Two sources of information

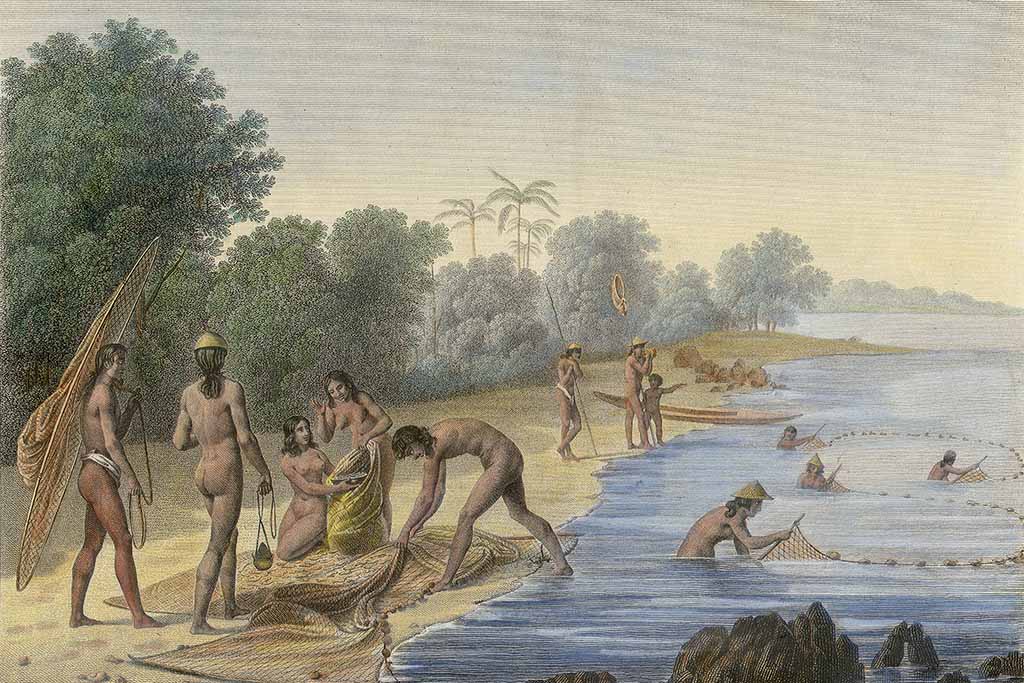

Two sources of information reveal the fishing practices of the Ancient CHamoru people. The first source is the archeological evidence. This includes the actual remains of fishes as well as pieces of fishing gear that are preserved in the ground and excavated by archeologists. The second source is the written record. The early explorers who wrote about Guam after Ferdinand Magellan’s arrival in 1521 invariably remarked on the exceptional sailing and fishing skills of the CHamorus.

Archeological evidence of fishing

When the first people arrived in Guam about 3,500 years ago, there were no large land mammals to hunt, but the ancient CHamorus had an almost unlimited supply of animal protein from the sea. They fished for both reef and pelagic (open ocean) fishes and collected mollusks and other invertebrates, including crabs, lobsters, and sea urchins. They also caught sea turtles.

There is no written record for the prehistoric period in Guam before Spanish contact in AD 1521. Instead archeologists study the archeological record, which includes the artifacts (man-made objects) and ecofacts (natural objects with archeological significance) left in the ground by the people of the past. Artifacts used in fishing include fishhooks, gorges (a type of fishhook with two prongs), composite hook points and shanks, bone spears, and stone fishing weights. Ecofacts pertaining to fishing include the bones, teeth, and scales of fishes; seashells; the durable parts of crabs, lobsters, and sea urchins; and the bones and shells of sea turtles. Faunal analysts identify the fragmented animal remains from archeological sites by using comparative collections.

Parrot fishes are the most abundant fishes found in almost all tropical Pacific island archeological sites, including Guam’s sites. There are two reasons for this. Parrot fish are easy to catch, so they were no doubt abundant in the catches of the past. Also, the mouth parts (parrotfish beaks) are very sturdy, so they preserve well in the ground, and they are easy to identify.

The analysis of fish bones from sites on Guam has revealed that ancient CHamorus caught all of the ordinary reef fishes and even some extraordinary reef fishes, including the largest species of parrotfish, Bolbometopon muricatum (the bumphead parrotfish or atuhong in CHamoru) and the even larger humphead wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus or tanguisson). They also caught potentially dangerous fishes, including sharks and rays, moray eels, scorpionfish and barracudas.

But the most extraordinary fishing done by the ancient CHamorus was from their sailing canoes in the open ocean for mahimahi, marlin and sailfish, swordfish, tuna, and wahoo. Flying fishes (gaga in CHamoru) were also caught from canoes and used as bait for some of these large pelagic fishes.

In addition to the actual fish remains, archeologists have found pieces of fishing gear from the Ancient CHamoru Era. Most abundant are one-piece J-shaped fishhooks and V-shaped gorges made of Isognomon, a kind of oyster shell. These are found at almost all coastal sites. Less common are the composite fishhooks that have separate points and shanks, which were tied together. The points were made of bone or shell. Points of composite fishhooks are more commonly found than the shanks, some of which may have been made of perishable materials, such as wood.

