Organic Act of Guam

Granted Congressional US citizenship to the people of Guam

The Organic Act of Guam is federal legislation passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by US President Harry S. Truman on 1 August 1950. In general, the act established a non-military, civil government on Guam; granted congressional US citizenship to residents of the island at the time and their descendants; and solidified the island’s political status as an unincorporated territory of the United States. Formerly a Spanish colony, Guam was ceded to the US in 1898. Governance of the island was tasked to the US Navy. This military government was in power up through 1941 when Japan occupied Guam during World War II. After the war, the US military assumed authority over Guam in July 1944 and administered the island up to the passing of the Organic Act.

Throughout the US Naval Era, residents of the island were not US citizens, and their rights and liberties were therefore not concretely defined, guaranteed, or protected. A series of naval officers were appointed to the post of US Naval Governor of Guam throughout this period and they held complete executive, legislative and judicial powers. This system of government did not afford democratic rights to the population at large.

Consequently, written histories and popular understandings of the Organic Act have often characterized it as a generous gift from the US to the people of Guam and a resolution to imbalances in political power prior to the act’s passage. More recent histories, however, have begun to show that the Organic Act was achieved through decades of political mobilization among the indigenous CHamoru population rather than through US military and federal intervention. Further, the act and its success in establishing true self-government and equal rights for the people of Guam through US citizenship has come into question in the decades following its passage.

Petitions for civil rights date back to 1901

CHamorus expressed their protest to American rule in the earliest years of the Naval period. As early as 1901, and consistently in the years throughout the naval administration of Guam, numerous petitions were forwarded from Guam to the US Congress seeking self-government and US citizenship. These petitioners and their supporters argued that a military government was not suitable for the island, and sought political rights as well as US citizenship. They believed citizenship would guarantee them rights that the autocratic naval government had denied them. Protest to naval rule also took many other forms that were less direct, but it was the Guam Congress that served as the bedrock of organized political resistance.

The Guam Congress was formed in 1917 by US naval governor Roy Smith. The CHamoru men appointed, and later elected, as members of the Congress were convened due to growing concerns about the lack of political privileges among the local population. However, their role in the governance of Guam was merely advisory. Nevertheless, the congressmen quickly mobilized and used the Guam Congress as a forum to criticize the naval government, discuss civil rights and citizenship, and to mobilize politically.

The many attempts of the Guam Congress to address the island’s political matters culminated in a lobbying effort led by members of the Second Guam Congress. In 1936, Francisco B. Leon Guerrero and Baltazar J. Bordallo traveled to Washington, DC through the support of an island-wide drive for funds. By lobbying aggressively, they succeeded in getting Bill S. 1450 introduced in the US Senate. A companion bill, H. R. 4747 was drafted and submitted to the House of Representatives. The proposed legislation would have granted US citizenship to the people of Guam. The bill was passed in the Senate, however, it failed in the House largely because of heavy opposition from the US Navy Department and the Department of State.

Efforts toward civil, self-government and US citizenship during the first 40 years of the naval administration were interrupted as Guam was colonized by yet another country. Japan occupied Guam from 1941 to 1944, but the US military returned and re-established the Naval Government of Guam in 1944. In the immediate years of the second US colonial period on Guam, many of the concerns about the island’s relationship with the United States would resurface.

Guam Congress Walkout, 1949

In the aftermath of World War II, one of the leading causes of conflict between the naval government and CHamorus was widespread land seizures by the US military, largely for exclusive use by the military for recreation, rather than toward the defense of the island. Additionally, discriminatory wages for CHamoru laborers working for the military were one-fourth the pay rate of American laborers performing identical jobs. The desire for US citizenship and self-government was reignited as many believed this would afford rights and liberties to end these imbalances.

Dissatisfaction with the military government reached an impasse in 1949. Exercising what they assumed was their power to conduct investigations granted to them in 1947 by naval Governor Charles Pownall, the Guam Congress began scrutinizing potential violations of an existing law mandating that business licenses only be issued to permanent residents of Guam. The question of whether the Congress held inherent subpoena powers arose when Abe Goldstein, a navy clerk suspected of violating the law by operating a clothing shop, refused to answer to the Guam Congress. A warrant of arrest was issued for Goldstein for contempt, but Governor Pownall ignored the warrant arguing that the Guam Congress did not have authority over navy employees. The subpoena issue became a catalyst through which the larger concerns of the CHamoru people about their relationship to the United States were addressed.

On 5 March 1949, after discussion on the floor of the Assembly, the Guam Congress unanimously approved “The Bill to Provide an Organic Act and Civil Government for the Island of Guam” to be forwarded to the US Congress. Through the bill, the Guam Congress demanded US citizenship and civil government. Following the passage of the bill, member Antonio C. Cruz motioned that the House of Assembly adjourn and not reconvene until the US Congress issued a reply or acted on the proposed Organic Act of Guam. This was the beginning of the Guam Congress Walkout of 1949.

Assembly member Carlos P. Taitano played an active role in ensuring that the walkout made a substantial impact beyond Guam. Taitano reported the incident by radiogram to two reporters from the Associated Press and the United Press International in the US mainland. Almost immediately after the walkout, some of the nation’s main print media sources, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Honolulu Star-Bulletin, began publishing stories about the walkout, calling the American public’s attention to the grievances against the naval government on Guam.

