Sottera/Sotteru: Teenagers

Change of social status

Derived from the Spanish term “soltera” for an unmarried female and “soltero” for an unmarried male, the Chamorized terms “sottera” and “sotteru” are used to describe youngsters once they have reach puberty.

The term is also often used to mean teenager, or young unmarried youth, in contemporary times on Guam. There is even a mixed paddling team event called “Sotteru/Sottera” that is for youth paddlers.

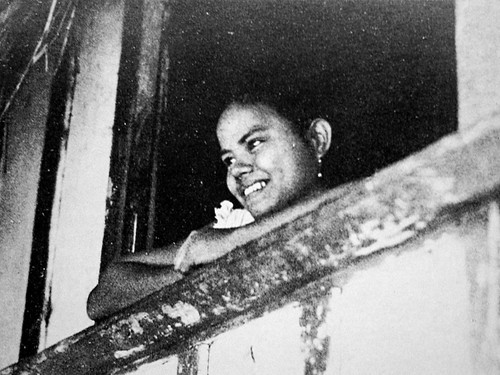

Girls are described as sottera once their menses begin. You might hear an adult say “Oh, she is sottera now” or “My daughter is sottera” once a girl begins menstruating which is a joyful occasion, though somewhat embarrassing for the girl.

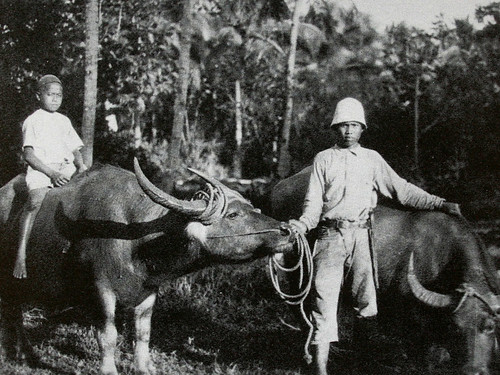

The term sotteru for boys is much used more rarely in contemporary society. When it is used, though, it would be to describe a manly appearing boy. For instance if a boy was muscular or had a beard at a young age, someone might comment, “He is so sotteru!”

For girls, becoming sottera also signals a change in her social status. Once she is sottera her parents might be more careful about making sure she is protected. Girls are often chaperoned when they leave the house, most commonly by other family members. Girls are usually allowed to go out with other siblings or cousins but are kept much closer to home than their brothers.

In the 1930s anthropologist Laura Thompson described a description of the customs of the times:

After the first menstruation, which usually occurs between the ages of 12 and 14 and is not marked by any ceremony, a girl is called soltera (sottera) until she married or becomes pregnant. A soltera in prewar Guam was not allowed outside the house alone at night. Shutters of rooms in which adolescent girls slept were frequently closed to guard them from prowlers. In fact even during the day most young girls rarely went out unaccompanied by a sister or other relative, especially in the villages.

Formerly, many parents were opposed to sending their girls to school, according to informants, because they did not want them to learn to write love letters. Although parents were eager that their girls should receive an education, many took them out of school at puberty because they did not want them to associate with boys.”

This practice of protecting unmarried daughters, though more relaxed than in the past, continues in contemporary times.

For further reading

Souder-Jaffery, Laura Marie Torres. Daughters of the Island: Contemporary Women Organizers of Guam. MARC Monograph Series 1. Mangilao: Micronesian Areas Research Center, University of Guam, 1987.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.