When the SMS Cormoran II arrived in Guam in December 1914, among the hundreds of crew members were individuals who worked on the vessel but were not German. Twenty-nine men originally from German New Guinea in the South Pacific and four Chinese men from Tsingtao stayed on Guam along with their German counterparts for the duration of the Cormoran’s internment at Apra Harbor.

The four Chinese worked as laundry men aboard the ship and had been recruited at the German colony at Tsingtao. Their names were:

1. Lan Jon Scheng

2. Lan Jon Tschang

3. Tschan Wain King

4. Wan King Chie

After the scuttling of the Cormoran in April 1917, the German sailors were taken as prisoners of war. The Chinese men, however, were rescued from the Cormoran and released. According to Herbert Ward, author of The Flight of the Cormoran, the men were “temporarily employed as house servants on Guam.” Charles Burdick, author of The Frustrated Raider, wrote that the men chose to stay on Guam and successfully opened their own laundry. However, not much else is known or recorded of the Chinese crew members, whether they remained or decided to move elsewhere as they do not appear to have left any descendants on Guam. It is likely the men actually made their way back to China on a passing ship; however, it is not clear when they could have left Guam.

There is also some discrepancy regarding the names and number of the New Guinean crew members and when they actually became a part of the Cormoran crew. According to Ward, there were 28 New Guinean crew members, while Burdick states there were 29. Ward also wrote that all of the New Guinean crew members were part of the original Cormoran crew in Tsingtao. In contrast, Burdick wrote that only 11 New Guinea crew members joined the Cormoran crew in Tsingtao, along with the laundrymen, to carry out miscellaneous jobs aboard ship. He does not make clear when or how the other 18 members came to work on the ship. Perhaps the rest of the Melanesian islanders came on board in Yap after the scuttling of the German survey ship, the SMS Planet, or perhaps while the Cormoran was making its way through German New Guinea before heading back to Micronesia.

In any case, Ward’s book also only provides the names of 24 Melanesian men:

1. Aves

2. Baseh

3. Bigi

4. Bumarum

5. Danunbure

6. Divu

7. Gewei

8. Kap

9. Kambine

10. Kamembur

11. Kanagui

12. Kara

13. Lellai

14. Lublub

15. Möwa

16. Nava

17. Papu

18. Popian

19. Reqallei

20. Telania

21. Tamgul

22. Teiu

23. Tjimel

24. Wowore

However, an official memorandum by Acting Secretary of State Frank L. Polk documenting the transfer of the men off Guam back to New Guinea in 1919 mentions there were 28 New Guinea men, and adds the names Mumburum, Bio, Boi and Niu to the list. And finally, in one of the annual newsletters of the Cormoran reunions in Germany there is mention of another young New Guinean on neither Polk’s or Ward’s lists named Moritz, who had gotten into trouble with one of the young women in Lamotrek for which he was duly punished.

The men from New Guinea officially were listed as “galley attendants” and did much of the labor as part of the Cormoran crew. Five of them also were sent ahead to Guam accompanying Lt. Hubert Frank while Captain Adalbert Zuckschwerdt hid the Cormoran at Lamotrek atoll.

When the Cormoran was scuttled, the New Guinea crew members were rescued and released. They, like the Chinese, were not taken to the US mainland as prisoners of war and instead, remained on Guam for a time and were hired as laborers for land clearing projects.

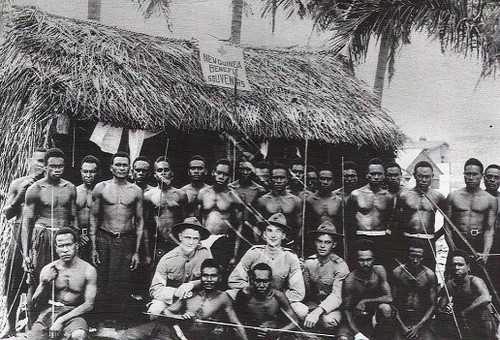

No doubt the presence of the Melanesians left quite an impression on the local residents. Ward described the reaction of the locals to the New Guinea crew members as follows:

They [the New Guinea crew members] were a source of great amusement (and even some slight apprehension) to the residents of Guam. These muscular Melanesians were curious sights in their uniforms, consisting of red ankle length skirts, secured at the waist by a rolled piece of cloth, or an occasional German Navy belt and brass buckles. It was a popular belief that they had all been cannibals at one time, and one had supposedly confessed to eating part of his own grandmother (which, true of not, made a good story and got a satisfactory reaction from the listener.) Guam’s Christian inhabitants could scarcely imaging [sic] such barbaric practices, and were properly appalled.

A camp was set up in [the village of] Piti and promptly dubbed ‘Canninbal Town.’ Another outlying camp was established at the quartermaster’s construction camp at Sumay, where working parties were put to clearing land on the Naval reservation, assisting in construction, waterfront activities and road building. The men were paid good wages for their work, well treated and apparently were contented. Food was somewhat of a problem, as they did not seem to fare too well on Navy rations. Eventually their food rations had to be reduced, as they would gorge themselves at mealtime and then go to sleep. They could scarcely be aroused again for work.

The men from New Guinea also participated in the first annual Guam Industrial Fair, which, in 1918, was held over the Fourth of July Weekend. Ward describes, “The New Guinea men, in their native costumes, performed at the fair with exhibitions of spear hurling and dancing. Their pierced earlobes and nostrils containing various ornaments added generously to their fierce appearance, and the accuracy of their spear throwing commanded no little respect.”

One of the New Guinean crew members, Bumarum, reportedly “married” a CHamoru woman. However, he became ill shortly afterward, and passed away in 1918. The other New Guineans believed Bumarum had broken one of their cultural taboos against marriage to foreigners which led to his death. Also against their culture, Bumarum was buried alongside the other Cormoran crew members at the US Naval Cemetery in Hagåtña, with full Christian ceremony. It is not known if Bumarum had any children on Guam, or if any of the other New Guinea men left any descendants behind among the local population.

In January 1918, the British government took over the former German New Guinea and all the responsibility for the New Guinea men. By January 1919, the men were placed on the Japanese schooner Dai Ichi Tora Maru and left Guam to return to their homeland.

For Further Reading

Burdick, Charles. The Frustrated Raider. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1979.

Ward, Herbert T. The Flight of the Cormoran. New York: Vantage Press, 1970.