Interpretive essay: Rich historical heritage

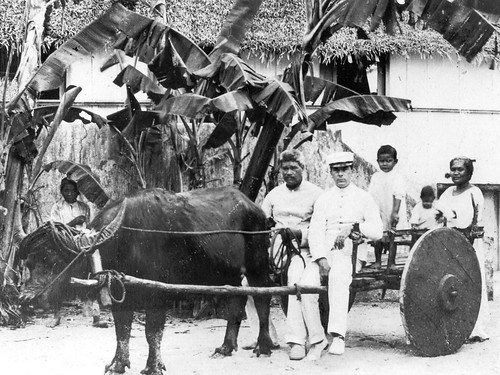

Captain Henry Glass’ bloodless seizure of Guam on 20-21 June 1898, his quick departure without establishing an American take-over government, and even the tears of the last Spanish governor – Juan Marina – who was overwhelmed with the kindness of Lieutenant William Braunersreuther for not looking at the letter Marina penned to his wife as he and other Spanish officers were taken away to Glass’ ship in a sudden downpour, are all part of the complex historical and contemporary consequences following this commencement of the early American period of Guam history.

Each event, and certainly much more from that moment of Glass’ arrival at Apra Harbor, constitute the historical heritage of this period which has particularly profound implications for the CHamoru people. The perceived largeness or smallness of each event and detail is riveted in a process of historical interpretation, remembrance, or the lack thereof based on equally complex processes of acculturation, indigenous appropriations of outside sources in a communal context, and the expression and assertion of contemporary cultural identity and self-determination.

By the time Japanese forces invaded Guam in the pre-dawn hours of 10 December 1941, seized the historical Plaza de España in Hagåtña that was defended for a short time by vastly outnumbered Marines and a small Guam Insular Force (which remains a source of pride for the CHamoru people), committed atrocious acts of violence against the CHamorus during their occupation of Guam, and were finally defeated by invading American forces in July 1944, the CHamoru people had experienced many changes and challenges.

Influential CHamoru priest Father José Bernardo Palomo y Torres (Spanish Governor Luís Santos complained that no government order was obeyed until the CHamoru people had consulted with Father Palomo) helped CHamorus cross the bridge from Spanish to American control of their island. Father Palomo, with his multiple languages and devotion to his parishioners, would remain an important source of advice for the all-powerful Naval governors.

Despite their reliance on Father Palomo, early American governors nevertheless sent forth proclamations to forbid the ringing of church bells (“after the issuance of this order, Lieutenant [William E.] Safford saw numerous natives who possessed no clocks huddled before the church door between 2 and 3 a.m. so as not to miss the 4 o’clock Mass”, whistling in Hagåtña streets, land sales without the governor’s permission, public Catholic processions, and raised taxes on land that often led to its loss. Father Palomo defiantly began ringing the church bells at irregular hours.

And in a different time, but still within the American period, a courageous Father Jesus Baza Duenas would defy Japanese officers on Guam, refusing to allow the church altar to be used for Japanese propaganda and criticizing the actions of state-sponsored Japanese Catholic priests. He openly criticized the cruel treatment of CHamorus by Japanese troops until he was imprisoned, tortured, and killed days before American forces landed to fight bloody battles to seize Guam and use it in a final push toward Japan itself. At the same time, Private First Class Radioman George Tweed, the only surviving American hiding on Guam during the 10 December 1941 – 21 July 1944 Japanese occupation was being picked up by an American ship – his survival completely dependent upon the sacrifices, beatings, and deaths of the CHamoru people who protected him.

The beginning of this US Naval Era with these inklings of history (and much more) is often portrayed in comical terms, given the fact that no one on Guam – CHamoru or Spanish or anyone else – was aware that Spain and America were at war with each other. In 1898, communication was slow and news traveled on the graces of ship captains who irregularly reached Guam from the Philippines. Commonly cited is the firing upon the abandoned Fort Santa Cruz by canons of the USS Charleston. The only recorded reaction was by two fishermen who frantically paddled away in dugout canoes although a group of Spanish officials conducting inspections of foreign ships sent for two small canons to be brought from the capital of Hagåtña to return what they thought were salutes from Charleston’s crew. The American crew were mainly rural young men who days before had been treated to picnics and outings in Hawai’i and, having practiced shooting the cruiser’s guns on their way to Guam, were prepared to battle thousands of nonexistent Spanish troops on Guam where they thought death was probably inevitable.

