Editor’s note: This entry on “Political Development” by Carlos P. Taitano, distinguished statesman and former Guam Legislative Speaker, is a modified chapter from the book, Kinalamten Pulitikåt: Siñenten I CHamoru, Issues in Guam’s Political Development: The CHamoru Perspective, published by the Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1996. e-published with permission from the Department of CHamoru Affairs.

Guam’s colonized past under Spain

When the Europeans came to the Mariana Islands in the 16th and 17th centuries, they found a vigorous and highly developed community of people with a territory, economic life, distinctive culture and language in common. These Pacific islands were settled over 4,000 years ago by a group of people who came to be known as CHamorus. They were the first group of Pacific islanders to receive the full impact of European civilization when the Spanish began their colonization of the Marianas in 1668.

Colonization is the establishment of a colony, which is an area subject to rule by an outside power. According to international law prevailing at the time, the Spanish first came to the Mariana Islands. The discovery of lands that did not belong to a Christian prince constituted sufficient title for their appropriation.

After the “discovery” of the Marianas by Ferdinand Magellan in 1521, a colony was established in 1668 under the leadership of Spanish Jesuit missionary Father Diego Luis de Sanvitores. This colony lasted until 1898, when Guam was ceded to the United States under the treaty ending the Spanish-American War. The rest of the Marianas were sold to Germany by Spain.

The invasion of these islands by the Spanish in the late 1600s was a brutal violation of the sovereignty of this Pacific nation. The CHamorus resisted for 30 years but were finally defeated, losing their sovereignty to Spain. The Mariana Islands was not a place of barbarians. When the Spanish came, the CHamorus had levels of navigational expertise, for example, to match or surpass anything in Europe at the time.

Sovereignty is the condition of being politically free. The people of the Mariana Islands had supreme and independent authority for thousands of years before 1695, the end of the Spanish-CHamoru Wars. By the end of this resistance, CHamorus from all the northern islands were relocated to a few villages on Guam, while CHamorus on Guam also were displaced and concentrated in these villages. The Spanish did this to give them better control over the CHamoru people.

Throughout history, the sovereignty of a weak nation is lost to a strong nation by force or intimidation. Frequently, this sovereignty is passed around among the strong nations as they wage wars against each other. In rare instances sovereignty is restored to the weak nation that lost it in the first place. The weak nation, for whatever reason, sometimes consents to the transfer of its sovereignty to another nation.

The merciless and, at times, indiscriminate killing of the indigenous people, and the disease brought by the invaders, resulted in the near decimation of the native population. The cruel treatment that the CHamorus received came not only from the Spaniards, but from other Europeans as well. For example, two English buccaneers, John Eaton and William Cowley, visited Guam in 1685. The Spanish governor at the time, Don Damian Esplana, gave these Englishmen authority to kill as many natives as they pleased. Crowly, in his account of the voyage, reported that they were glad to engage in the sport. Before they left, they killed many CHamorus, often in a very barbaric manner.

The Spanish conducted a campaign to eliminate the traditional CHamoru religion and replace it with Spanish-Catholic Christianity. The Spanish had had a similar experience teaching the new religion to the indigenous peoples in North and South America. The ancient CHamoru practices, however, ran deep. For example, many CHamorus born under Spanish colonization in the 1800s, were baptized and married in the Catholic Church and considered themselves Christians. Yet they also may have firmly believed in supernatural spirits known as taotaomo’na. The ancient CHamorus practiced ancestor worship and some aspects of this religion continued to be practiced by some CHamorus.

The CHamorus were made to adopt Spanish customs and were subjected to Spanish laws, and eventually, a hispanicized society evolved. A map of Guam clearly points to Spain’s presence in the island’s past, reflected in place names, such as Santa Rosa Mountain, or street names, such as Hernán Cortéz Street. The CHamorus, too, have personal names that would be familiar throughout the Spanish-speaking world. In the Spanish tradition, a CHamoru usually has two family names, for example, Jose Duenas Castro. The first name, Duenas, which is the one commonly used, is the family name of Jose’s father; the second, Castro, is his mother’s family name. This order was changed by the Americans when they came to Guam following the Spanish-American War in 1898, so the individual would be known as Jose Castro Duenas. This seemingly simple name change was a difficult transition for some CHamorus.

Over the years, intermarriage between the indigenous people and people of varied ethnic backgrounds brought to the Marianas by the Spanish spawned a racially-mixed population. A different culture developed with the blending of the CHamoru way of life and the diverse characteristics of the newcomers.

