American-Style Colonialism

Table of Contents

Share This

Interpretive essay: Colonialism - then and now

Colonialism is a process of usurping an existing order or orders of meaning for a territory or a people, and replacing them with a new order which is defined by the colonizer at that order’s apex. The intended result is that the colonizer will from then on be understood as the source of the colonial world’s order, and the source of any potential progress. Upon entering these spheres of influence CHamorus/Chamorros would find a place already waiting for them, an identity, a place in the world that defined them through racist assumptions.

The cost of entering these spheres and making use of them was quite high. It meant enduring a constant ideological barrage, instructions, lessons, declarations made by the naval government and its representatives, and that CHamorus were dirty, backwards, primitive, unable to take care of themselves, and needed America to save them.

Guam has been a colony of the United States since 1898. At different times, the everyday presence of the colonizer has varied, from being almost invisible to being omnipresent. In Guam today, it is often easy to forget that the island remains a colony. Anyone born in Guam is an American citizen. Guam residents have American movies and television, and learn about all aspects of American culture, history, philosophy, politics, economics and more in Guam schools. Guam is called “America in Asia,” “Where America’s Day Begins,” and even the “Tip of America’s Spear.”

We live in a time where the colonial status of Guam is very difficult to perceive and much easier to overlook or ignore. On the surface it appears as if CHamorus are as American as apple pie. But in a far more fundamental way, Guam is still a colony, subject to the rule of the US and its military, without any reciprocal representation.

The genesis of Guam’s political status is in a time when American colonialism was at its most explicit and unapologetic. The US and its representatives in Guam, the Navy, made no pretense about Guam being part of America. Instead the US treated Guam and its indigenous people, CHamorus, as objects owned by the US.

This period of Guam’s history is known as the US Naval Era or the American colonial period from 1898-1941. A second American colonial period was just after World War II, 1944, up until the Organic Act was signed in 1950. And whereas now the island seems comfortable as an American colony, Americanization during this period was something regularly forced into the lives, mouths and minds of CHamorus.

Material improvements, identity attacks

Although the historical record differs regarding what type of impact this period had on CHamorus, there is clear agreement that it represented a huge shift in lives, for better or for worse. During this period, Guam was run as if it were a military base, or more aptly a US Naval base. The executive officer was a US Naval governor appointed by the US Navy, and he was given carte blanche over the island. CHamorus were not US citizens, rather US nationals. They did not have representatives in the US Congress or any votes for president. They did not have the right to jury trials or to any judicial appeals process.

Older historical writings glorify this period as one of incredible advancement and progress, with America benevolently teaching CHamorus. Through the American control over Guam and the programs that it instituted on the island, CHamorus are brought into the modern world and bestowed the gifts of that world. Paul Carano and Pedro Sanchez’s text, A Complete History of Guam characterized this period as one in which:

…giant strides were made in terms of economic and political development. By 1940, substantial improvements had been made in Guam’s economic life, its health and sanitary conditions, its judicial and educational systems, and in various other departments and agencies of government.

More recent histories such as Colonial Dis-ease: U.S. Navy Health Policies and the Chamorros of Guam, 1898-1941, by CHamoru scholar Anne Perez Hattori, PhD, however, provide a much more nuanced and less stellar account of American colonialism. Hattori and other historians of the modern day mark this period as one of incredible racism and often irrational control of CHamoru lives. CHamorus were wards of the US Navy, devoid of any political protections or inherent rights and simply something to be molded by the United States. Not since the postwar period of the Spanish-CHamoru wars were CHamorus the victims of such sustained attacks on their language, culture and identity.

Why America came to Guam

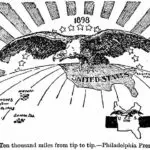

The colonial nature of this time in Guam’s history has everything to do with why Guam was taken by the US in the first place. This period of America’s history represents its expansion into a global power. After subjugating the indigenous people and their lands within what is now the contiguous US, there was a growing desire in the US, especially among its political and economic elites, that America had a “destiny” to expand its power and share its style of government across the oceans, across the world.

