Iron used for tools

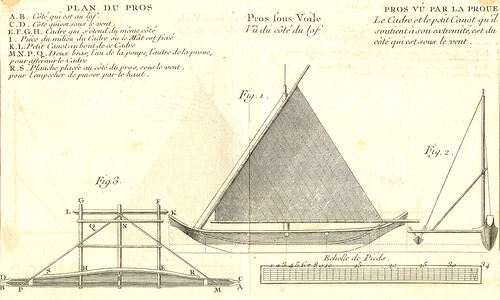

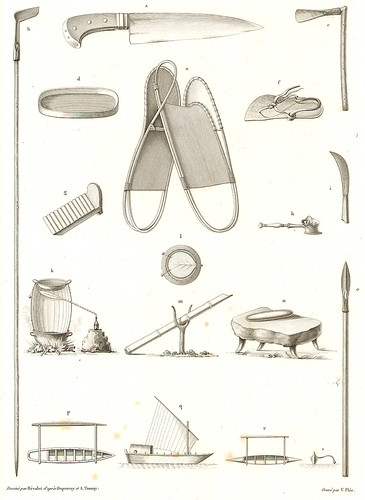

The matao fashioned the iron they acquired from trading with visiting ship crews into traditional tools, including punches, drills, fish hooks and adze blades. The most prominently mentioned application was canoe construction, a major preoccupation of high status men. The Marianas outrigger canoe played a vital role as the integrating mechanism for the islanders’ cultural unity, connecting their tano’ tasi (land of the sea) via inter-island transportation, communication and trade.

The craft also functioned as a major subsistence tool, providing the means of harvesting near-shore and pelagic fish, gathering shellfish and other marine and seabird products from distant reefs and shoals, as well as transporting foodstuffs and raw material between villages and islands. The ubiquity and beauty of these canoes, painted with an orange ocher, white or black, and propelled by triangular mat sails, led early Spanish visitors to call the islands Islas de las Velas Latinas – Islands of the Lateen Sails.

High-ranking men organized canoe construction but gathering and preparing the materials required extensive community time, effort and teamwork. The sakman, the largest ocean-going craft observed by visitors, was typically 26 to 28 feet long. There also were other smaller types of sailing and paddling canoes. Traditional sakman construction used wood from the breadfruit tree (Artocarpus mariannensis and Artocarpus incisus); palo maria (Calophyllum brasiliense); as well as bamboo cane. Men felled, dressed and shaped these raw materials into hulls, side planks, masts, booms, spars and outrigger poles and floats. Women processed pandanus fiber for the sails and wove them so finely that the Spanish compared them to “coarse linen” and the Dutch likened them to “dressed sheepskin.”

The islanders drilled, punched and gouged holes in the edges of hull sections and side boards and secured them to adjoining pieces with coconut fiber sennit, looping this binding through the holes and securing the joint tightly. A paste of lime and coconut oil sealed the holes and seams. The abundance of stone and shell perforators and drills as well as bone awls and augers in Marianas archeological sites attest to the widespread use of boring tools in pre-contact society. Because large nails, clusters of smaller ones and pointed metal could more efficiently accomplish the multiple hole-boring needed for canoe construction, the matao reinterpreted them as punches, perforators and drills.

Islanders on Rota also made fishing hooks of nails they acquired from the Santa Margarita, according to Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora, a Capuchin friar who sojourned there in 1602. The cleric also noted that islanders who previously used flint knifes had iron ones from the Santa Margarita to cut open fish.

Knives, machetes and cutlasses were also used to clear fields for swidden gardens of yams, plantains and taro. The Franciscan friar Antonio de los Ángeles, who sojourned on Guam in 1596, noted the islanders “value iron very highly to work their fields with, to sow their rice and a few local vegetables, which they use to sustain themselves.” Iron knives, machetes and cutlasses also were added to the islanders’ array of armaments.