In the early 1800s, some Caroline Islanders whose home islands were devastated by a typhoon were permitted by the Spanish to settle in the northern Marianas. Some years later, many CHamorus whose predecessors had been relocated to Guam in the early 1700s, returned to these islands that were the ancestral lands of their people. Some CHamorus came as representatives of the Spanish colonial government in Guam, while others came to build a new life for themselves and their families.

Guam under the American flag

In 1898, the United States captured Guam during the Spanish-American War. The Treaty of Paris, which ended the war, ceded Guam to the United States. The Northern Marianas were sold to Germany. Once again, the CHamorus suffered another devastating blow by colonial powers when the people and their land were divided. Families and relatives were separated and kept apart by political barriers.

Under the Treaty of Paris, the US was obligated to determine the civil rights and political status of the people of Guam. In spite of this treaty obligation, President William McKinley issued a two-sentence executive order placing Guam completely under the Department of the Navy. The officers appointed as naval governors of Guam exercised all legislative, judicial and executive authority. The entire island was designated a naval station and its harbor was declared a closed port. Each governor held dual appointments—governor and naval station commandant.

From the very beginning Guam’s importance as a strategic military base was recognized. All policies relating to Guam were formulated with its military value as the determining factor; human rights and fundamental freedoms of the native inhabitants were disregarded.

Guam was used by the Navy over the years as a vital center for communication and transportation, staging and deployment of troops, and a refueling and repair station. It was an important base for the bombing of Japan during World War II, as well as for bombing and other missions during the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Gulf War. Guam continues to be an important military base for the United States. As the westernmost American soil, it will increase in importance in the future as more units of the US armed forces are pulled out of foreign bases in the Far East and relocated to Guam.

Since Guam was acquired by conquest and ceded by treaty, the island became the absolute property and domain of the US. Many options were opened in deciding what to do with this new property. For one thing, the US could comply with Article IX of the Treaty of Paris, which stated:

The civil rights and political status of the native inhabitants of the territories hereby ceded to the United States shall be determined by The Congress.

Compliance could be in the form of a US congressional enactment of organic legislation for Guam with provisions for the protection of civil rights and the determination of a political status. Compliance could also be in the form of integration of Guam into the US political system, thereby granting CHamorus full US citizenship.

However, no action was taken to replace the military with a civilian government until half a century later, even though the island was peacefully captured and its people peacefully governed. Washington’s policy at that time was one of neglect, lack of awareness and insensitivity to the problems of this island community.

The Guam dilemma

Organic legislation pertains to the constitutional or essential law(s) passed by Congress organizing the government of the territory. When Guam was acquired in 1898, it was a possession or an unorganized area of the United States. When the Organic Act of Guam was enacted by Congress in 1950, Guam became an organized territory of the United States. The Organic Act took the place of the US Constitution as the fundamental law of the local government and bound the territorial authorities.

Historically, whenever a new land is acquired and organized as a territory, a representative is sent to the House of Representatives to represent that area. The usual interpretation of this policy is that the newly represented area becomes an incorporated territory and thereby is established as an “embryonic state.” This includes the non-contiguous territories, as was the case with Alaska and Hawai’i, which were incorporated territories before they became states of the Union in 1958 and 1959, respectively.

When the territory of Guam was created in 1950 under the Organic Act of Guam, it was made very clear by Congress that an unincorporated territory of the United States was all that was organized. The legislative history covering the passage of this act contains the statement that unincorporated areas are not integral parts of the US, and no promise of statehood—or a status approaching statehood—is held out to them. Therefore, not all parts of the US Constitution apply to the unincorporated territories. It has also been interpreted that in the absence of a precise congressional grant of rights, citizenship for the inhabitants of Guam is not the equivalent of citizenship in the various states of the Union.

The US, having supreme power over Guam and its inhabitants, could also sell Guam, give it away, or set it free (as in the case of Cuba), thereby restoring sovereignty. The US could also enter into an agreement with Guam for free association or commonwealth. Or, the US could do nothing. Unfortunately for Guam, the US picked the last option. This lack of congressional action lasted fifty years, causing extensive damage to the people of Guam. They were deprived of self-respect, dignity and liberty.

During the first fifty years under American rule, human freedoms, fundamental fairness and equality enjoyed by citizens in the continental US were not made available to the people of Guam. The basic democratic principle of government to function only by the consent of the governed, and the American tradition and history that government shall rest upon law rather than upon executive decree, did not inspire the Congress to apply these principles of democracy to Guam. Washington’s political leaders changed, but the attitude of the US government to the problems of Guam during this period remained the same.

