Matao and Acha’ot

Table of Contents

Share This

Higher social class

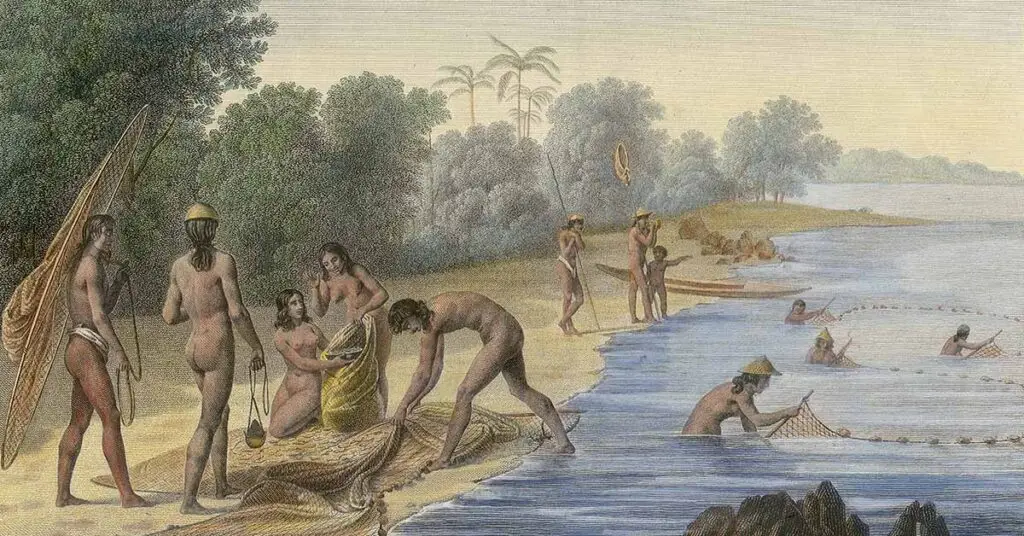

Early accounts of traditional CHamoru/Chamorro society describe at least two distinct social castes—the chamorri, or upper caste, and the manachang, or lower caste. The chamorri caste was further divided into the social rankings of matao and acha’ot. The matao were the nobles in CHamoru society, the highest-ranking individuals and leaders of clan and village groups. They were the wealthiest and the most privileged of the different social classes. They lived in settlements along the coastlines of the islands. Because of their exclusive access to the lagoon, reef and the open ocean, the matao were sailors, traders, warriors, fishermen, and canoe-builders.

Although early Spanish accounts do not mention a distinction within the chamorri caste, an account by Fr. Joseph Bonani, a German Jesuit living in Rota in 1719, specifically mentions the acha’ot class as separate from the matao. This is later affirmed by French explorer Louis de Freycinet in the 1819 account of his visit to the Mariana Islands. The acha’ot were ranked beneath the matao and are often referred to as assistants or helpers to the matao. They were artisans, craftsmen and healers. The makånas, or traditional healers and sorcerers, were from this class.

Many acha’ot individuals were related to matao, or were themselves once matao, but who had been demoted to acha’ot as punishment for serious offenses. A matao man, for example, who engaged in a forbidden relationship with a woman from the manachang caste could be banished from his village and reduced to an acha’ot. However, an acha’ot could regain or improve his social rank if he proved himself worthy in battle or by exceptional service to his community.

Leaders

The chamorri were also involved in village leadership. A council composed of high-caste males and females would meet to discuss and make decisions concerning village matters. All chamorri could attend these meetings, but only matao could participate, while acha’ot merely observed the proceedings.

Spanish friar Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora who jumped ship in 1602 and lived among the CHamoru people in Rota for seven months, used the Spanish terms principales for the upper class and criados or “mangachanes” for the lower class. According to Zamora the CHamorus living along the beaches in coastal villages were of higher social status than those living in inland villages. The criados or mangachanes, were more like servants to the principales, who treated them well by Zamora’s standards. In turn, the criados showed great respect to the principales, such as refusing to go near the houses or boats of the upper class without permission. The upper class was also treated more respectfully, given the first and best places during gatherings, and offered the best foods. Other historical accounts cite that the manachang were not allowed to even touch the ocean for fear that they would spoil the fishing.