Toolmakers on Rota shaped and sharpened iron without forging in the early 17th century, Fray Juan Pobre reported, describing how they worked the metal:

with pure force in accordance with what they need, by taking some very strong cobblestones and with pounding they make their hooks and knives without fire [forging] and they know very well how to grind them so that they can use them to make their ships and things they need.

Islanders learned blacksmithing

Forging was likely in use by the 1640s. A few Concepción beachcombers reportedly made a living forging iron, and Choco, a Chinese castaway who arrived in 1648 on a ship plying the Manila-Ternate trade “earned a tolerable living by making knives and axes from iron hoops, for he operated a forge.”

The introduction of forging enabled the islanders to more efficiently adapt hoop iron to their most commonly used wood-working tool – the hafted adze. As an account in the 1640s noted, the islanders “desire … iron because with it they build their boats, turning the iron into hatchets for cutting the wood.” The shouldered adze, typical of the Marianas, used blades of sharpened segments of basalt or giant clam (tridacna) shell, which were slotted into the head, with their cutting edge perpendicular to the line of the handle, and firmly secured by a sennit binding.

Forging allowed the matao to heat and cut barrel hoops into segments, as well as flatten and shape pieces of hoop iron into adze blades and knives. A Jesuit chronicler described part of the process in the 1660s: “So as not to be short of building tools, they sharpen pieces of iron hoops to a polish with a hard stone…and then they place it into a [fire] hardened stick and tie it tightly.”

Iron-bladed adzes were especially useful in hewing and shaping canoe sections and planking. As the same Jesuit noted, “whatever is to be built, it is a lengthy process, for they sweat at the task for years with slow blow [and] obstinate patience. Because they lack [metal] tools, especially the saw, they can make only one board out of a whole tree [log], the rest flying off as chips.” Iron tools probably were also used for felling and dressing timber and bamboo for community buildings and family residences.

Iron became an exchange item

All forms of iron also were regarded as a valuable commodity that could be offered along with traditional exchange mediums, such as sea turtle shell and rice, in reciprocal exchange customs, alliance-building gifting and compensation for goods and services. Accumulating iron goods as “a stock of working capital” could allow kin-groups to use gift presentations to produce a range of services, from traditional labor to the creation and maintenance of political alliances and assistance in warfare.

The acquisition of iron became a measure of personal prestige and status during this period. The clerical sojourner de los Ángeles noted that trading with Spanish ships for iron was counted as a major life achievement. When relatives honored a deceased matao:

[t]hey praise him for his skill at fishing and the great strength with which he used to throw spears and shoot the sling, that he would go to the Spanish ships passing by there and bring back iron, that he built canoes, gave feasts to which he invited the town people, and that he owned many tortoise shells….

The possession and manipulation of iron goods by members of the matao was a manifestation of their status, reflecting the existing social order, but may have intensified indigenous dynamics, including social differentiation, within this social strata. As a Jesuit reported from a village on Guam’s northwest coast in 1669:

So far nothing precious has been discovered in these islands. What they accumulate here is iron and tortoise shell; he who has the greatest quantity of them is the most powerful.

Trade opened the way for colonialism

Because the iron trade and repatriation services were the matao’s sole regular source for iron goods, the islanders’ relationship with the galleon trade offered a receptive milieu for missionaries dedicated to religious conversion, social transformation and political consolidation. And the Royal Patronage of the Indies, or Patranado Real, provided a tool for missionaries to gain the material and organizational resources for colonial intrusion. This arrangement between the Papacy and the Spanish Crown provided for the promotion and defense of the Roman Catholicism in the New World (and the Philippines), requiring Spanish officials to support the Church but also allowing them to use missionary work as an arm of the state to acquire and administer new colonies.

The chief architect and driving force behind the 1668 Spanish mission, Father Diego Luis de San Vitores, employed images, resources and practices generated by the iron trade “culture of culture contact” to help persuade Spanish officials and island leaders to support his initiative. A high-born Castilian with influential family and Jesuit connections at Court, San Vitores was a talented and visionary evangelist, seeking to emulate Jesuit pioneers in Asia such as Francis Xavier and eager to proselytize non-Christian people. In the Philippines, he felt unfulfilled ministering to the spiritual needs of established Christian communities, disappointed by what he viewed as Manila’s retrenchment from the Moluccas and Mindanao, and saw little opportunity for direct mission initiatives in Japan or China.