Incursions in Asia, Latin America and the Pacific throughout the nineteenth century were all prelude for the largest and most explicit imperial acquisition of the US during this era, the Spanish American War. Guam, along with Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines were all taken as spoils of this war in 1898.

Whereas acquiring large island groups such as the Philippines was due to the economic potential involved, Guam was taken for purely strategic reasons and as a nautical link, a transit site through which American economic and military power could be linked to emerging Asian possibilities. Guam was taken because it offered the largest deep-water port in the Western Pacific. And so Guam, along with other American controlled islands such as American Samoa, Midway and Hawai’i that stretched across the Pacific, guaranteed the US a smooth route of commerce and military resources from America to Asia.

This military value of Guam as a strategic geopolitical location in order to build its power base in the Asia-Pacific region is crucial to understanding US policy to the island and its indigenous people, first during this period, but even up until today. During the pre-war period, as Guam was just a transit site, American policy and investment to the island was minimal, it was a site to be controlled and held but nothing more. Guam would thus become the ”USS Guam” with naval officers and governors at the helm and CHamorus forced along for the ride, and treated like an afterthought on their own island.

America’s colonial rhetoric

This military strategic claim to Guam was downplayed in the rhetoric that the US Navy would use in its colonization. In US President William McKinley’s 1898 directive “Instructions for the Military Commander of the Island of Guam,” which authorized the seizure of Guam this was made clear when he extolled the first and future military commanders of Guam:

…to announce and proclaim in the most public manner that we come, not as invaders or conquerors, but as friends…win the confidence, respect and affection of the inhabitants of the Island of Guam … by proving to them that the mission of the US is one of benevolent assimilation.

Guam’s first US naval governor, Captain Richard Leary, further articulated the colonization of Guam as part of an effort to protect and maintain:

the well-earned reputation of the American Navy as champions in succoring the needy, aiding the distressed and protecting the honor and virtue of women.

Thus efforts would be made to rapidly introduce American ideas and principles into Guam to help elevate the status of the CHamoru people. It should be noted that this sort of rhetoric is customary in the cases of all modern colonizers. The taking over of another’s land, and the re-directing and dictating of their future are acts that require some justification in order to disguise what might otherwise be racist or violent interventions of control as necessary or benevolent acts.

This typical civilizing rhetoric in colonialism, whitewashes the crass and sometimes cruel interests of the colonizer, and makes it appear as if the colonized are the ones who need and who will truly benefit from the colonization of their lands. So, in the case of Guam, the purpose of the US in being there has nothing to do with controlling the island by turning it into a key military outpost. The colonizing rhetoric masks the underlying racist, militaristic and imperial intentions, instead insinuating that the US is in Guam to help the CHamoru people. It is there to lift them out of the squalor of their ignorance and backwards ways, to clean them up and make them modern, and of course to teach them the glories of American democracy and the American way of life.

This rhetoric masks the self-interest of the colonizer at different levels as it masks their purpose in being in the colonies. But it also masks some of the other reasons for colonization and that is to relieve what Hattori refers to as “colonial dis-ease.” As early Guam Naval Governor George Dyer put it, the civilizing of the natives was first and foremost a project of American “self-interest” in Guam. “Civilizing” the natives was something that the US Navy had to do to protect itself, from the various threats that the CHamoru posed in corrupting the American presence in Guam to include the diseases in Guam jungles, in CHamorus themselves and the primitive ways of their culture. All of these things represents sources of “dis-ease” for the naval presence, and the civilizing of the CHamorus was at its core about relieving this fear.

As in all colonial situations, the gap between the rhetoric and the reality can be incredibly stark, and this period is no exception. The lofty rhetoric of societal improvement and advancement was realized in some ways in Guam, but at a more fundamental level, this period was one of control, discipline and hypocrisy, with CHamorus trapped between the promises of American democracy and liberty and the incessant demands of American military and national security interests.

Changing of the colonial guard

CHamorus engaged with their new colonizer in suspicious and cautious ways, for a number of reasons. The transfer of power between the US and Spain was a non-violent one, primarily because of the relative unimportance of the island to the Spanish.

