Women’s authority

Women today continue to maintain positions of authority in Chamorro/CHamoru society, both at home, in Chamorro families, and in professional careers whether they are Chamorro or of other ethnic backgrounds.

Chamorro women maintaining a central role in decision making is a traditional value that has carried on throughout the centuries despite numerous changes and challenges such as the Christianization of Chamorros in the latter part of the 17th century, and American hegemony beginning in the 20th century. Women were able to maintain their authoritative roles in the face of patriarchal values because of mothers’ traditional custodial roles. Women are responsible for child-rearing, finances, and family responsibilities.

Matrilineal society

Chamorro women in leadership roles is documented in early European writings about ancient Chamorro lives and cultural practices. From what is known of ancient Guam, especially of practices of the matao (the upper caste) it was a matrilineal society, with people tracing kinship through mothers’ family lines. Children belonged to mothers’ clans. The allocation of resources, such as land, were passed on to generations through the mother’s side of the family. Chamorros were able to find a societal equilibrium as both men and women – the eldest brother and sister – were co-equal guardians and administrators of clans and their resources.

The Chamorro creation myth, Puntan yan Fu’una, with the brother and sister holding equally strong roles in creating the world and humanity, illustrates how women’s roles have been perceived from ancient times by Chamorros.

While men served a more visible role in policy decisions, women also had great influence as no major decisions were made without their input and agreement. Village councils, made up of the highest ranking males and females of the villages, created public policy through consensus, or todu manatungo.

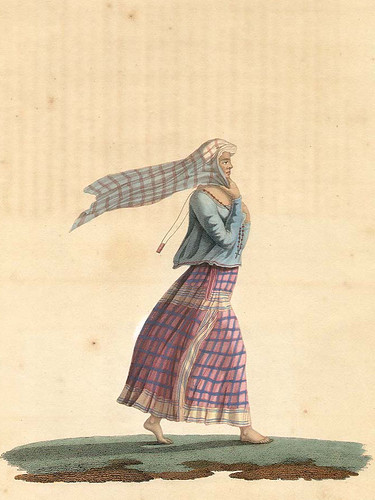

In ancient Chamorro society men were responsible for tool making, canoe building and navigation and off-shore fishing. Women were in charge of the household, weaving, food preparation, pottery making and inshore fishing. Additionally, women would juggle household responsibilities and duties while working alongside men in performing other tasks to ensure the well-being of the community such as fishing and agriculture.

Snippets of life provided in historical texts describe women as held in high regard by virtue of motherhood and as heads of households. Guam and Its People, a study of Guam by anthropologist Laura Thompson, cites observations made by 17th century Catholic missionary Father Diego Luis de San Vitores.

Among the ancient Chamorros, women held a relatively high position. ‘In each family the head is the father or elder relative, but with limited influence,’ wrote Sanvitores. … In the home it is the woman who rules, and her husband does not dare give an order contrary to her wishes. Nor punish the children for she will turn on him and beat him.

Christian indoctrination and changes

Spanish colonization of the Mariana Islands was largely the result of the evangelical efforts of San Vitores. As the Spanish tried to Christianize Chamorros, their efforts affected Chamorro society and culture.

Under this colonial rule Chamorro’s matrilineal society adapted to become a bilateral one over time. Many Chamorro men lost their lives in revolts against Spanish rule. The Chamorro population was doubly impacted as many Chamorros died from introduced Western diseases to which they had no immunity. Then through the reducciones, a forced resettlement of Chamorros from throughout the Marianas archipelago, Chamorros were displaced from their clan lands and cultural practices. Pueblos (villages) were established on Guam with the Catholic church becoming the focal point in Chamorro lives.

Lives revolved around religious activity in these new villages. People attended Mass daily, recited rosaries three times throughout the course of a day and children attended Catholic schools. Fathers were defined by the Catholic Church as the head of household. Men would go to their låncho (ranch), however, to farm usually for days at a time leaving the mothers at home with the children. This dynamic allowed Chamorro women to maintain their roles as heads of households despite men being legally recognized as such because mothers were still responsible for educating their children in familial, social and religious activities. Mothers taught their children the Chamorro language and cultural values.

