A ministerial role

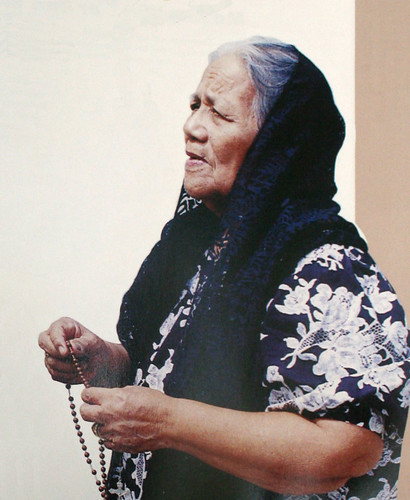

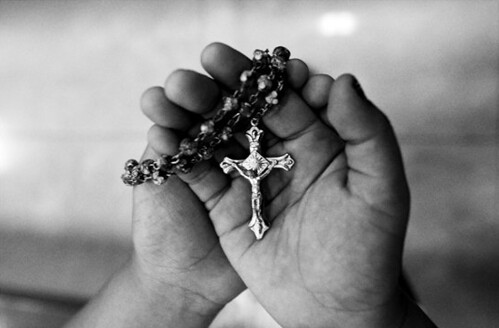

In the Mariana Islands, the techa is the traditional prayer leader who directs and recites the prayers and hymns for various religious activities within the Catholic Church, including rosaries or lisayo, novenas or nobena, and other devotions and special occasions.

The word techa comes from the Chamorro/CHamoru verb tucha, which is translated as “to recite out loud,” or “to lead or start a prayer.” To be recognized as a techa one must demonstrate the ability and confidence to direct others through the different prayer rituals as well as be accepted officially by the parish pastor and faith community. The techa is not an ordained position within the Catholic Church, but rather, is seen as “an extension of the ministerial role of the parish priest or pastor”. Like a priest, the techa is committed to a life of service and a promise to lead prayers upon request.

Although most techas are elderly women, the role is not limited to them, and indeed, there are a small number of men and young people who are techas. But the majority of techas has been and are elderly women, and because of this, it is largely perceived as a “woman’s role.” In addition, there are families of techas, whereby younger female relatives — usually eldest daughters or interested individuals — are trained to become prayer leaders through practice and encouragement.

Musical interchange

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the more traditional image of a techa is the style of prayerful recitation, which is often characterized by high-pitched nasal, virtually monotonous vocalization, and a fairly rapid but steady pace that the congregation must follow in order to respond appropriately. What is heard is an almost musical interchange between the techa and the congregation as she solemnly leads the prayers phrase by phrase, and the people reply in turn. A skilled techa is able to keep this rhythm while successfully directing the others through a meaningful experience of prayer.

A techa generally carries out her role without set fees, but when she is called upon to lead, she is usually compensated for her services either with gifts of food or money. The amount is often left to the discretion of the family she is helping, but presumably it is based on the level of esteem the family may have for the particular techa, and the number of days the family has availed the techa of her services.

The money for the prayer leader is represented as a portion of the chenchule’ or ika’, which are reciprocal gifts of money, support or assistance that are given in the event of a death or other occasion to defray expenses. Some prayer leaders choose to donate a portion or all of the money she receives back to the parish church. A highly regarded techa may receive continued accolades and gifts of prayers and thanks from the community when she dies, in honor of her prior service to them as a prayer leader.

Likened to traditional chanting

The origin of the techa has never been extensively documented. However, it is generally accepted as a role that extends at least as far back as the Spanish occupation of the island in 1668, perhaps even further. Indeed, the characteristic monotonous nasal style by which a techa recites prayers, especially in the repetition of phrases in the rosary and the litanies, has been likened to the traditional chanting and weeping described in ancient CHamoru funeral practices.

Perhaps it can never be known what is the true origin for the role of the techa, but it is a role that continues in CHamoru culture because it effectively fulfills the needs of the Catholic faith community.

For further reading

Chamorro Heritage, A Sense of Place: Guidelines, Procedures and Recommendations For Authenticating Chamorro Heritage. The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Department of Chamorro Affairs, Research, Publication and Training Division, 2003.

Iyechad, Lilli Perez. An Historical Perspective of Helping Practices Associated with Birth, Marriage and Death Among Chamorros in Guam. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2001.

Souder-Jaffery, Laura Marie Torres. Daughters of the Island: Contemporary Chamorro Women Organizers on Guam. 2nd edition. MARC Monograph Series No. 1. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1992.

Spoehr, Alexander. Saipan: The Ethnology of a War-Devastated Island. 2nd ed. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2000.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.