Many Americans of this era generally shared with many Europeans the belief that non-European peoples were inherently inferior. Some of the US naval officers who came to Guam to rule were already prejudiced individuals, and kept the CHamorus uneducated and untrained, preventing their normal development. The Navy reinforced their contention that the CHamorus were inferior and consistently opposed any federal legislation granting US citizenship for the CHamorus on the grounds that the CHamorus had not reached a state of development that would call for US citizenship.

On the other hand, the two US territories in the Caribbean received more sympathetic attention than Guam. Puerto Rico was also acquired by the United States after the Spanish-American War. US military occupation of that territory ended just two years after the end of the war. An organic act was enacted by Congress, including the granting of US citizenship for the Puerto Ricans in 1917. A commonwealth status was created by Congress for Puerto Rico in 1950. The Virgin Islands was purchased from Denmark in 1917. In 1931, US naval rule was replaced by a civilian government and US citizenship was granted in 1932. The Virgin Islands Organic Act was enacted by Congress in 1936.

American colonialism and discrimination on Guam

The period of the early American administration on Guam prior to World War II reflected prevailing views of race and the importance of being a “white American.” For example, two separate schools for Guam’s children were established—one for Americans and one for CHamorus. There were two pay scales— one for Americans and a lower one for CHamorus. Many government and non-government areas were placed off-limits to CHamorus simply because some Americans did not want the CHamorus around.

Two generations of CHamorus were brought up having to endure the trauma of contradiction, learning about the US and its people as portrayed in textbooks, and experiencing an entirely different way of life on an island administered by Americans. The naval governors were ruling Guam not only politically, but also economically, controlling imports and exports and businesses. Yet, they would frequently blame the local merchants and farmers for the island’s imbalance of trade, for example, when the value of imported foods exceeded the value of exported products. This was a constant irritation to CHamorus who understood what was happening. But since Guam was a closed port under military rule, normal international trade practices could not function.

Additionally, since only elementary education in English was available and none in the CHamoru language, CHamorus were at a tremendous disadvantage and were effectively shut out from self-advancement and opportunity.

In the US, a nation of immigrants, birthright provides citizenship. Indeed, the so-called citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution specifies that anyone born on US soil is entitled to US citizenship—and this includes US-born children of illegal immigrants. Being born in Guam, however, had no such advantage. Instead, a CHamoru born on Guam was automatically placed in a low status compared to stateside citizens, subject to prejudice and discrimination by his military rulers. If a CHamoru remained on Guam, he could not grow out of this low status. Even if he could improve his performance at work, or go abroad and get a college degree and return to Guam to work, he could not rise from that low status.

For 50 years, CHamorus grew up under these conditions. There was no relief from Washington of this double-edged tragedy—not only colonial rule, but military colonial rule.

In Hawai’i and the US mainland, the name “CHamoru” became associated with someone inferior. Some CHamorus who managed to leave Guam often denied their CHamoru heritage when in the company of other people. After the recapture of Guam from the Japanese, many CHamorus, military and civilian, were returning to Guam and reporting on this state of affairs. It was at this time that the CHamorus on Guam made known to the US military authorities that they preferred to be called “Guamanians.” Someone suggested “Guamese,” like the Saipanese, but most people rejected that term. “Guamanian,” however, showed some connection to other Pacific Islanders, like the terms “Hawaiian” and “Tahitian.”

US Congress’ neglect of Guam

While leaders in Washington are not responsible for the gross violation of human rights on Guam in the past, the people of Guam can hold them accountable. The US Congress was obligated to determine the civil rights and the political status of the people of Guam under the treaty ending the Spanish-American War. Under the territorial clause of the US constitution, Congress was the sole legislative power for US territories. Under this power, Congress may deal with territories acquired by treaties, as in the case of Guam. However, Congress did not adopt legislation providing for a local government until 1950. By failing to act, Congress allowed the US Navy to rule the island of Guam under virtual martial law from 1898 to 1950. While Legislation enacted in 1950 and in subsequent years granted certain civil and political rights to the people Guam, the 52 years of gross violation of human rights suffered by the people of Guam remains a part of our history.

The US Congress has the obligation to address this matter and to come to some resolution. The Japanese-Americans, who were placed in US concentration camps during World War II, were successful in getting Congress to draw its attention to the predicament of these unfortunate Americans. Congress finally acted, acknowledging this injustice and awarding some monetary relief. As a start, the US Congress could return to the CHamorus a large portion of the lands on Guam now under federal control.