Since there were no large land mammals in the Marianas before Spanish contact, the CHamoru people used human bone for fishhooks and spear points. Human bone spear points were used in fighting, but were probably used as fishing harpoons as well. Stones used for fishing weights are also commonly found in coastal sites. They can be recognized by the grooves surrounding them where natural fiber lines were tied.

Faunal analysts suggest likely methods the ancient CHamorus used for catching fishes based on the technology of the time period, the habits and habitats of the fishes, and ethnographic comparison. Many species of reef fishes were caught with nets. Others were caught with baited hooks. We have reason to think the gorges were used for catching flying fishes. Large pelagic fishes, such as mahimahi, tuna and wahoo, were probably caught with the composite fishhooks. Marlin, sailfishes and swordfishes may have been taken with harpoons.

Early written records concerning fishing

The authors of the earliest written records pertaining to the Marianas remarked on the exceptional sailing and fishing skills of the CHamoru people. Ferdinand Magellan’s chronicler on the first European expedition to land at Guam in 1521, Antonio Pigafetta, wrote that it was the pastime and sport of the men and women of Guam to go out in their canoes and catch flying fishes with fishhooks made of fish bone.

During the period of time between Spanish contact in 1521 and Spanish colonization in 1668, CHamoru culture continued as it had in some respects. The principal change in fishing technology was the introduction of iron, which could be fashioned into fishhooks. By the time the Spanish missionary Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora was in the Marianas in 1602, he said the CHamorus made fishhooks from nails given to them by people on passing ships or salvaged from the Santa Margarita, a galleon which wrecked on Rota in 1601. Juan Pobre also recorded what was told him about the use of a two-pronged shell hook, probably an Isognomon gorge, to fish for flying fishes.

A Spaniard named Sancho, who survived the shipwreck of the Santa Margarita and became the servant of a CHamoru named Suñama at Pago, Guam, visited Fray Juan Pobre on Rota in 1602. Fray Juan Pobre wrote what Sancho said about how the CHamorus fished for flying fishes and used flying fishes as bait for mahimahi, marlin and other large fishes.

Fray Juan Pobre wrote:

When they fish for flying fish, the people of the village gather as a group, then sail out in their boats, each carrying ten or twelve calabashes [gourds]. A very thin cord with a small two-pronged shell hook [gorge] is tied to each calabash. One prong is baited with tender carne de cos [possibly coconut meat], the other with a shrimp or some other small fish. The fishermen put all these calabashes in the sea at the same time, each person watching his own. When the calabash wiggles, it is a sign that a flying fish has been hooked. The people living along the shores of these islands catch so many fish that they have enough flying fish for everyone―like the sardine catches in Spain. These fish are usually eight inches long, although some are twice that size. The first flying fish is eaten raw; the second is baited on a large hook attached to a line that is cast over the stern of the boat. Many dorados [mahimahi], agujas paladares [possibly blue marlin], and other large fish are caught in this manner.

A great fish story

Sancho also told Fray Juan Pobre the following fish story about his master, Suñama. Suñama caught a flying fish and ate the first one raw. With the second flying fish, he baited his hook and hooked a very large billfish (probably a blue marlin) and spent a great deal of time playing the fish to tire it. A large shark came and seized the billfish. When Suñama did not let go of the line, his boat capsized. He tied his line to the capsized boat and followed the line to the shark, diverted the shark, then brought the billfish back to his boat, which he righted and sailed home, flying a woven mat from the masthead to indicate a successful catch. Sancho declared that the CHamorus were “the most skilled fishermen ever to have been discovered.”

Atuhong and tanguisson – The bumphead parrot fish or atuhong is the largest species of parrot fish. It can grow to more than four feet in length and weigh over 100 pounds. The humphead wrasse or tanguisson is the largest species of wrasse. Some tanguisson reach lengths of more than six feet and weigh more than 400 pounds. These large reef species were caught throughout the Ancient CHamoru Era and are still caught today.

East Coast Sites – Archeological sites on the east coast of Guam, including Pagat, Mangilao Golf Course, and Ylig Bay, have yielded collections of fish bones with high percentages of large pelagic (open ocean) fishes, especially mahimahi and marlin. That means the ancient CHamoru fishermen were braving the rough seas on the east side of Guam in their sailing canoes. Pelagic fishing during the pre-contact period is not common on other Pacific islands outside the Marianas. However there is evidence of pre-contact fishing for mahimahi and marlin on either side of the Luzon Strait, which includes southern Taiwan and the northern Philippines.

For further reading

Amesbury, Judith R. “Pelagic Fishing in Prehistoric Guam, Mariana Islands.” Pelagic Fisheries Research Program Newsletter 13, no. 2 (2008): 4-8.

University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Pelagic Fisheries Research Program. “An Analysis of Archaeological and Historical Data on Fisheries for Pelagic Species in Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands.” By Judith R. Amesbury and Rosalind L. Hunter-Anderson. Mangilao: MARS, 2008.

US Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. Review of Archaeological and Historical Data Concerning Reef Fishing in the US Flag Islands of Micronesia: Guam and the Northern Marianas. By Judith R. Amesbury and Rosalind L. Hunter-Anderson. Final Report. Mangilao: MARS, 2003.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.