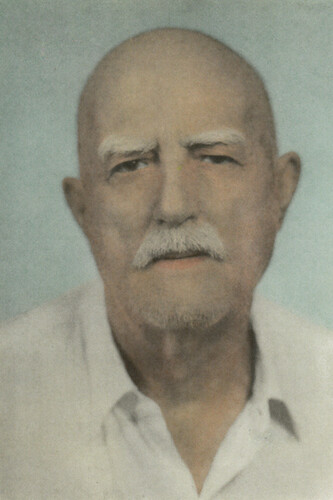

Businessman, rancher, patriarch

Don Pascual Artero y Saez (1875 – 1956) was a prominent Spanish businessman, rancher and patriarch of the Artero family in Guam. Born in Mojácar, he served with the Spanish military in the Western Pacific, married on Yap and settled in Guam at the turn of the 20th century.

With his young family he created two large ranches with pasture lands for cattle in Upi and Toguag (Dededo and Yigo) and provided meat to the island. He also ran a saw mill that provided lumber and wood. Artero built up his wealth during the early Naval administration (1898-1941) of the island, only to lose most of it during the Japanese occupation of Guam in World War II.

Known as a prayerful, devout Catholic, a generous individual and a man of character, Artero left a legacy for his many descendants of business savvy, a hardworking attitude, a willingness to dream big and a loyalty and devotion to the island and its people.

Early Life

Pascual Artero was born on 28 May 1875 in the poor village of Mojácar in the province of Almería of Southern Spain. Although he never knew his father who had died before Artero was born, he was fond of his stepfather whom his mother had married in September 1876 after having lost her first husband. Artero is not known to have any siblings, but did have numerous close family relations. Although Artero had never gone to school, his stepfather was a literate man and was able to teach him the basics of reading and writing at home.

In his autobiography, Artero described himself as a robust and healthy child, mischievous, daring and determined. At one time, he had a serious accident while taking a mule to graze when the animal slipped and fell on him. His parents believed he would not survive his injuries and dressed him in funeral clothes, but the boy did survive. When he recovered he helped his mother with their farm while his stepfather left Spain to find temporary work in Algeria.

The land in Mojácar is dry and difficult to cultivate. At the tender age 10, Artero persuaded his mother to let him leave their farm to find work in Africa. He found a job clearing land for farming and also as a water boy earning only half of what the men in his work group received. From 1886 to 1888, he would leave home during the planting season to find work in Africa and Iran, clearing land and cultivating grapes, all the while developing his skills in planting, harvesting and reaping.

Artero also wanted to learn how to read and write better, so he offered a goat to a friend to teach him. While he was away from home, Artero would write letters to his stepfather, although he was never sure his stepfather could understand his writing. He would send home most of his wages to help his family and save the rest. When Artero returned home as a young man, he described himself as a “good wheat thrasher” and believed he would continue his life as a peasant farmer in Mojácar.

First love and military service

Artero claimed his first love was a young peasant girl named Ursula, a distant relative in Mojácar, whose mother closely supervised his visits with her daughter. However, the young man entered the military and in May 1895 he was sent to Cartagena to begin his military service. Artero caught on to things quickly and soon was named a provisional corporal. Later he was sent to San Fernando in Cádiz. Eventually he was assigned to the Naval infantry and upon reaching the rank of corporal, he was sent again to Cartagena. After a year he was allowed to return home. Dressed in his Naval uniform he was unrecognized by the townspeople, but once revealed, Artero’s family welcomed him warmly–he even was given more leeway to visit with his girlfriend Ursula.

Within one week, however, an insurrection broke out in the Philippines. Artero received orders to go to San Fernando to join the troops being sent to the Philippines to quash the revolt. Because of all the stops and rough seas, however, Artero did not arrive on time to leave with his group. Instead, he was assigned to Ramos Company, which handled military personnel returning from Cuba. Artero was made a quartermaster and placed in charge of the cooks.

In February 1898, he finally was sent to the Philippines on the transport Covadonga, but by the time he arrived in March, the Spanish troops were already pulling back as most of the fighting ended. He was sent to guard a convent in Bacoor, was promoted to sergeant and then transferred to Cavite.

Yap and Marriage

In July 1898 at the height of the Spanish-American War, Artero received orders to transfer to Yap for a three-year assignment. In Yap there was a prison for political exiles, mostly Filipinos, and Artero was placed in charge of the barracks. Life was slow for the young sergeant and he and the other soldiers would entertain themselves with cock-fighting and gambling while helping maintain order among the island’s villages.

It was in Yap that Artero met his future wife, a Spanish woman named Asuncion Martinez Cruz. Cruz was the daughter of a Spanish captain of the company in charge of munitions in Hagåtña. She had left Guam for Yap with her four sisters–Dolores, Milagros, Trinidad and Teresa–and their brother Francisco. Dolores and Francisco assisted in domestic chores, while Asuncion, Milagros, Trinidad and Teresa taught at a school set up by Doña Bartola Garrido. Garrido was a CHamoru woman who had openly defied the German claim to Yap by raising the Spanish flag. She started the first CHamoru community in Yap and invited Cruz and her sisters to teach the young people there.