A small boat of prominent Guam residents rowed out to the USS Charleston. They became the first people on Guam to learn of the Spanish American War. Although they could not have known it, the commencement of an American presence would have a profound impact on Guam for 100 years and counting – an impact that is not only open to historical questions of degree, form, and substance, but also open to questions of loss or, rather, the controlled appropriation of American forms of influence back into the fold of CHamoru society. Left behind by Captain Glass were prominent citizens who grappled for government control against the remaining Spanish Treasurer, Jose Rodrigo Sixto.

After at least 230 years of Spanish control (the last Spanish battle with CHamoru resisters is typically designated as the one on Aguijan in 1695), CHamorus momentarily seized the opportunity for self-governance that was forced to change every few months as a chance Commander arrived at Guam before the first American Naval governor Richard Phillips Leary finally arrived a year and a half later. On 1 January 1899 several pro-American leaders, including Father Palomo, dismissed Sixto and replaced him with Venancio Roberto as acting governor.

It was a short-lived tenure for Roberto – not quite as long as it took to walk across the Plaza de España with a plan to eject Sixto when bells announced the arrival of an American vessel whose captain, Vincendon L. Cottman, reappointed Sixto. Sixto had however already nearly drained the treasury, advancing himself and a few others 18 months advance pay. Barren P. Dubois, assistant paymaster of the Bennington commanded by Captain Edward D. Taussig, eventually dismissed Sixto upon discovering his usurping of the treasury.

Dubois appointed three CHamoru men in the only (albeit brief) allowance by US authorities for CHamorus to govern their own island until the one year appointment of publisher Joseph Flores in 1960. (An elected governor would not appear until 1971 when Carlos G. Camacho became the island’s first elected governor in at least 300 years.) They were Hagåtña gobernadorcillio Joaquín Pérez y Cruz, Vicente Herrero as head of the island’s finances, and Vicente Pérez as secretary. They were backed by an advisory junta of several other CHamorus.

The next unknowable arrival of an American commander upon the horizon was Lieutenant Louis A. Kaiser who lived for a short time in Hagåtña, repeatedly repelling requests from passing Spanish ships to collect Spanish medical supplies and arms as per the recently signed Treaty of Paris. When Acting Governor Pérez finally allowed Spaniards to take their supplies, Kaiser dismissed Pérez and replaced him with Samoan-American William P. Coe whose governorship lasted a little over two weeks. In response, the CHamoru leaders created the island’s first legislature with an upper and lower house that Kaiser promptly rejected.

Not until after several decades of typically two-year period American Naval governors, each with their own sense of colonial governance along with a purely advisory Guam Congress, would Guam have entirely elected executive and legislative branches of government. Meanwhile American hegemony in many forms throughout this history – some racist and some more subtle but all resident in historical documents – would seemingly lead to the Americanization of Guam.

School children marched in military form, early public health officials walked through CHamoru villages with the authority to fine violators of “sanitation,” compulsory (and very distasteful) hookworm treatments for children became routine, “lepers” were confined to a beach area in Ypao now used by swimmers, joggers, and barbeque gatherings and, in 1912, were marched all the way to Apra Harbor through the capital city of Hagåtña to permanent exile in the Philippines. Most were never heard from again. (“It made one think either of a circus parade or a big funeral,” Governor Robert E. Coontz would later write in his memoirs.)

The exile of the “lepers” underlined conflicting notions of colonial and indigenous concepts of family and caring as relatives continuously violated restrictions to gain access to kin in the camp. According to historian Anne Perez Hattori, the CHamoru word for the disease – atektok – could be translated to mean “to hug each other”. Naval officials dreaded the disease and, pushing the fear of Americans being infected by leprosy, successfully obtained Congressional funding for the confinement and “treatment” of “lepers” although most of the money actually went for other unrelated government projects and purposes.