So although there was no outright violence, CHamorus still had much uncertainty about what to expect from their new colonizer. Among the more privileged sectors of CHamoru society, this changing of the guard was particularly upsetting. There were CHamoru families who enjoyed great power or advantage under the Spanish and so the arrival of the Americans potentially meant a loss of status for them, or loss of a colonizer that they had build a deep affinity with. In their minds, the Spanish with their roots in Europe were far more sophisticated than the vulgar Americans. Some families shed tears when the Americans took over, and some even left the island for the neighboring Mariana island of Saipan or even Spain.

There was still much concern and fear even among the non-elite of Guam. According to Jose Garrido who was a 16-year old member of the Spanish Garrison in 1898, many families upon hearing that the US had taken over the island fled into the jungles. According to Garrido:

Were the people scared? I should say so. I learned of an expectant woman who gave birth right then and there. Lt. Lorenzo Franquez fainted while the soldiers were being disarmed.

Jose Garrido

First response to America

The majority of CHamorus in Guam lived not in fear of the military might of America, but rather its tradition of depraved behavior on the island. By 1898, the bulk of CHamoru interactions with Americans had been through bayeneru (whalers) who made port in Guam. In the minds of CHamorus, Americans were most closely associated with the immorality, drunkenness, aggression and sexual promiscuity of these whalers. According to anthropologist Laura Thompson, prior to 1898, CHamorus closed their houses up tightly, with all the women secured safely inside whenever Americans (whalers) arrived on island. Their behavior was so notorious on island that many CHamoru mothers would frighten children with stories that Americans would “get them” if they were naughty.

CHamorus suspicions, while inaccurate, proved to be appropriate. Despite the flowery rhetoric of improving CHamoru lives and partnering with them as friends and not conquerors, the true basis for American colonization was made very clear in the orders given to the island’s first Naval Governor Richard Leary:

The needs and desires of the (US) military in Guam take precedence over all matters in the administration of the island.

Naval interests superseded any guarantees that US citizens received under the Constitutions—but then again, CHamoru rights, such as the right to religion, were never enacted in Guam – as exemplified by the banning of church bell ringing, processions, and feast days by naval administrators.

CHamorus sign petition

Groups of CHamorus were quick to respond to the establishment of this autocratic regime, with a petition signed on 17 December 1901 calling for an end to military rule in Guam and the establishment of a civilian government. The more than two dozen signatories of this petition came from the wealthiest and most educated sectors of Guam society, individuals who had been privileged under the Spanish and had the resources to be very successful under the Americans as well. The tone of their petition is respectful, but firm in noting the hypocritical nature of American rule in Guam:

A military government at best is distasteful and highly repugnant to the fundamental principles of civilized government, and peculiarly so to those on which is based the American government.

It is not an exaggeration to say that fewer permanent guarantees of liberty and property rights exist now then when under Spanish domain. The governor of the island exercises supreme power in the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government, with absolutely no limitations to his actions, the people of Guam having no voice whatsoever in the formulation of any law of the naming of a single official.

This petition was transmitted to the US Congress and the US Department of the Navy, but ultimately fell on deaf ears and nothing was done to change the governance of Guam for several more decades. The importance of this document however is that it provides the foundation for how we can understand the ways in which CHamorus understood their relationship to the US during this period, and, more importantly, how they understood themselves in relation to its colonizing efforts on the island and its rhetoric of benevolence. It helps us realize that CHamorus of this period were neither “dupes,” nor uncivilized children, but rather intelligent beings who saw America for what it was, a colonizer.

According to Penelope Bordallo Hofschneider in her text “Campaign for Political Rights on the Island of Guam: 1899-1950”:

The document [petition] is also interesting because it suggests that the native people viewed their political relationship with the United States as essentially a colonial one…There is no doubt that so far as the CHamoru people were concerned, the Americans simply filled in a position established and held by the Spanish for 250 years…America simply represented a new and perhaps, a more liberal ‘Mother Country.’