Taitano’s reflections

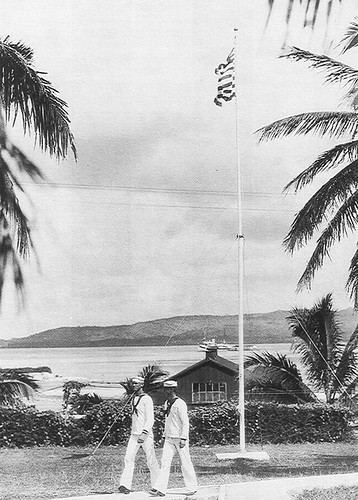

I left Guam in 1936 on the USS Chaumont to visit my brother in Honolulu. I paid about US$13.00 for steerage class accommodations which turned out to be a bunk with hundreds of sailors, soldiers and marines returning to the US from duty stations in China, the Philippines and Guam. My thoughts during that long journey of 3,300 miles were concentrated on the report that I was to make to my brother about the various members of our family and about our farm in Finegayan. I was totally unprepared for the things that I saw in Honolulu when I arrived there—namely, the way people lived in a free society. My first reaction upon landing in that Hawaiian society was extreme shock, followed by relief and joy of having left an island under military occupation into an entirely different world. It was a tremendous liberation.

The island I left was under a US naval governor. Military officers held all key or top level positions in the naval government of Guam. There was very little opportunity for CHamorus to acquire and develop the knowledge and skills to handle the affairs of their government. One naval governor took the trouble to explain that CHamoru children did not need the kind of education that American children needed. In Honolulu, it was pretty obvious to everyone that I met there that I was not the product of an American school. English was my second language and I spoke it poorly.

My first few weeks in Honolulu were like a crash course on the values and process of democracy and human rights. I was overwhelmed with surprise discovering the boundless opportunities for self-advancement that the US offered certain residents of Hawai’i. There was no military dictating what everyone did. There were no US marines stationed in the civilian communities. I saw many Pacific Islanders, like my CHamoru people, holding important positions in government and private industry. My brother was working at Pearl Harbor, side by side with people from the US mainland, getting equal pay for equal work. As I witnessed other differences between Guam and Hawai’i in the weeks and months ahead, I was filled with mixed emotions, delighted to be in Honolulu, but sad about the situation in Guam.

After a few years in elementary school in Guam, almost all of us went to work in our farms. One who was somewhat bright in school could become a school teacher or a minor clerk in the government. When enlistment as mess stewards in the US Navy was opened for CHamoru youths, there was a rush to the recruiting office. With no opportunity in Guam to develop their potential, many promising young men signed up for the Navy and left Guam.

However, the Navy did not allow enlistment of CHamorus in the regular Navy until the 1930s. But even then, CHamorus could only enlist as mess stewards. This policy applied even to a CHamoru with an American father. Enlistment for duty other than as a mess steward would be denied if his mother was a CHamoru—an echo of the black (African-American) experience in America. Even after Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese and enlistment in the US armed forces was encouraged all over the US, the Navy would not accept the enlistment of CHamorus then living in Hawai’i and the US mainland, except as mess stewards. On the other hand, CHamorus were accepted for enlistment in the US Army during World War II.

The United States Armed Forces recaptured Guam from the Japanese Imperial Forces in 1944 and today the liberation of Guam is celebrated every year in July. This event in 1944 also marked the beginning of the process of liberation of the CHamoru people from authoritarian US naval rule. The military government established in Guam after the defeat of the Japanese was significantly different form the prewar military government in that there was some relaxation of control over the CHamorus by the postwar military government.

The United Nations and decolonization

At the end of World War II, world leaders became concerned for many people throughout the world who had no voice in the enactment of laws that governed them, and who continued to live under conditions of inequality and without regard for the rights of the individual. The cost of World War II in terms of human suffering became more apparent, and the need for an international organization to seek peace, freedom, collaboration and security among nations arose. Fifty nations at the United Nations Conference on International Organization meeting in San Francisco between April and June 1945 drew up the United Nations Charter. On 24 October 1945, after this Charter had been ratified by all the major states of the world, the United Nations came into being. Its main purposes are: to maintain international peace; to develop friendly relations among nations; to cooperate internationally in solving international economic, social, cultural and humanitarian problems; and to promote respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The United States came out of World War II a very powerful nation and began to pressure other colonial powers to free their subject people, but, interestingly, failed to offer the same relief to its own subjects in its own colonies, the US territories.

