Lowest class, lowest caste

In the social organization of Chamorro/CHamoru society, individuals from the lowest class were known as manachang. In her study of early CHamoru culture, anthropologist Laura Thompson noted in the early Spanish mission accounts that the manachang were supposedly of smaller stature and had a darker complexion than the noble class matao. Based on this description, it has been speculated that the mangachang may have represented a distinct cultural group, and perhaps, were the original inhabitants of the Marianas until they were conquered by the more powerful chamorri. However, it seems more likely that the malnourished physical condition of the manachang as observed by the Spanish priests was due to a consistently poorer diet and continual exposure to the sun.

The mangachang class tended to live away from the coastlines, which were reserved for chamorri families. Manachang were also prohibited from entering or being near the homes of matao without permission. The social separation of manachang from the upper class was necessitated by their perceived uncleanliness. Indeed, the matao and acha’ot (of the higher caste chamorri) refused to use anything created or manufactured by manachang, except for sennit, cordage, certain kinds of mats, baskets and other woven articles. The upper classes also refused to eat any foods prepared by them except for rice, roots and a few other food items, lest they be tainted by the manachang.

Regulated tasks

The manachang also were banned from participating or acquiring skills in activities reserved for the upper class, including seafaring and ocean fishing. The manachang, however, did cultivate the soil and provided some food for the chamorri. The Spanish friar Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora in 1602 described the manachang as servants who farmed the land, and lived in the jungles and hills of the island. Though they were of lower status, Zamora asserts they were treated well by the principales or upper class CHamorus.

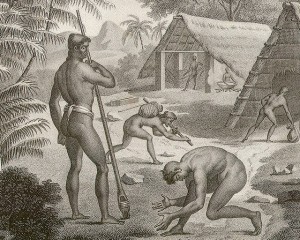

French researcher Louis Claude de Freycinet, who visited the Mariana Islands to collect scientific empirical data in the early 19th century, said the manachang not only cultivated field crops, but they also engaged in hunting. Other tasks relegated to the manachang were the construction of homes, canoe houses and other shed-like structures, and the cleaning of roads and paths, and carrying food items during warfare. Because the manachang could not fish in open water, they fished in rivers for eels, the only fish item they were allowed to eat. They also had to capture the animals by hand or with sticks, as they were not allowed to use hooks, nets or spears. They were not allowed to fish in the open ocean because it was believed by the higher caste that they would taint the water.

Manachang were also expected to be deferential in any encounter with matao. Bowing low to the ground as they approached, offering to carry heavy items for them or offering them gifts were all signs of respect a manachang individual could show to a matao. Sometimes in the effort to not hold his head erect a manachang could be bent so low to the ground it would seem as if the individual was on all fours. Indeed, a manachang did not even dare walk in front of people of superior social rank. Any lack of respect in this regard was considered a challenge, and justifiable by death of the manachang individual.

Perhaps the most restrictive aspect of social stratification was the prohibition of intermarriage or even sexual relations between matao and manachang. Freycinet explains, however, that although this prohibition existed, there were times when matao men had relations with manachang women. A matao man would go to great lengths to conceal his activities, or risk punishment by his family. To avoid direct punishment, he would renounce his social ranking and join another group as an acha’ot. This movement between social rankings within the chamorri caste indicates that matao or acha’ot were class statuses.

Although the chamorri class would eventually be replaced by the mannakhilo’, the manachang remained the lower of the social class. The poorest of these would be known in the new Spanish social colonial order as the mannakpåpa’.

For further reading

Blaz, Ben. Bisita Guam: A Special Place in the Sun. Fairfax: Evers Press, 1998.

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

–––. “The Ancient Chamorros of Guam.” In Guam History: Perspectives.Volume One. Edited by Lee D. Carter, William L. Wuerch, and Rosa Roberto Carter. Mangilao: Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1997.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

I Ma Gobetna-na Guam: Governing Guam Before and After the Wars. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1994.

Nelson, Evelyn Gibson, and Frederick J. Nelson. The Island of Guam: Description and History from a 1934 Perspective. Washington, DC: Ana Publications, 1992.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.

Russell, Scott. Tiempon I Manmofo’na: Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1998.

Spoehr, Alexander. Saipan: The Ethnology of a War-Devastated Island. 2nd ed. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2000.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.