Fr. Diego Luis de San Vitores, the Spanish Jesuit who set up the first Catholic mission and colonial government in the Marianas, also described the two social castes. He noted the deferential treatment the manachang had for the upper class chamorri, as well as the elitist character of the chamorri who insisted that the Christian sacrament of baptism be limited to the nobility as a privileged ritual, much to San Vitores’ chagrin. Freycinet’s 1819 account mentions the acha’ot as a separate social class from the matao. Frecyinet also describes the character of the nobles as “honorable” and “motivated by a love of truth.” In contrast the manachang were “audacious liars, base, inhospitable and without faith.” However, Freycinet was unimpressed by the perceived vanity and pride of the upper class.

Controlled resources

The upper class matao had exclusive privileges over ocean resources, and therefore, could navigate and engage in open-sea fishing. In addition, the matao were the only ones allowed to engage in trade with other islanders. According to Freycinet, each matao had control over a certain stretch of water which he could not go beyond without the permission of neighboring chiefs. Manachang could access the ocean for fishing only with the expressed permission of the matao. An acha’ot was sometimes granted access to the ocean for fishing or land for cultivating as rewards for good behavior. The manachangs, though, according to Freycinet, had to fend for themselves, working the land to provide food for themselves and their matao masters.

Funerary rites

Perhaps one of the most distinctive features surrounding social class was the difference in burial treatment of the dead. Being an upper class CHamoru afforded certain privileges and ceremony not presented to those of lower status. Zamora’s companion Sancho described the custom for “leading citizens” in terms of burial practices:

What they ordinarily do with their dead, however, is to cut the hair and wrap the body in a new mat, which serves as a shroud. Two of the deceased’s female relatives arrive, who are among the oldest women of the village and lay pieces of tree bark or of painted paper on top of the body. Then they begin singing and crying, simultaneously asking so-and-so, calling him by name—why have you forsaken us? Why have you departed from our sight? Why have you deserted the women who love you so?…More than two hours are spent in this manner, repeating these and other things. Amidst many tears, his relatives embrace him and carry him away…The dead are buried in front of the most prestigious relatives’ house.

This occurs after the already-decomposing body has been placed on a scaffolding of palms and trees.

In addition, Freycinet describes that after a noble has died, the CHamorus would “tear up their fruit trees, burn down their own houses, smash their canoes, rip up the sails and hang the broken and torn fragments in front of their own dwellings.” Items specific to the individual’s skills, such as paddles or spears would be laid on the body. This would be performed before the individual was buried in the home of the highest ranking family member to ensure closeness to the deceased spirit’s family.

Demotion

Another distinctive feature of CHamoru society was the fluid movement of individuals between the matao and acha’ot classes because of social or cultural infractions. As mentioned earlier, an individual matao could be demoted to the rank of acha’ot as punishment. If an acha’ot was expelled from his own group, he would seek out a matao to be placed under his service, otherwise the acha’ot and his family could not settle anywhere and be “forced to wander.” The wife and children of a punished acha’ot were also demoted until the individual was forgiven or completed his sentence. If an acha’ot died in exile, his wife and children remained acha’ot.

Matao who had been punished, depending upon the offense, could have their punishments revoked through gifts of atonement from their wives and relations. Some matao who had proven themselves as strong and self-sustaining might escape ever being demoted to acha’ot for wrongdoing, although if the offense was grave enough, care would be taken to ensure the matao would be subject to the common law, if even in a roundabout way.

Although the matao and acha’ot were the highest-ranking individuals in traditional society, with the arrival of the Spanish and the establishment of a new social order, the chamorri class would eventually be replaced by another social class. No longer would matrilineal affinities necessarily determine social ranking, but rather, the ability of individuals to link themselves with the new colonial administrators and church officials economically, politically and socially. This new emergent class would be known as the mannakhilo’.

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Kinship Organization. Agat: L. Joseph Press, 1984.

–––. “The Ancient Chamorros of Guam.” In Guam History: Perspectives. Volume One. Edited by Lee D. Carter, William L. Wuerch, and Rosa Roberto Carter. Mangilao: Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1997.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

I Ma Gobetna-na Guam: Governing Guam Before and After the Wars. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1994.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1995.

Russell, Scott. Tiempon I Manmofo’na: Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1998.

Spoehr, Alexander. Saipan: The Ethnology of a War-Devastated Island. 2nd ed. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2000.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.