This petition was the first of many more throughout this period that were sent to the US military and US Federal Government with hopes of bringing about a change in Guam’s governance to something more democratic or equitable. Each of these petitions would be denied or ignored, generally on the understanding that political rights for CHamorus would jeopardize the US Navy’s ability to perform its military mission in Asia.

Haphazard colonialism

When it came to the actual governance of Guam by the US during this period, to call it “haphazard” would be a very generous qualifier. The rhetoric of Guam’s colonization laid out lofty goals for improving Guam and the lives of CHamorus, but the implementation of these goals required financial support and leadership. All of these conditions varied wildly during this era, in particular during the first two decades of naval rule.

Guam's resources

Although Guam was important to the US as a key nautical link, this value at the beginning of the 20th century was still unappreciated, reflected in the Navy’s inability to secure funds or resources for Guam’s militarization. In contrast to the strategic importance of Guam today, the island was, prior to World War II, a site to be “possessed” and little more. Thus any plans that the Navy might have had for improving the lives of CHamorus were severely hampered by what they could afford.

Part of the Navy’s insistence that CHamorus become savvier and more mature capitalists was due to these financial limits. The hope was not that CHamorus would progress and grow economically for their own sakes, but rather they expand economically in order to provide a tax base to help support the naval government’s operations, and establish an agricultural workforce to feed their colonizers as well. The Navy’s presence in Guam was so financially inept in its early years, that pesos (Spanish currency) were still the official currency of Guam until 1907.

Even in the 1920s when it was clear that Japan and the US would eventually come to blows over their shared presence in Micronesia and the Asia Pacific region, and that Guam would be caught up in any conflict, the island was deemed indefensible and no extra funds were given to the island to build up its defenses.

Leadership's quality varied

In the minds of most members of the US military, especially high ranking officers, the prospect of being transferred to Guam, or being appointed as the island’s governor was not a good one. In fact, it was considered an isolated and boring post, which symbolized the end of what could have been any promising upwardly mobile career. Thus the incentive to govern Guam was minimal, since it could have been the island itself that killed your career. Furthermore, the tours of duty for Naval governors were incredibly short, some lasting a few months or as much as two years. The naval presence would disappear and replace itself regularly, leaving the government of Guam constantly in a transition phase as new officers and governors came in, replacing those that had left, each new entrant knowing as little about the island as its replacement. Thus while the rhetoric may have always been consistently flowery and self-aggrandizing, the realities of Guam’s colonization and what actually happened or was enacted, depended almost entirely on the personality of naval governors and whether they “felt” like governing the island or not.

Scanning the list of 28 Naval governors during this period, we can find examples across the spectrum of action and inaction. While the majority of Naval governors did little to distinguish themselves in the minds of both CHamorus and history books, there are a few names which stand out above the rest in terms of their engagement with the governing of Guam, and two in particular represent the “bad” and “good” faces of naval governance during this period, William Gilmer and Willis Bradley. Gilmer was known as the governor who was “mashanghai,” or yanked out of office after embarrassing the Navy with his regular abuses of power. CHamorus lauded Bradley for his efforts at getting CHamorus American citizenship. When he was rebuffed, he created for CHamorus a “Guam Citizenship,” which was later revoked by the US Naval Department as well.

Colonial abuses

Despite the benevolent and altruistic rhetoric, the recognition of America as a colonizer by CHamorus was made easier by the daily incursions and invasions that America would take into their lives and homes over the next 40 years. The autocratic government, established by the Navy, gave its governor absolute control over the lives of CHamorus, and this power sometimes made life precarious for CHamorus.

First and foremost on the list of colonial tasks was the eradication of the CHamoru language. The refusal by CHamorus to give up their language was considered to the bane of each and every naval governor. It was something that was tasked to them from the first moments of American governance, as the key to properly civilizing the CHamorus. The main weapon by which this task was thought to be accomplished was through mandatory public education in the English language, with the usage of the CHamoru language banned from all government facilities, including schools and offices. The Navy at one point went so far as to burn books written in the CHamoru language, even one that was produced by US Navy Paymaster Edward von Preissig and printed by the Navy.