San Vitores had witnessed the matao iron trade on the 1662 Acapulco ship San Damián and learned about the islanders from officers and crewmen who had lived among them. Aware of earlier Spanish exploration in the region, including failed colonization attempts in the Southwest Pacific, San Vitores developed a proposal for opening a new frontier for missionary activity and imperial expansion. He argued that the conversion and consolidation of the Marianas, which he believed was long overdue, would not only provide for the islanders’ spiritual salvation and material advancement, but also allow the islands to serve as a base to extend Christian dominion and Spanish rule to other “unclaimed” archipelagos of Oceania.

The Marianas and islands north of them might also serve, San Vitores suggested, as stepping stones to re-enter Japan, where the Jesuits had developed thriving Christian communities until the Tokugawa suppression and seclusion policies closed that nation to European clergy in the 1630s.

To counter the many officials who viewed a mission to islands without precious metals or valuable spices as a drain on resources needed for the Philippines, San Vitores downplayed the expense and danger of the enterprise, saying it required only a small contingent of priests and assistants and could be delivered and supported by the regular visits of the Acapulco ships.

He emphasized the kindly and peaceful image of the matao that had emerged from castaways and clerics, stressing how the iron trade had made the islanders well-disposed toward the Spanish. He asserted the islanders’ fear of losing “their well-established friendship and trade with our galleons, the sole source of iron and other necessary goods,” would assure safe treatment. The Acapulco ships, he added, could provide whatever “just punishment” might be needed if missionaries were harmed.

San Vitores’ allies at Court helped to win a royal decree in 1665, ordering officials in Mexico and Manila to provide the resources and assistance for the mission. He recruited two repatriated Filipino survivors of the Concepción wreck who had spent decades among the islanders – Francisco Mendoza and Estevan Diaz, who taught San Vitores what they knew of the islanders’ language and customs. They joined his mission and Mendoza became its principal interpreter. A few Concepción beachcombers also joined the mission as translators, cultural informants and assistants.

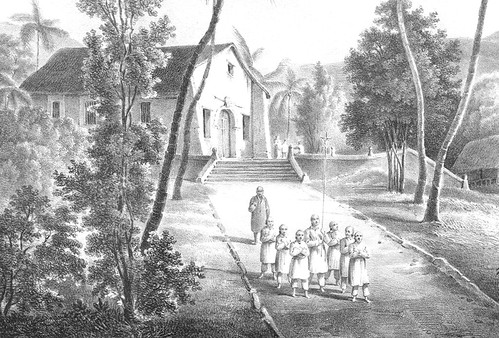

San Vitores, whose 50-member mission reached the Marianas on 15 June 1668 on the Acapulco ship San Diego, chose Guam because it was the largest, most populated island in the archipelago and offered anchorages on its western coast. His choice of Hagåtña may have been based on its reputed high status and because its paramount chief, Kepuha, had a history of friendship with the Spanish. Pedro Jiménez, the Concepción beachcomber who had become a favorite of several chiefs on Guam, came aboard the galleon the day after it arrived and reportedly assured the Jesuits that their request to establish a mission would be favorably received.

To officially broach the proposal, San Vitores selected an unarmed contingent of two priests, the interpreter Mendoza and a Spanish galleon officer. Kepuha received them in a large canoe-house near the shore, where the priests “kissed” (nginge’) the chief’s hand and passed their hands over his chest, signs of customary respect, and presented gifts “from the King of Manila” who wished to be Kepuha’s friend. The interpreter told the chief the missionaries wanted to teach them the way to heaven.

