CHamoru/Chamorro World View

Table of Contents

Share This

Concepts of heaven and hell are foreign

The idea of the world being divided into different realms, as was common in the CHamoru/Chamorro view after Christianity was introduced, is one promoted or at least influenced by Spanish missionaries in the 17th century to aid in their conversion of the CHamoru people to Catholicism.

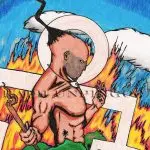

In this view, the world was divided into heaven, hell and earth. Heaven was a place deep within the earth, a paradise where food is plentiful and those who end up there, need not ever worry again about the necessities of life. Hell was a place called Sasalaguan, which is the realm of Chaife, a God who keeps souls in cages and regularly subjects them to forms of fiery pain and agony.

According to this foreign adaptation of the CHamoru world view, the spirits that roam the earth either did not exist or are evil. The division of the world into heaven, hell and earth makes clear the routes for which the souls of the dead are supposed to travel. Those who are good go to the paradise beneath the earth, where they no longer have any cares in the world. Those who are bad go to Sasalaguan where they have to endure the eternal torture of Chaife. There are not supposed to be any errant spirits wandering the earth pestering or assisting the living, and if you encounter any that do, they are evil and are ti anggokuyon (not trustworthy).

Additionally, Puntan and Fu’una (the brother and sister from the CHamoru creation myth) and Chaife were classified as Gods. They possessed incredible powers to shape the world and affect the lives of humans, and therefore existed as deities far removed from the lives of CHamorus, belonging to other realms. In terms of heaven and hell it is obvious to see the Christian influence in this world view.

The act of elevating figures such as Fu’una, Puntan and Chaife to the level of Gods or devils made it much simpler to Christianize the CHamorus. It simply became a matter of placing God as their savior alongside (or in place of) their other Gods, and convincing them that the Christian God is a stronger and more generous God.

Creation of the world

For CHamorus prior to Spanish colonization, this sort of divided world, with Gods and divine detached entities didn’t make sense. When CHamorus were asked by Spaniards Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora and Pedro de Talavera in 1602 about who had created their world, or their universe, the heavens and the earth, their answers didn’t seem to indicate the existence of any Gods or divinity. They responded saying that such searches for who or what God made these things was foolish, for they had made themselves. Furthermore, as CHamorus plant and harvest from the tåno’ (land), or fish from the tåsi (ocean), who is to say that they have not made themselves?

While the Europeans interpreted these statements to be ridiculous and the babblings of a savage but vain people, CHamorus believed in a singular world and their statements make perfect sense. The world was not one divided into Gods and humans, or even i manlå’la’ (the living) and i manmåtai (the dead). Rather all spirits and people lived in the same plane of existence. So when they spoke of Fu’una and Puntan creating the world, CHamorus weren’t referring to Gods, but to Fu’una and Puntan as the first CHamorus, their earliest ancestors, who through blood and genealogy are bound to all CHamorus. All that is, all that exists, is a testament to the cooperation between the ancestral spirits of CHamorus and those currently living. Since those who made the world are of us, and we are of them, then we all made the world.

A singular world

A version which is most likely close to what Ancient CHamorus believed prior to Spanish colonization, is that the world which Fu’una and Puntan created is a singular world, where all spirits and people, living and dead, live and exist together. A person who passes away does not go to another place, meaning another world or another realm, but remains in the world of its relatives, and is transformed to its ante (spirit).

Those who passed away were continued to be treated as members of a clan or a family, and in fact were given a more respected and revered status. As part of the living, these family members were depended upon to help do the physical labor of planting, harvesting, fishing, raising families, fighting wars, and singing to keep a family’s history alive. As part of the dead, they could no longer participate in these activities, but nonetheless gained power over the natural and spiritual forces of the world, and could intervene on behalf of the living. They could protect the family, bring good fortune or success, and even on occasions bring tragedy and pinadesi (suffering).