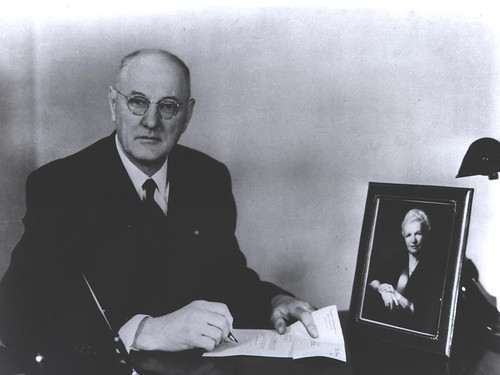

Governor Willis W. Bradley, Jr. (1929-1931) would be the only Naval officer to attempt to push civil rights for the CHamoru people through a Bill of Rights that was ignored by federal officials although some elements were incorporated into revised 1933 Guam law codes.

In an apparent attempt to assuage local feelings of exclusion, Governor Roy C. Smith established the Guam Congress in 1917 although it had no authority and was wholly advisory. However, when its first session was called to order by Governor Smith on 3 February 1917, the first representative to speak, Tomas Calvo Anderson, immediately criticized the Naval government for espousing the ideals of democracy without practicing it among the Guam populace.

Thereafter, the Guam Congress, remaining only an advisory body throughout its history – even after the devastation following the 21 July 1944 US invasion and the ensuing bloody battles with Japanese forces – became a representative body that subsequent Naval governors could listen to or ignore at a whim. Work done by the Institute of Ethnic Affairs in Washington DC led by John Collier, the husband of anthropologist Laura Thompson who had done extensive prewar field work on Guam, a degree of sympathy from elements of American society, and the 1949 walkout by frustrated members of the Guam Congress finally influenced the Congressional passage of the 1950 Guam Organic Act that granted the island a civilian government and a semblance of self-governance supplemented later by the Guam Elective Governor Act in 1968. The Guam Organic Act continues to structure the government of Guam today.

Probably shortly after the two fishermen frantically paddled away but certainly while Glass’ men were demanding the Spanish surrender of the island as eager young fighting men waited on the Charleston, Spanish Augustinian priests, according to Hattori, indicated that “the entire populace became very alarmed and their great distress was very evident…

A large number of devout families flocked to the church, fervently and tearfully beseeching God to put an end to this calamity.” But instead, using (perhaps unconsciously) contemporary measures and means of communication that, lacking in 1898, left an island in the dark about a world stage event that directly affected it, historians commonly prefer to point out the comical side to the beginning of a historical era on Guam that continues today.

Eventually American patriotism and loyalty (particularly evident during the Japanese occupation of Guam) would also become factors of historical interpretation. Patriotism as the result of American hegemony (that included at one point, financial punishment for speaking the CHamoru language), as the result of intermarriages, as the result of things Americans or/and the result of gratitude for the sacrifices of American soldiers as they liberated the island from Japanese control and many other historical events – all have their place in how lives lived in this “American period” have come to absorb this concept.

At least in terms of how history attempts to shape how American patriotism or loyalty exists among a large section of the island’s population and doesn’t exist among a smaller one. But like other societies that have appropriated outside forces and sources on their own terms, Guam’s culture and society merits an understanding on the basis of unboxed notions of how history and historical factors and events have influenced this island’s contemporary society. And there are many of these factors in Guam’s rich historical heritage, each with its unique standing of importance for individuals, including even the tears of Juan Marina.

By Nicholas J. Goetzfridt, PhD

Videos

Featuring clips from the Governor Willis W. Bradley Film:

For further reading

Cogan, Doloris Coulter. We Fought the Navy and Won: Guam’s Quest for Democracy. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008.

Farrell, Don A. The Pictorial History of Guam: The Americanization 1898-1918. 2nd ed. Tamuning: Micronesian Productions, 1986.

Hattori, Anne Perez. Colonial Dis-ease: U.S. Navy Health Policies and the Chamorros of Guam, 1898-1941. Pacific Islands Monograph Series 19. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004.

–––. “The Politics of Preservation: Historical Memory and the Division of the Marianas Islands.” Micronesian Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 5, no.1/2 (2006): 1-4.

US Navy Department Office of Records Administration. American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 1898-1902. By Henry P. Beers. Washington, DC: DONRA, 1944.