The presence of the 300-ton San Diego, anchored off their village, may have seemed favorable to Hagåtña’s leaders. Hundreds of villagers were trading with the ship’s crew and passengers during the visit. Missionaries and galleon officers, including the captain, had gifted barrel hoops, knives and hatchets as well as highly valued sea turtle shell to chiefs and other members of the matao during the initial meetings. If the chiefs accepted the mission, other Spanish ships might regularly make port at Hagåtña to resupply the group, deliver and repatriate clerics, provide rewards for the safe treatment of the priests, and barter with their kin groups and associated lineages and villages. If the annual trade were conducted in their territory, the Hagåtña chiefs would effectively control the archipelago’s access to the iron trade. Moreover, with their trade goods and superior weapons, the Spanish would make powerful friends and allies in Hagåtña’s rivalries with other villages and districts.

Conversely, if the chiefs declined to host the mission, a rival village, district or island might seize the opportunity and gain the advantage. As historian Francis X. Hezel has noted, “The Spanish, with the prestige that their muskets and persons conferred, were a potentially lucrative possession, a force that invited manipulation by CHamoru political factions for their own political ends.”

Many chiefs reportedly regarded San Vitores’ request as a positive overture, avidly requesting priests for their villages, possibly interpreting their arrival within the tradition of caring-for-and-returning well-behaved castaways and clerics. Because the Jesuits were closely associated with the Acapulco ships and galleon iron trade, other chiefs may have viewed the mission as a trading colony, envisioning Hagåtña, which had grown in prestige during the 17th century, as a commercial hub for the islands. Though the exact calculus is unknown, Kepuha granted the missionaries permission to reside in Hagåtña under his protection.

Warm welcome turns into sporadic resistance

Despite the auspicious welcome and an initial flood of infant baptisms and adult conversions, sporadic resistance soon developed. Viewing themselves as civil administrators as well as religious proselytizers, the missionaries’ social and political agenda grew intrusive, attacking customs and institutions and intervening in village disputes and wars. Conversions among several kin-groups was countered by violent confrontations with others and the deaths of laymen, priests and islanders.

After San Vitores’ was killed by Matå’pang, a matao chief on Guam in 1672, the Jesuit mission evolved from a non-violent conversion and consolidation effort, which had used its few weapons for self-defense, into a militant colonizing agency backed by a governor and garrison of troops who used arrests, executions and village destruction to force conversion and compliance.

By the 1680s, the islanders’ give-and-take relationship with the Spanish had become predominantly a process of forced acculturation. Islanders were gradually resettled in several barrio-villages, where Spanish conquest culture reshaped their way of life and epidemics of introduced diseases decimated the population, reducing it from about 40,000 in 1668 to fewer than 4,000 by 1704.

Throughout this struggle, however, a significant number of converts from both high and low status groups voluntarily adopted Christianity, staunchly supported the missionaries, played pivotal roles in saving the mission from annihilation and laid the foundation for a transformed society. The ostensible benefits of conversion and Spanish rule, as asserted by missionaries, colonial officials and some converts, have weighed heavily in traditional interpretations of the Marianas’ European contact period.

The process of accommodation, it is argued, melded introduced ideas and practices with indigenous beliefs and customs, “civilizing” the islanders; transformed a highly stratified social structure into a less rigidly hierarchical society; shielded converts from brutal colonial soldiers and rapacious governors; and brought them into the international community as members of Spain’s regional empire and the global communion of the Roman Catholic Church.

In polar opposition, anti-Spanish and anti-colonial interpretations emphasize the religious oppression, military conquest and subjugation, which led to the loss of indigenous rights and generated radical social disruption that contributed to drastic demographic decline.

Earlier encounters shaped by trade, not conquest

Both of these paradigms seek to encompass the extensive period of pre-mission cultural interaction. But the Spanish colonization of the Marianas was not implicit in the first 150 years of European contact. Rather than a violence-dominated prelude to conquest or an era of nascent interest in Christianity, the early period of encounter was shaped by the iron trade – a time of dynamic cultural interaction during which the matao eagerly appropriated this new resource and integrated its products into indigenous production and exchange systems. The islanders vigorously defended their territorial control and prerogatives during this interaction. This was exemplified by their dealings with aggressive or violent officers and crew (such as the situation of the Santa Margarita), resisting armed incursions and punishing the threatening or violent behavior of ship visitors and castaways.

