Historic descriptions

There is a dearth of written accounts of ancient CHamoru burial practices, but from the few historic descriptions available, the burial customs and rituals were elaborate.

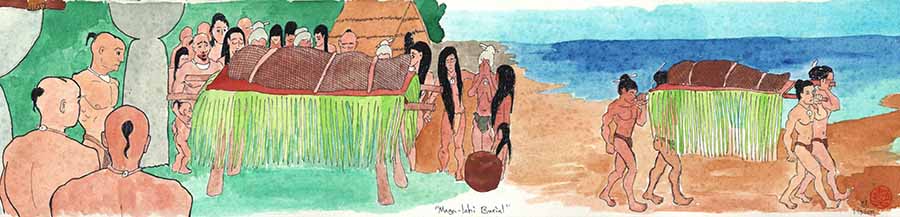

Spanish friar Fray Juan Pobre de Zamora, who lived among the CHamorus in Rota in 1602, had witnessed the funeral of a high-ranking CHamoru leader named Soom from the village of Atetito. According to Pobre, the decaying body was wrapped in a woven mat and placed on a scaffold of palms and trees. Other village leaders in attendance then gathered around the body, weeping and wailing. The body was then lowered from the scaffold and carried to the beach, where it was placed in front of the house of the highest-ranking male relative or heir. The deceased was then buried in a grave and covered with a new mat. Posts were placed at the corners of the grave to erect a small platform, upon which other new woven mats were laid. When the burial was complete, the mourners gathered at the deceased’s house for a feast.

The Jesuit missionary Fr. Diego Luis de San Vitores also described CHamoru burial practices in the early years of the Catholic mission. According to San Vitores, funerals were remarkable, “with many tears, fasting and a great sounding of shells.” The mourning period would last about a week or more—depending upon the social status of the deceased—with meals being shared around the grave.

The grave itself was decorated with flowers, palms, shells and other valuables. The deceased’s mother would cut off a lock of the individual’s hair as a memento, and count the days of her loved one’s death by tying a knot on a cord around her neck.

For high-ranking CHamorus (chamorri), funerals were more intense: the streets would be decorated with palms, arches and other funeral structures; as signs of grief, coconut trees would be uprooted, homes burned, and canoes destroyed, their torn sails hung in front of their houses. Songs of lament and praise for the deceased would be sung throughout the night. The grave would also be marked with the tools of the individual’s occupation—oars for a fisherman, lances for a warrior, or both.

In his account, Fray Juan Pobre also described the ritual for burying lower-ranking individuals. He wrote:

What they ordinarily do with their dead, however, is to cut the hair and wrap the body in a new mat, which serves as a shroud. Two of the deceased female relatives arrive, who are among the oldest women of the village, and lay pieces of tree bark or of painted paper on top of the body. Then they begin singing and crying simultaneously, asking so-and-so—calling him by name—‘Why have you forsaken us? Why have you departed from our sight? Why have you deserted the women who loved you so? Why have you abandoned your lance and sling, your nets and fishing boat?’ …More than two hours are spent in this manner, repeating these and other things. Amidst many tears, his relatives then embrace him and carry him away. Afterwards, they return to his house where each one drinks from a mortar filled with ground rice or with grated coconut mixed with water. The dead are buried in front of the most prestigious relative’s house.

Although neither Fray Juan Pobre nor Fr. San Vitores wrote much else about the burials, i.e., the placement of bodies within the grave or other funerary items interred with the body, archeological excavations throughout Guam have provided other important clues about how the ancient Chamorros treated their dead, even after burial.

For further reading

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation. Tiempon I Manmofo’na. Ancient Chamorro Culture and History of the Northern Mariana Islands. By Scott Russell. Micronesian Archaeological Survey No. 32. Saipan: CNMIHPO, 1998.

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1993.