of delivery. “I have to check [the pregnant woman] first,” says Tan Ana. “Three or four days [before the birth] they come over and ask me to help them, to check whether the baby is normal or what. Then after the delivery I always go and check the umbilical cord, and until that day [that] she goes out [of the hospital], that’s the time I discharge the patient, sometimes five days, four days. If I help somebody give birth in Umatac or Merizo, so every other day I went with my husband to check the umbilical cord, and [if] something is wrong with the patient, they have to notify me. Nowadays they always come over and check [with] me [whether] she has breech presentation. They come over to have massage. This morning I finished four already. There’s a lady that has flu, so I told her to go see the doctor because the flu is no good for the baby. I stopped [going out] in 1986.” This was the same year that Tan Ana’s husband died.

To help somebody is what made Tan Ana happy. “Sometimes, in 1944 to 1950, patients would give birth in my house. I always change, over three times, my bed, the mattress, because when she is lying down the water comes out. So I called the ambulance and [the patient is taken] to the hospital. I talk to the patient [about] what they are going to do and [the position of the baby]. So if you listen to me, you are going to give birth at the hospital fast. [There was a patient] here last week, [and] the doctor didn’t know the patient was going to have twins, so the patient says, ‘Doctor, I’m going to have twins.’ You know, she [had] a big baby. So when she gave birth, this is a miracle to have two babies inside,” laughs Tan Ana.

“They were training us at the hospital, the old Guam Memorial Hospital, in 1960, in the OB [obstetrics] room,” says Tan Ana. Since then no further training was offered to the midwives. “Now there is a doctor that always talks [to patients] about me at the hospital. Sometimes [the doctor] says, ‘I have plenty patients and I cannot tell if the baby is a breech presentation. Go see the old lady in Barrigada and ask what’s wrong with your baby.’ [The doctors] are very nice if I went over to the hospital and I checked the patient. They’re very nice to me. You know what? If a patient always comes to me, and I tell her what’s wrong with [her], and the doctor says your baby is a breech presentation, the placenta is farther than the baby. And, if the placenta is still down below, the doctor will give her a Cesarean (section). I show the patient about the baby, how the baby is inside.”

Tan Ana took out a textbook with colored pictures showing a baby’s progressive development in the uterus. “So if you don’t take care of yourself, the baby will go, you lose the baby,” continued Tan Ana. “If the patient wants to see [how the baby looks] when she is ready to give birth-if the patient is not scared-I can show [a picture of] how the baby is inside. So when the patient is ready to give birth, I tell her to drink water and sugar because the placenta will go back to its place. And this is the time when the baby is ready to come out [and] the baby is in normal position. But when [the baby] is not in normal position, sometimes breech presentation, that means something is wrong with the baby. So they come every day; they come to check with me to help the baby.”

At the end of the interview, Tan Ana attended to a pregnant woman who had come for a massage to relieve the back pain she was experiencing. This was the fifth woman to seek Tan Ana’s help on the morning the interview took place.

Comments

Tan Ana trained for three years. Her midwife license expired in 1955. Tan Ana died July 31, 2003.