Map

Flag

Quick facts

Official Name: Tokelau

Indigenous Peoples: Tokelauan, in the Polynesian family

Official Languages: Tokelauan, Samoan, English and Tuvaluan

Political Status: Non-self-governing territory of New Zealand

Largest City: Fakaofo

Population: 1,411 (2011 est)

Greeting: Mâlô nî or Tâlofa

History and geography

Tokelau consists of three tropical coral atolls (from the northwest, Atafu, Nukunonu and Fakaofo), as well as Swains Island, which is governed as part of American Samoa, with a combined land area of 4 sq mi. Its capital rotates yearly between the three atolls. Tokelau lies north of the Samoan Islands, Swains Island being the nearest, east of Tuvalu, south of the Phoenix Islands, southwest of the more distant Line Islands, and northwest of the Cook Islands.

The atolls of Tokelau were settled about 1,000 years ago. The three atolls function largely independently while maintaining social and linguistic cohesion. Tokelauan society was governed by chiefly clans, and there were occasional inter-atoll skirmishes and wars as well as intermarriage. Fakaofo, the “chiefly island,” held some dominance over Atafu and Nukunonu after the dispersal of Atafu. Life on the atolls was subsistence-based, with reliance on fish and coconut.

Commodore John Byron arrived in Atafu in 1765 and named it “Duke of York’s Island.” Landing parties onshore reported that there were no signs of current or previous inhabitants. Captain Edward Edwards, knowing of Byron’s discovery, visited Atafu in 1791 and found no permanent inhabitants, but houses contained canoes and fishing gear, suggesting the island was used as a temporary residence by fishing parties at the time.

Contact with Europeans led to some significant changes in Tokelauan society. Trading ships brought new foods, cloth and materials, and new ways of doing things. In the 1850s, missionaries from the Roman Catholic Church and the London Missionary Society, with the assistance of Tokelauans who had been exposed to religious activities in Samoa, introduced Christianity. Currently, most people on Atafu are Congregational Christians and most on Nukunonu are Catholic. In Fakaofo, most are Congregational Christians, and most of the remainder are Catholic.

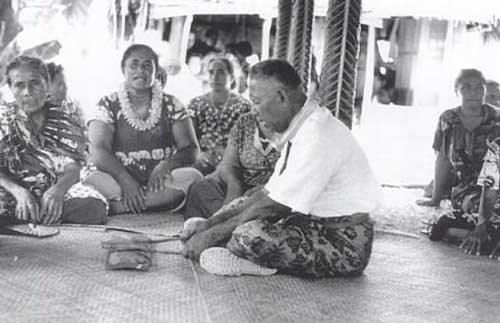

In the 1860s, Peruvian slave ships visited the three atolls and forcibly removed almost all able-bodied men (253) to work as laborers in Peru. The men died by the dozens of dysentery and smallpox, and very few ever returned to Tokelau. The impact of the slave ships was devastating, and led to major changes in governance. With the loss of chiefs and able-bodied men, Tokelau moved to a system of governance based on the Taupulega, or Councils of Elders. On each atoll, individual families were represented on the Taupulega (though the method of selection of family representatives differed among atolls). Village governance today is squarely the domain of the Taupulega.

Tokelau became a British protectorate in 1877, a status that was formalized in 1889. The British government annexed the group (which had been renamed the Union Islands) in 1916, and included Tokelau within the boundaries of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony (Kiribati and Tuvalu). In 1926, Great Britain passed administration of Tokelau to New Zealand. There has never been a residential administrative presence on Tokelau, and, therefore, administration has impinged very little on everyday life on the atolls. Formal sovereignty was transferred to New Zealand with the enactment of the Tokelau Act of 1948. From that time, many Tokelauans migrated to New Zealand. Although Tokelau was declared to be part of New Zealand from 1 January 1949, it has a distinctive culture and its own political, legal, social, judicial and economic systems.

Over the past three decades Tokelau has moved progressively toward its current advanced level of political self-reliance. In November 2004, Tokelau and New Zealand took steps to formulate a treaty that would establish Tokelau as a “self-governing state in free association with New Zealand,” rather than a non-self-governing territory. Although one time many Tokelauans advocated for independence, with the threat of climate change and rising sea levels, most people want to maintain ties with New Zealand. Tokelau has its own unique political institutions, including a national legislative body and Executive Council. It runs its own judicial system and public services. It has its own shipping and telecommunications systems. It has full control over its budget. It plays an active role in regional affairs and is a member of a number of regional and international bodies.

Tokelau’s economy consists of subsistence agriculture and fishing. Land tenure is based on kinship lines and land reserved for communal use. In the 1980s New Zealand established a 200-mile (320-km) exclusive economic zone, and a fisheries training program was started by the South Pacific Commission. Tauanave trees are specially grown on selected islets for canoes, houses, and other domestic needs.

Solar power installations on each of the three atolls provide enough electricity to meet nearly all of Tokelau’s energy needs. The New Zealand dollar is the main currency used, although the Samoan tala is also sometimes used. Tokelau imports goods from New Zealand. Food, building materials, and fuels are the main imports; a small amount of copra is exported. The islands have neither roads nor vehicles. Tokelau does not have a port. Ships must anchor off the reef.

Arts and culture

The people of Tokelau are Polynesians in language and culture. The Tokelau language is a member of the Samoic subgroup of Polynesian languages and closely related to the language spoken in Tuvalu. Until recently, most people were bilingual in Tokelauan and Samoan because of their introduction to Christianity via the Samoan translation of the Holy Bible.

The guiding principal of Tokelau cultural values is maopoopo which means, “a unity of a common purpose that encompasses both body and spirit.” Maopopo can be seen in the communal activities Tokelauans participate in with each other, such as fishing expeditions, construction, sports competitions, and music and dance. The inati system is another example of the emphasis of community, cooperation and sharing among the Tokelauans. Village men go together on a fishing expedition, and when they return, they ritually divide and share their catch with all the clans on the island.

Traditional villages are located on the leeward islet of each atoll. Homes which until recently used to be constructed of thatch, are rectangular in shape; cooking areas are located in the back of the village where the wind can blow smoke from fires away from residences.

Early European accounts describe the presence of ocean-going double-hulled sailing canoes and various types of fishing equipment and watertight boxes called tuluma as common sights in the village. Men and women had separate but complementary roles, with usually women processing food and raising children, and men fishing and harvesting. Land was owned communally and land rights inherited from both parents. Villages were ruled by a council of male elders or heads of recognized kin groups that made and enforced local regulations and made all major decisions for the village.

Not much is known about the religion of Tokelau before the introduction of Christianity. There are accounts of Tui Tokelau as a preeminent, which was represented by a huge mat-wrapped pillar in front of his shrine in Fakaofo. Annual rites were carried out to ask for fertility and success. It is also known that kin groups had their own gods and spirits associated with them.

Tokelauans continue to nurture traditional skills such as wood carving and mat making. Performance arts are well-developed and express much creativity. Poetry, music, rhythms and dance are combined in old and new group compositions, with sometimes informal competitions taking place between dance groups. There is also a tradition of comic performance and clowning, usually by older women.