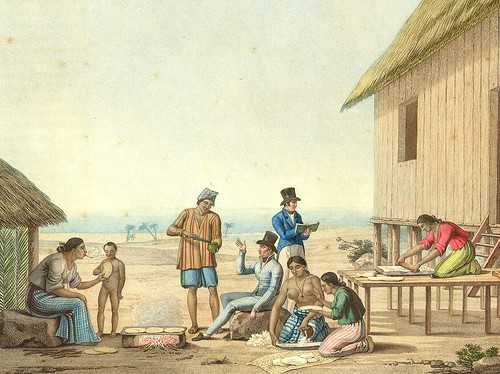

After more than a century of Spanish rule, French explorer Louis Claude de Freycinet led an expedition in the Pacific that would eventually lead him to Guam in 1819 to compile scientific and ethnographic data. During his three month stay he observed and documented the role of Chamorro women.

At home, they were absolute mistresses and had the command of everything: nothing was done without first obtaining their opinion and consent. And even today, though time has filed away the outlines of most ancient customs and left barely a few faint traces, that traditional deference of the Mariana Islanders to their female companions has lost nothing of its strength. In our French eyes, indeed, that deference seemed almost excessive, so accustomed are we to our views on relations between the two sexes.

20th century patriarchy

American rule began when Guam was ceded to the United States as a spoils of war with Spain in 1898. Then came further social changes that threatened to lessen women’s roles in society. In Daughters of the Island, author Laura T. Souder discusses how American authorities legally mandated patriarchy.

Matrilineage was outlawed. The Spanish custom of allowing children to take their mother’s name had predisposed Spanish officials to accept this preference among early Chamorros. American naval officers on the other hand took exception to this practice. Hence, Chamorros were forced to abide by patriarchal notions of descent. Executive Order No. 308 promulgated by the Naval Government on April 3, 1919 declared that a married woman should bear the surname and follow the nationality of her husband: and further that children should bear the surname of the father. In addition, the people of Guam were exhorted to Americanize their children’s names.

Contemporary society

Despite the challenges maternal authority has faced throughout the centuries, the ancient practices of the Chamorro social system have prevailed allowing remnants of matrilineal practices to remain. Chamorros outwardly accepted and adapted to the changes while maintaining the emphasis of the importance of women in society.

In 2008, Guam had its first female legislative speaker when Judith T. Won Pat, a Chamorro woman, was elected by her colleagues of I Mina Trenta na Liheslaturan Guahan/the 30th Guam Legislature. Five years earlier, Guam’s electorate selected its first female delegate to the US Congress, Madeleine Z. Bordallo. She also previously served as a Guam senator and first lady (married to former Governor Ricardo J. Bordallo). More than a decade prior to the seating of Won Pat and Bordallo, in 1990, one-third of the 21 legislative seats were held by women, and in the 30th Guam Legislature, again, nearly one-third of the legislative seats are occupied by women.

In 2018 the people of Guam elected its first woman governor, Lourdes A. Leon Guerrero.

These are just some of the more current instances of women in public office holding positions of status. Prior to this, in the realm of public education, women have held positions of authority including that of local education department superintendent. In the past, and still applicable today, women have been at the helm at the University of Guam as university president, vice presidents, deans and regents.

For further reading:

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

Herman, RDK. “Guam: Inarajan – Native Place: Village.” Pacific Worlds, 2003.

Souder, Laura Marie Torres. “Unveiling Herstory: Chamorro Women in Historical Perspective.” In Pacific History: Papers from the 8th Pacific History Association Conference. Edited by Donald H. Rubinstein. Mangilao: Micronesian Areas Research Center, University of Guam, 1992.

Souder-Jaffery, Laura Marie Torres. Daughters of the Island: Contemporary Women Organizers of Guam. MARC Monograph Series 1. Mangilao: Micronesian Areas Research Center, University of Guam, 1987.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.