The matao functioned as a creative elite, receptive to external influences via trade interaction, and as cultural innovators, eager to adopt and integrate new imported technology and willing to adjust attitudes and behavior to accomplish that goal. Significantly, this process of islander-led adaptation did not require subordinating indigenous rights and customs to European demands and impositions.

The unforeseen consequences of the iron trade, however, were entanglements — engendered by the matao’s dependence on the galleon trade for iron and complicated by indigenous sociopolitical dynamics — that provided preconditions for the missionization of the Marianas. The belated recognition by many kin-group leaders that the mission’s goals were hostile to their interests is understandable in light of their enculturated experience with the iron trade and the caring for-and-return of castaways tradition that had accommodated previous religious sojourners and galleon castaways.

The Jesuits’ diplomatic entrance and proselytizing strategy further masked the missionaries’ ultimate goals. Yet, even after the colonial challenge became apparent, the islanders’ responses were varied, fragmented and often ambivalent. Armed confrontations responded to Spanish actions or incidents affecting a specific kin-group or village, rather than the overall destabilizing presence of a colonizing agency.

There was no island-wide unified armed resistance, even on Guam, the colonizers’ base of operations. The islanders’ decentralized politics, with its inter-village and inter-island rivalry and shifting networks of kin, village and district alliances, some of which sought to exploit the Spanish presence for advantage, virtually precluded a centralized, coordinated response.

However, kin-groups that responded with an “accommodation by appropriation” strategy, that is, conversion, adaptation and co-optation, survived the conquest period and their descendants prevailed over the centuries. Their adoption of Hispanic, Filipino and American cultural elements, while maintaining a distinct language, ethnic identity and adaptive culture, is reflected today in the islands indigenous Chamorro people.

The Matao Iron Trade entries

- Part 1: Contact and Commerce

- Part 2: Galleon Trading and Repatriation

- Part 3: Appropriation and Entanglement

For further reading

Campbell, I.C. “The Culture of Culture Contact: Refractions from Polynesia.” Journal of World History 14, no. 1 (March 2003): 63-86.

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Diaz, Vincent M. “Simply Chamorro: Telling Tales of Demise and Survival in Guam.” The Contemporary Pacific 6, no. 1 (1994): 29-58.

–––. Repositioning the Missionary: Rewriting the Histories of Colonialism, Native Catholicism, and Indigeneity in Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2010.

Driver, Marjorie G. “The Account of a Discalced Friar’s Stay in the Islands of the Ladrones.” Guam Recorder 7, no. 1 (1977): 19-21.

–––. “Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora and His Account of the Mariana Islands.” The Journal of Pacific History 18, no. 3 (1983): 198-216.

–––. “Cross, Sword, and Silver: The Nascent Spanish Colony in the Mariana Islands.” Pacific Studies 11, no. 3 (1988): 21-51.

–––. “Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora: Hitherto Unpublished Accounts of His Residence in the Mariana Islands.” The Journal of Pacific History 23, no. 1 (1988): 86-94.

García, Francisco. The Life and Martyrdom of Diego Luis de San Vitores, S.J . Translated by Margaret M. Higgins, Felicia Plaza, and Juan M.H. Ledesma. Edited by James A. McDonough. MARC Monograph Series 3. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 2004.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. “From Conversion to Conquest: The Early Spanish Mission in the Marianas.” The Journal of Pacific History 17, no. 3 (1982): 115-37.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ., and Marjorie G. Driver. “From Conquest to Colonisation: Spain in the Mariana Islands 1690-1740.” The Journal of Pacific History 23, no. 2 (1988): 137-55.

Lévesque, Rodrigue. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vols. 1-5. Québec: Lévesque Publications, 1992-1995.

Quimby, Frank. “The Hierro Commerce: Culture Contact, Appropriation and Colonial Entanglement in the Marianas, 1521-1668.” The Journal of Pacific History 46, no. 1 (2011): 1-26.

Thomas, Nicholas. Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.