In the Pacific, 14 island communities were freed from direct colonial rule. However, still on the agenda of the UN’s Special Committee of 24 on Decolonization are Guam and the French territories. This special committee is the main body concerned with progress towards self-determination and independence of all people under colonial rule. “Decolonization” is an international term in the United Nations system for the process of eliminating the colonial system in the world, and creating independent states from the former dependent territories. Self-determination is the right of a people to decide upon its own form of government without outside influence.

In the UN Charter, which was ratified by the US Senate in 1945, the US had an additional treaty obligation with respect to Guam as a non-self-governing territory. “Non-self-governing territories” is an international term for areas subject to the authority of another state.

In the Charter chapter entitled, “Declaration Regarding Non-Self-Governing Territories,” UN member states administering such territories recognized the principle that the interests of the inhabitants were paramount; member states also accepted as a sacred trust the obligation to promote their well-being to the utmost. To that end, they pledged to ensure the political, economic, social and educational advancement of the inhabitants of those territories, to develop self-government, and to assist the peoples in the progressive development of their free political institutions. The United States assumed the obligation to submit an annual report on Guam to the UN General Assembly.

Attempts to resolve the question about Guam

The administration of President Harry Truman, after the end of World War II, wrestled with the problems of Guam. The Truman administration decided early on that US citizenship for the CHamorus was long overdue. They remembered the loyalty of the CHamorus to the US during the 30 months of Japanese occupation on Guam. This administration also decided that the military government must be replaced by a civilian government. Independence, free association, commonwealth or statehood, however, were not even considered as a possible political status for Guam. There was only one status that they could recommend to the Congress—a middle ground status, which was not a state of the Union, nor one independent from the United States. The question about what to do about Guam as a US territory went back to when the island was acquired by the US back in 1898.

Sometime after the end of the Spanish-American War, a series of cases involving the newly-acquired territories from Spain came before the US Supreme Court for its consideration. Also known as the “Insular Cases,” the Supreme Court stated that the President had the right to establish and maintain control of recently conquered territories, even through the use of a temporary government, which would cease to exist once the need to establish such a government was not there anymore. This was not the case for Guam. Guam was peacefully captured and peacefully occupied. Therefore, the naval government of Guam should have ended very early in the 20th century, and been replaced by a civilian government. In contrast to Guam’s situation, to comply with its obligation under the Treaty of Paris, the US Congress quickly provided a local government for Puerto Rico in 1900.

Puerto Rico had moved from a possession to an organized territory when a civil government was created by Congress. Under a compact proposed by Congress and ratified by a referendum vote by the people of Puerto Rico, Puerto rico drafted and adopted its own constitution, creating a commonwealth.

Decades later, the Guam Organic Act of 1950 sent to Congress by President Harry Truman created an unincorporated territory of the United States with limited home rule, no participation in the presidential elections, no representation in the US Congress, and the appointment of the Guam governor in Washington. Since only a territory was created, rule by Congress continued under its plenary powers as provided by the territorial clause of the US Constitution. These offerings still, were a far cry politically under naval rule.

However, throughout the long period of military rule, there were some naval governors who did try to address the political concerns of the CHamoru people and introduce some semblance of democracy. For example, the people were eventually allowed to vote for representatives to the Guam Congress, which was strictly an advisory body for the naval governor. Previously, the governor appointed the members. The Guam Congress at the time was a bicameral house. The Council was the upper house and the Assembly was the lower house. But since the governor of Guam had executive, legislative and judicial authority, any action by the Guam Congress had to meet his approval. Of course the governor could take back whatever was granted, including the privilege of sitting in that Guam body.

Taitano and the Guam Congress Walkout of 1949

In 1948, the Secretary of the Navy granted what he described as an interim legislative authority pending enactment by the US Congress of legislation embodying law-making rights. When the Guam Congress attempted to exercise these interim legislative rights in connection with an economic inquiry, the naval governor intervened and prevented the Guam legislators from discharging their duties. The lower house of the Guam Congress, the Assembly, voted to adjourn until the US Congress acted on a proposed bill for an organic act and civil government for Guam.

The decision to stage a walkout was not easy for the assemblymen to make. All activities in Guam, including communication with the outside world, were under Navy control. Before entering the island of Guam, everyone, including CHamorus, had to first obtain a security clearance from the Navy. The assemblymen were fearful of the repercussions. Retaliation could be quick and severe. Nothing even remotely common to this revolt ever occurred during the 50 years of naval government.