Artero was smitten, though he had no intentions at the time of seriously courting Cruz for marriage. Nevertheless, the more he saw of her the more attracted he became to her integrity and sincerity. It was around this time that he received a letter from Ursula back in Spain telling him that if he did not return soon she would marry someone else. This letter broke his heart, but it gave him the opening he needed to give his heart to Cruz. He wrote to Spain asking the authorities to send his birth certificate to Yap so he could marry Cruz, but Cruz and her sisters decided to return to Guam.

Traveling by way of Japan, the trip took several months. By the time they arrived, the Spanish-American War had ended and Spain had sold the Caroline Islands to Germany. Artero, though, had remained in Yap and asked Cruz to return so they could marry. Accepting his proposal, Cruz boarded the schooner Esmeralda and the couple married on 6 December 1899. However, with the change in administration, Artero soon was forced to move. With an invitation from the Cruz family and a letter of recommendation from the Capuchin missionary from Yap, Artero and his bride sailed back to Guam on the Esmeralda in 1901. The couple would have seven children in the course of their marriage: Jesus, Antonio, Isabel, Maria, Consuelo, Pascual and Jose.

Building a life in Guam

Artero remained in Guam for the rest of his life and took to farming, the trade he learned as a boy, almost immediately upon his arrival. He began by sowing seeds and repairing an abandoned house for him and his wife to live. He grew sweet potatoes and eventually sugar cane, too, but looked for other opportunities to earn more money to support his family.

He began working for a Spanish captain named Pedro Duarte who had married a CHamoru woman a few years earlier. Duarte later recommended Artero to an American engineer as a day laborer to help build roads. Eventually, the engineer hired Artero to also help with a project to create the first complete map of the entire island. The map took three or four years to complete—the engineer would survey the land and Artero would place the flags to mark different locations.

The job did not pay much but it paid more than other jobs for residents in Guam. While measurements for the map were calculated, Artero continued the work of constructing roads, while also directing groups of men to build towers, blow up mountains and clear passages.

Around this time the Winster Commercial Company bought land in Upi (now Andersen Air Force Base) with the intention of planting 200,000 coconut trees. Artero worked for the Winster Company planting coconuts when his first son, Jesus, was born. He also worked with another Spanish rancher, Baltazar Bordallo, who owned pastures and livestock, helping him oversee the herdsmen. Bordallo paid Artero with one calf for every four born.

Artero sought other business opportunities. For two years, he secured a contract with the Naval government to collect garbage for the island. He was earning $30 to $40 a day before his contract ended. Artero later got a contract to construct a dam to increase the water supply for the island. He also had acquired enough cattle to hire young boys to help care for them.

When the Winster Company was unable to make use of the land in Upi they sold their assets. US Naval Lieutenant Commander Eugene L. Bisset, better known by Guam residents as “Captain Bisset,” arrived in Guam from the Philippines and became interested in buying the Upi property. Bisset approached Artero—who had marked off the property while he was an employee of the company—to show him the land. In 1904, Bisset purchased a 4,300 acre plantation in Upi for $5,700, and also bought a large house in Hagåtña, and the company’s warehouse in Piti.

He also acquired houses at Adelup (which at the time was called Pinta del Diablo, or Devil’s Point). Bisset hired Artero as administrator of all his properties and paid him $300 a month for Artero and his workers. In addition to his pay, Artero also made money raising his animals. By 1918 he and Bisset were selling cows to the government.

Surviving World War I and the Flu Epidemic of 1918, Artero continued building up his herd of livestock. The Governor of Guam arranged for Artero and businessman Pedro Martinez to regularly supply meat to the government. Martinez owned and operated the island’s ice plant in Hagåtña. He would send ice to Artero who operated the meat market. Using the ice, Artero opened up the first cold storage unit to preserve the meat he sold. Later, he was able to order the first refrigerators from the mainland to use in his butcher shop. As an administrator to Bisset’s properties, Artero also ran the meat business successfully until the Japanese invasion of Guam during World War II.

Bisset retired from military service in 1916 as a US Naval Commander, but was recalled into service in World War I. He continued his relationship with Artero on business as well as personal matters. Bisset wanted his properties in Guam to be passed on to his daughter, Eugenia, who was living in the Philippines. Bisset and Artero agreed that a marriage between Eugenia and Artero’s son, Jesus, would be arranged. Jesus left for Manila where he and Eugenia married and settled in Guam. The union between Eugenia Bisset and Jesus C. Artero produced 11 children: Pascual, Eugenio Jesus, Pedro, Eugenio Pascual, Bernardo, Maria, Jose, Fernando, Teresita, Ines and Josefina.

In 1938, Bisset gave his daughter, Eugenia, half of the Upi property and proposed that Artero buy the other half. However, foreigners were not allowed to own land in Guam, so Artero hired an attorney to put the land under the name of “Jesus, et.al.” Pascual Artero eventually acquired other properties to pasture his cattle and by the time he was 66 years old, the Arteros were then the largest land holder in Guam.