This was most difficult on CHamoru children, who found themselves trapped between worlds. The language that they entered school with, the one that they had learned from their families, was prohibited. And for merely speaking CHamoru they could be punished or fined. In the early years of naval rule, the teachers were primarily white military personnel or their dependents, and so these anti-CHamoru policies were easier to comprehend.

But as the American education system in Guam became more formalized and more CHamoru teachers were trained, it became CHamoru teachers who were spanking CHamoru students or washing out the mouths of CHamoru students with soap.

Despite the Navy’s claims to come to Guam and protect the virtue of women, the Navy’s policies towards CHamoru women were far from benign. The morality of Guam’s laws at the time was something determined by the moral compass of each naval governor. One naval governor was infamous for publicly humiliating a woman for her “immoral behavior” by calling the village out to watch her head be shaven. One naval governor made plans to keep women who gave birth to illegitimate children in the “leper” colony in Tumon; fortunately, his plan was never carried out.

In 1919, the naval government decided it sufficiently important enough that they uproot centuries of tradition by making it official policy that CHamoru culture be a patriarchy. According to CHamoru scholar Laura Souder,PhD, “Matrilineage was outlawed…CHamorus were forced to abide by patriarchal notions of descent.”

For thousands of years, lineage and land ownership had been passed down through the mother, but now the father would be considered the head of the household and the head of any family. Without any political protections or any access to the power of the governing of their island, some almost ludicrous policies were enacted.

Perhaps most infamous among these were two of the many naval ordinances imposed by Governor Gilmer. The first outlawed whistling in Hagåtña, an offense for which at least one known CHamoru, Gaily Kaminga was imprisoned. The second, required that each able-bodied CHamoru male bring in five dead rats a month to the government or else face a stiff fine.

Spheres of Naval influence

Due to the limitations of the naval government in terms of resources, manpower and will, the colonization of Guam would extend to the whole island in theory only, but in practice be limited in scope. The colonization of Guam would be concentrated into particular “spheres of influence” determined by geography and occupation/institution. These would be the sites of the American colonization of CHamorus, concentrated in the villages of Hagåtña and Sumai, which housed the majority of the American military presence, and centered on institutions such as education, health care, politics and economy.

Upon entrance into these spheres, CHamorus would be forced to engage with and either accept or defend themselves from the new colonial order that was being asserted. This order implicitly and explicitly argued that CHamorus were nothing, other than an obstruction, an obstacle that stubbornly prevented the progress that America was working to bring to the island. Therefore, as the Navy positioned itself as a civilizing teacher to CHamorus, it crammed its spheres of influences with “lessons” on American greatness and CHamoru inferiority.

In some ways these limitations in America’s colonial project meant that CHamorus would be for the most part left alone or be allowed to negotiate with these new American lessons being forced up them, and decide what to choose and what to refuse. Laws and ordinances would be passed by the naval government covering everything from the composition of people’s yards to the length of girl’s dresses to the prohibition of aguåyente (coconut liquor). The implementation of these laws would require more than just their passing. It would require more manpower than the Navy readily had to patrol all the villages and lanchos of Guam. It would also require that CHamorus begin to see the naval government as a legitimate ruler or authority over their lives.

Government vs. Catholic Church

During this period, one could call the real government of Guam the Catholic Church. At the start of the 20th century, it had far more power over the lives and minds of CHamorus than the Spanish government on island did, or the US Navy. The Catholic Church set the rhythm of CHamoru life and its regular calendar of events and rituals provided CHamorus with a vibrant social life as well as a means for maintaining their kinship ties across the island.

Prior to US colonization of Guam, the Church played the central role in educating CHamorus. However, when the naval government established a public education system, which prohibited any sort of religious instruction and was also riddled with anti-CHamoru language policies, the Catholic Church’s role in CHamoru life was invigorated, particularly in relation to maintaining the CHamoru language. While CHamorus speaking their language found themselves under attack, the Catholic Church provided a sanctuary, much like in their homes or lanchos (ranches), where they could continue to speak CHamoru.