Ruled for centuries by force and trained in a habit of uncomplaining submissiveness, many CHamorus tried to prevent this outward manifestation of their long-standing grievances. But throughout this period of military rule, there was a lack of national concern for the CHamorus. The American people knew nothing or very little about Guam. Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, geographically close to the US mainland, had friends in the US congress and the business community, and the support of several influential newspapers in their struggle for home rule.

After my discharge from the US Army in 1948, I ran for a seat in the Guam Congress and was elected an assemblyman from the village of Mangilao. I was convinced that if the political neglect of our people by Washington was brought to the attention of the American people, Congress would act. The revolt provided the vehicle for the dissemination of information concerning the problems of Guam.

Several months before the revolt took place, I contacted two newsmen, one from the Associated Press and the other from the United Press International, who were on Guam covering military news. I invited them to my home to Mangilao, where I gave them a brief account of American rule since 1898. I asked them to publicize the complaints of the CHamoru people. Immediately after the walkout I sent a report by cable to these newsmen in Honolulu, where they were waiting for word from Guam. After the first report was spread all over the US, the Navy could not stop the other reports that continued to flow to Honolulu for the next two weeks.

The Guam revolt was carried by major US newspapers, such as the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Christian Science Monitor. The Honolulu Star-Bulletin called it “Guam’s Boston Tea Party.” The revolt stirred renewed interest from Washington to propose the transfer of Guam from a naval government to a civilian government. Newspaper editorials demanding congressional action also began appearing.

Six months after the walkout, the naval governor was replaced by a civilian governor. Pursuant to the recommendation of his four departments, President Truman issued Executive Order 10077 on 7 September 1949 transferring the administration of Guam from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of the Interior. The US Congress, with executive support, moved toward the passage of an organic law for Guam. On 1 August 1950, President Truman signed the Organic Act of Guam at the White House.

Interestingly, many members of Congress and officials of the Department of the Interior had previously expressed their doubts that the Guam act would pass at that time in view of the Navy’s opposition and the beginning of the Korean War. They reported that the revolt on Guam triggered a series of executive and congressional actions leading to the early passage of the Guam act. Indeed, this was the first congressional enactment on the political status for the people of Guam.

Provisions of the Organic Act of Guam

Through the Organic Act the Department of Interior took over from the Navy. The Department of Interior, created in 1849, was one of the executive departments of the United States. Its functions are conservation and development of natural resources of the US and its territories, and guardianship of the Native American Indians.

In the Guam Organic Act, an organized government was created for the first time for the people of Guam, but with limited home rule and with substantial control from Washington. It conferred American citizenship on the CHamorus; provided a bill of rights; created a legislature and established a judiciary system permitting appeals in certain cases to the US federal system. These were substantial gains, considering over 50 years of political neglect. The Organic Act granted US citizenship to all persons living in Guam on 1 April 1899 and those born in Guam after that date and their descendants.

Although the Organic Act conferred US citizenship on the CHamoru people, it did not give Guam residents equal rights to those enjoyed by other US citizens. Also it must be kept in mind that this was a unilateral action by Congress. Under the Constitution, Congress has the power to modify or revoke the grant. The Organic Act also did not provide for a Guam representative in Congress or for the local election of the Guam governor. Washington continued to appoint the Guam governor. Further, there was no provision allowing the participation of Guam residents in the election of the president and vice-president of the United States.

Many problems of Guam were not resolved with the enactment of the Guam Organic Act. The CHamorus continue to advocate the removal of federal laws that impede or restrict the island’s economic growth. These laws clearly were enacted for the benefit of US mainland commercial interests or for the benefit of federal establishments. Such federal laws were enacted whenever Congress wished, irrespective of the wishes of the CHamoru people. There were also the indignities and inconvenience suffered by the CHamoru people in being required to obtain the Navy’s permission before they could return to their homeland.

One of the federal impediments is the “Jones Act.” The application of US vessel documentation laws mandate that certain vessels (which includes commercial fishing vessels) used for certain purposes, must be built within the United States. The special interests protected by the Jones Act are not shared by Guam. Guam is closer to Asian countries of the Pacific rim than to the US mainland. There are times when foreign-built and foreign-owned vessels offer Guam merchants better service at lower freight costs. However, Guam merchants are prohibited from hiring them.