Because of his distinguished character, Artero was often referred to as “Don Pascual” or “Maestro,” or “Master,” as titles of respect. He was well known among the Americans, too, and was frequently sought out to provide information about the land and life in Guam.

By the late 1920s, Asuncion Artero had passed away. Don Pascual Artero married a second time to his sister-in-law, Teresa Martinez Cruz, whom he had also first met in Yap while stationed there. Teresa had never married and had no children. The couple endured the ravages and uncertainties of World War II together, and Teresa accompanied him on his final trip to Spain. She died on 25 September 1950.

World War II

By the time of the Japanese Occupation in 1941, Artero was to lose much of what he had worked the past four decades to acquire for his family. The invasion by Japanese forces on 8 December 1941 marked a turning point in Artero’s life. He had been attending Mass at the Agana Cathedral as the island celebrated the Feast of the Immaculate Conception when Bishop Olano announced the bombing at Sumai and released the congregation to find safety and secure themselves. Artero fled the church and returned home. From Hagåtña, he gathered his family into their truck and headed to their ranch in Toguag.

The following day, Artero’s son Jose began transporting people out of the village to safety while the Japanese bombed the island. With the surrender of the Naval government and the establishment of the new order under the Japanese, Artero, along with other island residents, became subjects of Japan and was issued a “passport” — a white cloth to be pinned to the chest.

In his autobiography, Artero, almost in hindsight, recounted how he was taken prisoner by the Japanese. On 7 January 1942, he was forced to leave his house and was taken to where other prisoners had been corralled at the cathedral’s sacristy. He was there for three days before being ordered across the Plaza de España to the school, Dorn Hall. He remained there for 11 days when on January 20, he was taken back to the plaza and then sent home.

Several days later as he was at the market slaughtering cattle, a high-ranking Japanese officer arrived and on seeing Artero there, he declared his surprise that Artero was not in Japan as expected with the other American prisoners. The officer was answered by a Shimizu (Kacha) that Artero had not been sent away because he “was good for the CHamorus and Japanese.”

During the Occupation, the Japanese took over homes, businesses and industries and removed cattle from ranches. The CHamorus were placed under forced labor to build roads and fortifications, and to provide food for the Japanese military. Artero was able to use his land in Upi to provide food for his family but also for others in need.

Unknown to him, his son Antonio was involved in hiding US Navy radioman George Tweed for two years. Tweed was the last American holdout that the Japanese unceasingly searched for and tortured anyone suspected of hiding him. Later, however, Antonio Artero was awarded the Congressional Medal of Freedom for his assistance with Tweed during the war, but Don Pascual in his biography declared if he had known what his son was doing for Tweed and the extent of the danger to his family, he would have stopped Antonio.

Artero continued in faith to pray to his statue of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel for the arrival of the Americans to liberate Guam from the Japanese. By 1944 the war turned and the Japanese became more desperate and more brutal in their treatment of the CHamorus. Artero, however, decided he and his family should defy the order to go to the concentration camps. Instead they went to the small cave at Pugua once occupied by Tweed. Through heavy shelling they watched the movement of ships and planes with their view of Ritidian Point to Urunao and all the way to Orote. They remained in the cave until August as the Americans bombed Guam. Artero truly believed that the power of the Blessed Mother saved him and the lives of his family through that dangerous time.

Golden years

Although Artero had lost much of his material wealth from the war, including the properties in Upi which were seized for military use (today known as Andersen Air Force Base), he still lived the rest of his life as he always had, dreaming large, and spending time with family. He became the first person from Guam to travel around the world in an airplane as he made his way back to his place of birth one final time before his death. With his second wife Teresa, and children Maria and Jose, Artero traveled to the Philippines, Calcutta, Syria, and Rome, where he had hoped to see the Pope. He visited family in Andalusia, Spain, and then relatives in New York, Washington, DC and San Francisco before returning to Guam. Retired, Artero spent much of his time in prayer. Before he died on 29 October 1956, he became a US citizen, fulfilling another life-long dream.

One dream he had not fulfilled was his plan to build Upi into a modern city. He had spent his life building his businesses, providing jobs and opportunities for other CHamorus through his butcher shop, cold storage warehouse and saw mill. But his desire for a planned city with shopping centers, hotels and a large airport never happened as his land passed into military hands. Today, however, the Arteros still own over 900 hectares of beachfront properties legislatively zoned as hotel/resort properties in northern Guam called Urunao.

A full life, Artero was a self-made man. Born into poverty, he traveled the world and found a home in Guam. His survival through three wars, the Spanish-American War, World War I and World War II, he attributed to his faith in God. In his biography, Don Pascual described himself,

Since my arrival in Guam, this has been my country. I am of Spanish blood, American spirit and CHamoru heart.

Don Pascual Artero y Saez

This sentiment lives on in his descendants today.

For Further Reading

Artero y Saez, Pascual. “An Autobiography.” Unpublished manuscript translated from Spanish to English in 1970. Mangilao: Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1948.

Mahone, Rene C. “Biography of Guam’s Last Spaniard: Don Pascual Artero y Saez (1875-1956).” Guam Recorder 4, no. 1 (1974): 16-19.