From the earliest moments of American rule, the naval government and Catholic Church were at odds, and CHamorus would often be caught up in their antagonism, and this sometimes built up ill will towards the new regime. The Catholic priests in Guam were not just spiritual leaders of CHamorus, but community leaders and given great influence and power by CHamorus.

At both the beginning and the end of this period, American deportation of Spanish Catholic priests hurt and offended CHamorus. Months before World War II hit Guam in December 1941, all the Spanish priests on island save for the archbishop were removed by the US Navy and replaced with American Catholic priests the CHamorus reacted with sadness and ire. The removal of one priest in particular, Father Roman de Vera, provoked CHamorus, and some foretold that Guam and the US would be punished. In the early days of the Japanese occupation, some CHamorus blamed the US for their horrible plight, and believed that it had been caused by their disrespectfulness towards the Spanish priests.

The Naval government’s relationship to the Catholic Church largely depended on who was Naval governor and whether or not he was Protestant or Catholic. To the governor, the Catholic Church was a clear enemy and rival for the minds of CHamorus. The main weapon that Naval governors used against the Church was support informal or formal, given to the fledgling Protestant missions that were being established in Guam.

Colonial improvements

Despite the racist nature of the American colonization of Guam, it did result in some improvements in the lives of CHamorus. Following the formalization of Guam’s educational system in 1922, Guam had a far more comprehensive and far more organized educational system than ever before, albeit in a colonial form. Modern health care had been brought to Guam with the establishment of a free public hospital, and CHamorus did receive regular instruction in school and in newspapers on how to continue to “clean themselves up.”

The Navy’s interest in building up Guam’s infrastructure did result in significant improvements in Guam’s utilities. By the end of this period, coconut oil street lamps were replaced with electric ones, and Guam’s sewage and water systems, at least in the large villages, were all vastly improved. The island’s traditional transportation system, made up of numerous bull cart trails, had slowly been paved over. By 1941, Guam boasted 85 miles of cascajo or limestone roads, and one asphalt road that connected Hagåtña to Sumai. These infrastructure and utility improvements were all made primarily for the naval government’s needs, but CHamorus benefited from them as well.

Although the Naval government of Guam was far from vibrant or energetic, it was nonetheless much more active at times than the Spanish government had been. The Navy provided the means through which a CHamoru middle class could be formed and a prewar CHamoru entrepreneurial spirit could be nurtured. CHamoru Navy retirees and CHamorus working for the Civil Service did not make enough money to become rich in Guam but were able to start small businesses and live comfortably, and did not need to rely on subsistence farming to support themselves.

The cost of colonization

The primary intent of the spheres of Naval influence, or of the civilizing programs that the Navy instituted were not to help CHamorus, to nurture them, or try to get them to reach their full potential as CHamorus. The deeper purpose of these spheres of influence were two fold; one pro-American and the other anti-CHamoru. And it is in these two dimensions that we can see the cost of this era of colonization for CHamorus.

Firstly, the purpose of these programs was to display to both the colonizer and the colonized the extraordinary capability and promise of the United States. These were meant to be colonial spectacles justifying to all that America was great and has a right, no, rather a mission to be in Guam to help the CHamoru people by sharing its greatness. In this way, these programs were explicitly and unabashedly pro-American.

The other dimension of these programs was that they were sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly anti-CHamoru. They did not just dispense democracy, health care or education, but also colonial ideology as well. Each time CHamorus participated in these programs they were not just proselytized about America’s greatness, but also instructed in CHamoru inferiority, dependence, or even non-existence as a people.

While the Navy offered material improvements, the cost was great, both mentally and culturally. It meant not only giving up your identity, language and culture, but accepting that what you are in this world is nothing. That you didn’t have anything to offer, except that which you gave up in order to follow the American way. This non-existent and offensive place offered to CHamorus by the naval regime was enough to give the majority of them pause in terms of whether or not to accept American rule over their everyday lives.

For instance, while free health care was offered to all CHamorus, its existence was predicated on the need to civilize the native, and eradicate its their backwards traditions and blind them with the glory of modern American medicine and altruism.