Another impediment was the Navy’s security clearance to enter or exit Guam. The security clearance, though, was finally lifted in 1962, opening the door for tourism and economic growth for Guam. The inability of Guam’s people to elect their own leaders eventually was resolved almost two decades after the Organic Act was signed. In 1968, the US Congress enacted a law which provided for the popular election of the governor and lieutenant governor. However, without waiting for the US Congress to authorize a delegate from Guam, the Guam Legislature in 1964 provided for an elected representative in Washington. In 1972, a non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives was authorized by Congress.

When the question of governorship for Guam was being considered, a member of Congress made the statement that the United States had a large investment in military equipment and installations in Guam and therefore, Congress could not allow Guam to elect as their chief executives one of its own people. The Congressman was quickly reminded, however, that such a situation did not seem to cause any problem in California, which also had large military investments and installations.

The question of Guam’s political status

The question of statehood for Guam was frequently brought to the attention of Congress. To forestall any movement toward statehood, certain members of Congress offered the suggestion that Guam be made part of the State of Hawai’i, though situated over 3,000 miles away. Needless to say, this idea was strongly opposed by the people in Guam. Some suggested that Guam and the US Trust Territory could probably function as a state of the Union. Opposition to this idea came principally from the US Senate. The diverging political movements within the various districts of the Trust Territory ended further discussion on this subject very quickly.

Those who opposed statehood for Guam pointed out that Guam has a small land area and a small population. Further, they claimed Guam could not assume the financial responsibility of a state. However, history records that 17 of the states were admitted to the Union when their populations were less than that of Guam, and some were less able than Guam to assume the financial responsibility of a state.

Guam looks with disappointment and envy at its neighboring islands, which were formerly under US trusteeship and now have self-government—and which came under American administration almost 50 years after Guam. The US allowed these islanders to determine for themselves what they wanted for their people. The Northern Marianas, for example, chose commonwealth status, while the other island groups chose free association.

In 1986, the Guam Legislature enacted a law which authorized Guam’s first Constitutional Convention (ConCon) for the purpose of reviewing and making recommendations on proposed modifications to the Guam Organic Act. The proposed constitution was sent to Congress, but it did not meet that body’s approval.

The 12th Guam Legislature created Guam’s first Political Status Commission in 1973. For the purpose of continuity, the 13th Guam Legislature created another Political Status Commission in 1975.

Based on the work of these commissions, a plebiscite on political status was held in 1976. A plebiscite is a vote, or decree, of the people, usually by universal suffrage, on some measure submitted to them by some person or body having the initiative. In 1976, the Guam Legislature gave the voters of Guam the opportunity to select by plebiscite their preferred political status. Out of the options presented to the people, the voters selected “Improved Status Quo.” This seemed to suggest that the people of Guam wanted to see a status for Guam similar to the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas.

While the Political Status Commission was trying to fulfill its mandate regarding the island’s political status aspirations, in 1976, the US granted Guam the authority to frame its own constitution, but had to stay within the existing territorial-federal relationship. The US required that the proposed constitution recognize and be consistent with the sovereignty of the US over Guam and also recognize the supremacy of the provisions of the US Constitution, treaties and laws of the US applicable to Guam.

A new draft constitution was drawn up by the second Constitutional Convention, but this draft was embroiled in controversy which came from many quarters on the island. For various reasons, the constitution was overwhelmingly rejected in an island-wide referendum. Many viewed the draft constitution as nothing more than a continuation of the present status.

The Guam Legislature then created the Commission on Self-Determination in 1980 and re-established it in 1983. In two island plebiscites, the voters were asked to select commonwealth, statehood, status quo, incorporated territory, free association, independence and any other status they wanted. The preferred option by the voters who participated was commonwealth. Independence received relatively few votes. In view of the extent of Americanization of Guam and the acceptance by the people of Guam of the United States as the nation to which they owe allegiance, it follows that for the present, independence is clearly not the goal of the people of Guam. However, should a future plebiscite be conducted, independence will be an option.

In the US, “commonwealth” is simply another name for the state government. An example is the Commonwealth of Virginia. Puerto Rico and the Northern Marianas, however, are both commonwealths. Each negotiated with the federal government for more local control of their internal affairs. The Northern Marianas went one step further by securing a provision for “mutual consent” in its covenant (a formal agreement) with the United States. Mutual consent is the approval of what is proposed by another, pursuant to the agreement. The mutual consent provision requires both parties to agree to any change or decisions to dissolve the covenant. This is the first time that the US agreed to a limitation of its power.

From the 1982 plebiscite, Guam sought a similar limitation on federal power in the Guam Commonwealth Act, drafted afterward. Any proposal for a change or dissolution of the Guam Commonwealth Act must be approved by both parties to the agreement—in this case, the United States and the Commonwealth of Guam. The US would limit its authority in that no change to the act can be made without the mutual consent of the US government and the government of the Commonwealth of Guam.