The world around CHamorus was therefore populated with the spirits of their ancestors, and everything from a good catch in fishing, a violent and painful death, a poor harvest, or success on the field of battle could depend largely on whether one pleased or displeased those spirits. The spirits were thought to live close to their relatives in death, either in the home or on a family’s land.

In this view, Fu’una and Puntan were not Gods of CHamorus, meaning they were not beings which existed fundamentally apart from CHamorus, distant and detached. Rather, Fu’una and Puntan would have been ancestors, the first CHamorus, their earliest ancestors. Other taotaomo’na or noted spirits or mythical figures such as Maga’låhi Gadao or Gåmson (octopus), would not be considered demigods, despite their incredible power, but would instead be considered distant ancestral relatives to certain clans.

The idea that CHamorus thought of their world as singular and that those they requested helped or aid from in protecting their families, their homes and their lives were not Gods, but rather spirits they believed to live among them, is supported by the absence of idols or large scale structures or statues which were meant to worship absent deities. The only icons of supernatural power which CHamorus collected or revered, were the skulls, called maranan uchan, of their ancestors, which they respected and treated as members of the family, in hope that they would in death as they had in life, continue to support and protect the family.

As part of the same world, these spirits could be communicated with, offended and beseeched in times of need. These spirits could defend the family from another family’s spirits. They could influence the tides, the moon, and the abundance of a harvest. They could also help bring valiant exploits to a family, by helping them in battle, or helping give them luck, strength or skill in mental and physical competitions.

Similarly, to keep yourself safe in moments of danger, you would not cry out to Gods for help, but rather cry out to favored deceased relatives. Ancient CHamorus in a crisis would shout the names of their deceased relatives imploring to them, that if they ever loved their family, they would help this person right now!

Earth, heaven and hell

The difference between these two world views depends largely on what you believe happens to people when they die. Where does their spirt go, and what does it become?

In terms of a divided world, a soul’s destination was determined by what kind of life they lived, meaning if they had been moral or immoral, done good or bad things in their lives. If they were a good person, then they would be taken to the paradise within the earth. If they lived a wicked life, their spirit would end up in Sasalaguan, where they would become the property of Chaife, and either end up being stewed eternally in a fiery cauldron, or beaten mercilessly atop a flaming anvil.

In a singular world, CHamorus believed that how they died, rather than how they lived determined what their afterlife would be as taotaomo’na. How you would die, depended largely on how well you met your kinship obligations, whether or behavior was gaimamåhlao (with shame), as well as how well you showed deference and respect to your ancestors. If someone met a peaceful and comforting end, surrounded by their family and friends, it meant that they had clearly shown to all that they had kept their obligations to both the living and the dead, and in turn their ancestral spirits had ensured that they were protected and cared for. Upon death, the spirit of such a person would return to the world and reside close to its descendants.

For those who died painful and lonely deaths, it meant that in their interactions with either the spirits or the living, they had clearly offended their ancestors, and in turn had lost their protection and aid. For these that met angry and tragic ends, they would become spirits far away from their families, usually isolated deep in the halom tano’ (jungle) or in liyang siha (caves) where few traveled. Over time, these spirits would become lalålu (angry) and mala’et (bitter) over their spiritual banishment or perhaps over the tragic way that they had died, and would become playful or vengeful spirits. They would possess, haunt or play tricks on those who entered into their territory.

Over time, the spirits which aided CHamorus, and whom they venerated, prayed to and celebrated in their homes and in their social rituals, would be replaced by Catholic saints. At the same time, those spirits which were thought to be angry and cause trouble for those still alive, were soon thought to be mere devils and demons, and were called taotaomo’na.

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

Russell, Scott. Tiempon I Manmofo’na: Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 1998.

Souder-Jaffery, Laura Marie Torres. Daughters of the Island: Contemporary Chamorro Women Organizers on Guam. 2nd edition. MARC Monograph Series No. 1. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1992.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.

Topping, Donald M., Pedro M. Ogo, and Bernardita C. Dungca. Chamorro-English Dictionary. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1975.