Similarly, through compulsory public schools, CHamorus were instructed in the greatness of their colonizer and taught the wonders of its history, government, culture. CHamoru traditions and history were all intentionally kept out of these spheres, or openly attacked as being backwards or something which would hold CHamorus back.

This denigration of the CHamoru people led to resistance. Just as they had perceived the hypocritical and colonial character of American rule over their lives in 1901, the majority of CHamorus interpreted these programs in the same way, with caution and suspicion.

For example, when the 1st Guam Congress was created by the Governor Roy Smith in 1917, the Naval government celebrated this as a huge shift, an event worthy of celebration as an instance of American democracy being passed on to the CHamoru people. These members of the Guam Congress were appointed by the naval governor, and the intent of the new legislative body was- according to the governor- to “make [CHamorus] feel they are taking part in their own government.”

The use of the word “feel” in most instances could be excused, but in this case it pointed straight to the inconsistency of the situation. The first Guam Congress did not represent CHamorus taking part in their own government, as it was only an advisory body and not even democratically elected. It had no power except to make recommendations to the naval governor.

CHamorus quickly recognized the non-place for them in this sphere of influence, they recognized their position as being useless, and not engendering any respect or improvement for themselves. CHamorus quickly lost any interest in this body and it was eventually dissolved. Another attempt to create a similar advisory Guam Congress more than a decade later found similar results, even though in that instance CHamorus were allowed to vote for candidates. According to a Naval history for the period:

The next surprise to the naval administration, so optimistic over its experiment in democracy, came at the general election of 1933. Only about half the 1931 electorate bothered to register. The apathy was so reflected in the candidates that twelve congressional seats were not contested and had to be filled by appointment.

CHamoru responses to American colonialism

CHamorus generally responded to America’s colonization of their island in three ways: assimilation, active resistance and passive resistance. These generalizations aren’t mutually exclusive, and so it is not that each CHamoru adopted only one of these strategies in dealing with American colonialism and never diverted. Rather these were three approaches that CHamorus could choose from, and at different moments they may have moved between them in relation to a particular colonizing effect, or they may have felt the need to assimilate in some ways, but passively resist in others.

Assimilation: CHamorus who chose assimilation accepted the new colonial order. They embraced the rhetoric of the CHamoru denigration and thus saw the purpose of the CHamoru during this era was to do whatever the US asked of them and to find whatever ways they could follow America’s example.

CHamorus who assimilated often times ended up taking up the cause of the colonizer in Guam and sometimes became formal or informal representatives for the naval government. These CHamorus were often promoted in the naval government because of their willingness to write or speak out against the use of the CHamoru language or CHamoru customs.

These CHamorus accepted what the Navy offered them in the new colonial Guam. They further accepted that being a CHamoru offered them no future, and that they would never be allowed to progress so long as they did things “the CHamoru way.”

Resistance Active: This term should not imply that CHamorus were in the streets fighting the US Navy, but rather that their response to the colonization of Guam was an active and critical one, whereby CHamorus organized or publicly made their critiques about their status known and in some cases fought for change.

Those who actively critiqued the US military presence and its rhetoric did so through demands made to the Navy in Guam and the US Congress particularly that CHamorus be given political protections and rights. Three generations of CHamorus signed and disseminated petitions for these protections, but in each instance they were rebuffed.

Two prominent CHamorus, B.J. Bordallo and F.B. Leon Guerrero, journeyed to Washington, DC in 1937 to lobby for a shift in treatment of CHamorus in Guam. They were able to convince US Congress to hold hearings on the issue, at which they testified. They were even able to arrange a meeting with US President Franklin Roosevelt who, much to their chagrin, was far more interested in talking about the fishing in Guam, as opposed to its political status.

Resistance Passive: Rather than make these open critiques, the majority of CHamorus resisted the colonization of Guam in more passive and subtle ways. This resistance was not about open confrontation, but quiet negotiation and avoidance. These CHamorus recognized that the programs of the Navy were antagonistic to them and racist. They knew that the lessons the Navy was trying to teach them painted their people as backwards, but they also knew that the Navy couldn’t simply be ignored or rejected.