The Commission on Self-Determination completed the Draft Commonwealth Act in 1986. After adoption by the Commission and approval by the people of Guam in a referendum, the draft act was sent to Congress in 1988. The Commission felt that the best and quickest way to bring about commonwealth status was to send the draft act directly to Congress. To the Commission, going through the executive department as was done in the case of the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas, would take a long time to obtain final approval. If passed by the US Congress the Guam Commonwealth Act, it was believed, would result in a substantial change in status for Guam, from an unincorporated territory to a commonwealth.

The Guam Commonwealth Act would expand the number of provisions of the US Constitution that apply to Guam by extending the 10th Amendment to prevent federal intrusion into the Commonwealth’s internal matters, and the first sentence of the 14th Amendment to affirm the status of Guam’s residents as citizens of the United States at birth. However, there would have been certain restrictions placed by the act.

The act authorized a Guam Constitution to be adopted by the people of Guam as the supreme law of the Commonwealth. This Guam Constitution, as written, “shall recognize, and be consistent with, the sovereignty of the United States over Guam, and the supremacy of the provisions of the Constitution, treaties and laws of the United States applicable to Guam.” In addition, the inherent right of self-determination for the indigenous CHamoru people of Guam would be formally recognized by Congress. The exercise of this right would be detailed in the Commonwealth constitution. The act would authorize special training programs and employment opportunities and participation in federal programs for CHamoru inhabitants of Guam.

During the political status discussions, the CHamoru indigenous rights advocates demanded that only the CHamoru people be allowed to vote on the question of self-determination for Guam. This would have excluded thousands of voters who moved to Guam either from the US mainland or from foreign countries (those from foreign countries are eligible to vote in Guam through the process of US naturalization and by becoming residents of Guam).

As mentioned, if the Guam Commonwealth Act had been passed by the US Congress, a constitutional convention was to be assembled to draft the constitution of the Commonwealth of Guam. This draft would then be submitted to the indigenous CHamoru people of Guam for their vote, in the exercise of their inherent right to decide upon their own form of government. It is conceivable that the general Guam electorate would have participated in the drafting of the constitution.

Who is “CHamoru?”

In international law, the recognized government of a particular area determines not only who is eligible to vote, but also who is entitled to certain rights, including indigenous rights. Since the Guam Commonwealth Act recognized the right of self-determination by the indigenous CHamoru people of Guam, it became necessary to determine “who is a CHamoru?” The Guam Commonwealth Act defined the indigenous CHamoru people of Guam as all those born in Guam before 1 August 1950 and their descendants.

When the Spanish colonized the Mariana islands, they called the inhabitants Mariana Indians, or “marianos” to distinguish them from American Indians. In government and church records, the Spanish consistently identified the people that they brought to the Marianas according to their country of origin. Although the Spanish referred to the native population as “Indians,” the indigenous people of the Marianas referred to themselves as taotao tano’, which was their way of indicating a native of an area, as opposed to an outsider. Taotao tano’ means “people of the land.” By the late 1800s, the population of the Marianas had become so mixed racially that the Spanish discontinued the policy of racial or ethnic identification and began the practice of calling all inhabitants “CHamorus.”

From the time the Americans came in 1898 until the recapture of Guam during World War II, “CHamoru” was used to identity the people of Guam. Shortly after the Americans returned to the island, the CHamorus made known to the military authorities that they preferred to be called “Guamanians.” This resulted in a confusion of identity. Some called themselves Guamanians, some CHamorus. Guam leaders started explaining that a Guamanian is anyone who is a legal resident of Guam and a CHamoru is one of the indigenous people of Guam. At this time in the 1960s and 1970s, there was renewed interest in traditional island culture and a rediscovery of their taotao tano’ pre-contact past.

Conclusion

The people of Guam must not overlook the contributions in development of Guam made by the island’s political leaders in the late 1940s. Growing up under a military government that provided limited opportunity for self-advancement, this small group of heroic CHamorus managed to convince Washington that the political neglect of the people of Guam could no longer be tolerated. The United States Congress responded by enacting the 1950 Organic Act of Guam, establishing the first step in Guam’s political evolution.

The creation of this new political status, the Commonwealth of Guam, is not the final step in the political development of Guam. Future goals are, possibly, the reintegration of the Mariana Islands and statehood for the unified Marianas.