Thus these CHamorus would develop strategies for how to navigate the racism of the Navy in its hospitals, government offices, courts and schools, and only do a modicum of what was required of them by the Navy, until they could leave these oppressive spaces and return to their homes.

Just as following the Spanish colonization of Guam, family lands or lanchos (ranches) became bastions in CHamoru resistance and maintenance of their identity and culture, this too held true in the American period. Despite the regular bombardment of colonial ideology, through their homes, their ranches and even at times their religious spaces, CHamorus were able to maintain their language and culture.

Conclusion

The scorecard for the Naval government during this period is an average one in their given tasks to Americanize the island, get people to speak English rather than CHamoru, and radically re-shape CHamoru culture and the landscape of CHamoru life. While they made inroads in their colonization of Guam, molding CHamorus into obedient colonial subjects was far from successful.

The US clearly had an impact during this period. CHamorus integrated much of the new technology and media that came to Guam into their lives. CHamoru, however, was still the primary language of communication for CHamorus young and old, even though English was far more pervasive in 1941 than it was in 1898, as thousands of CHamoru children had gone through the island’s public school system.

But the true measure of colonialism’s success, the reworking of CHamoru identity, had yet to happen in the era before World War II. Despite the haphazard efforts of the US Navy, CHamorus did not truly accept the rhetoric that they were dependent upon the US or that they merely existed to give up everything and follow America. As Robert A. Underwood, Ed.D., (University of Guam professor emeritus and former Guam delegate to US Congress) notes in his speech “Teaching Guam History in Guam High Schools”:

The CHamoru people were not Americans, did not see themselves as Americans-in-waiting, and probably did not care much about being Americans.

Robert A. Underwood

Videos

For further reading

Aguon, Katherine B. “The Guam Dilemma: The Need for a Pacific Island Education Perspective.” In Hinasso’: Tinige’ Put Chamorro–Insights: The Chamorro Identity. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1997.

Bevacqua, Michael Lujan. “‘These may or may not be Americans…’: The Patriotic Myth and the Hijacking of Chamorro History on Guam.” MA thesis, University of Guam, 2004.

Bordallo, Baltazar J. “The Awakening.” Pacific Profile 3, no. 8 (October-December 1965): 34-39, 42; no. 9: 10-13, 25, 37; no.10 24-27, 31, 35-36, 39, 41.

DeLisle, Christine Taitano. “Delivering the Body: Narratives of Family, Childbirth and Prewar Pattera.” MA thesis, University of Guam, 2000.

Diaz, Vicente M. “Simply Chamorro: Tales of Survival and Demise in Guam.” In Voyaging Through the Contemporary Pacific. Edited by David Hanlon and Geoffrey M. White. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2000.

Farrell, Don A. The Pictorial History of Guam: The Sacrifice, 1919-1943. Saipan: Micronesian Productions, 1991.

Hattori, Anne Perez. Colonial Dis-ease: U.S. Navy Health Policies and the Chamorros of Guam, 1898-1941. Pacific Islands Monograph Series 19. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004.

Hofschneider, Penelope Bordallo. A Campaign for Political Rights on the Island of Guam, 1899-1950. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2001.

Nelson, Evelyn. “Dictatorship American Style!” Unpublished article, 1934. Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam.

“Petition Relating to Permanent Government for the Island of Guam. House Document No. 419, 1902.” In I Ma Gobetna-na Guam: Governing Guam Before and After the Wars. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1994.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.

Souder-Jaffery, Laura Marie Torres. Daughters of the Island: Contemporary Women Organizers of Guam. MARC Monograph Series 1. Mangilao: Micronesian Areas Research Center, University of Guam, 1987.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.

Underwood, Robert A. “The Colonial Era: Manning the Helm of the U.S.S. Guam.” Islander (Pacific Daily News), 22 May 1977.

–––. “Teaching Guam History in Guam High Schools.” In Guam History: Perspectives. Volume One. Edited by Lee D. Carter, William L. Wuerch, and Rosa Roberto Carter. Mangilao: Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1997.