Taitano’s efforts proved instrumental in the success of the walkout. Just over two months after the walkout, President Harry Truman ordered that the Department of Interior begin plans to take over administrative authority of Guam from the Department of the Navy. Governor Pownall responded by firing thirty-four of the thirty-six members of the Guam Congress and replacing them with appointed members. Reactions to this were hostile in Guam’s villages, and there was widespread refusal to recognize the new appointees. On 4 June 1949, Governor Pownall announced his retirement and plans to vacate the post of naval Governor of Guam.

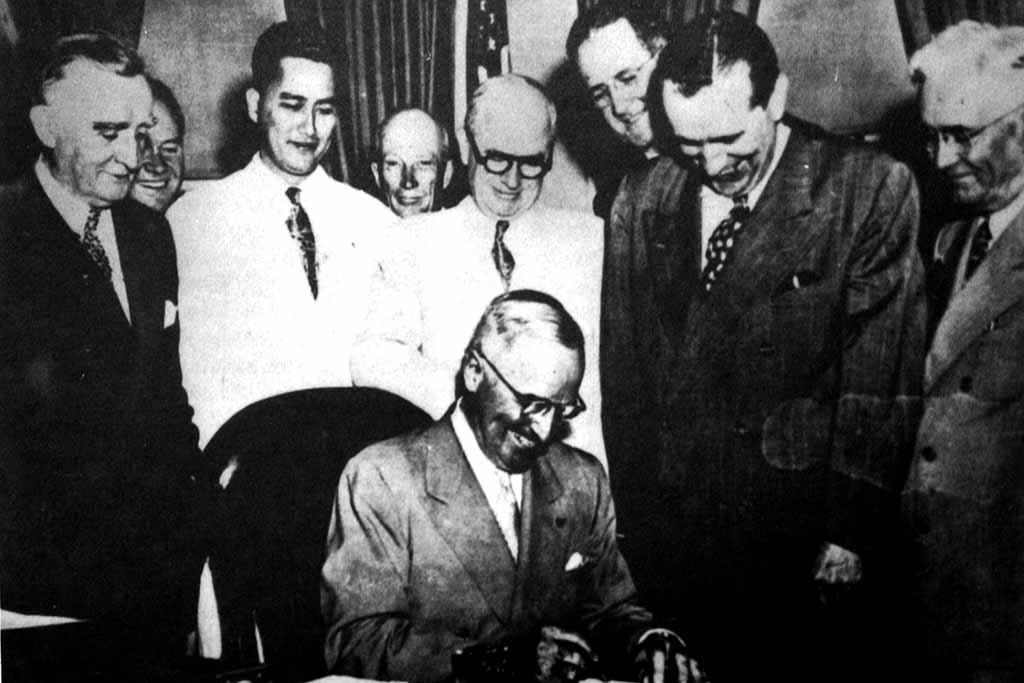

Organic Act signed, 1950

The Organic Act of Guam was signed into law by President Truman on 1 August 1950, and Taitano was the only CHamoru present at its signing as he was attending college in the area. At the time, the Organic Act was celebrated as a victory won after a long fight for self-government and citizenship that began nearly fifty years before its passage. Civil government had been granted through the removal of the Navy as the governing body of Guam. Residents of the island obtained US citizenship which many believed would stop unjust land condemnation, discrimination in the workplace, and other inequities that came with the former military government.

But questions soon arose as to whether civil government meant self-government. And even more questions arose as to whether the US citizenship granted in the Organic Act truly afforded the protections that many believed it would.

Struggles for control of Guam persist

In the decade that followed the passing of the Organic Act, issues such as military land-taking, federal control of land, a restrictive security clearance required for travel and trade in and out of Guam, and the federal appointment of Guam’s governor raised concerns for island residents. Attempts to address these concerns were made throughout the 1950s and 1960s. In August 1962, the security clearance requirement was lifted, opening travel and trade on the island. By 1965, Antonio B. Won Pat was sent to Washington, DC as the island’s representative at the federal level. He was finally recognized as a non-voting Delegate to the House of Representatives eight years later with the passing of Public Law 92-271 and an election by the people of Guam. In 1968, CHamoru demands to elect their own governor were addressed when the Elective Governor Act was passed and the first gubernatorial election took place in 1970.

These changes seemed to alleviate some of the imbalance of power between the US and Guam that had persisted after the Organic Act was passed. Many imbalances, however, remained. Even though the US military was removed from governing the island, Guam still did not achieve self-government. The governance of the island was simply transferred from the US Navy to the US Department of Interior, and indeed, the US Congress continues to have “plenary” or complete powers over Guam and its local government. The American citizenship for Guam residents has proven limited as residents of the island are not allowed to vote in US national elections and their elected representative to Congress still cannot vote on the House floor. And finally, stipulations that the US Constitution does not necessarily apply to Guam have increased questions about whether the citizenship granted in the Organic Act is equal to that of other Americans in the United States.

In 1968, Guam Senator Richard Taitano introduced legislation calling for a comprehensive review of the Organic Act noting that the people of Guam had never been consulted on its passage in 1950. Senator Taitano’s efforts led to the first Guam Constitutional Convention which convened forty-three delegates to explore possible amendments to the Organic Act. The delegates believed that improving the existing Organic Act was the best course of action, rather than seeking a complete change in Guam’s political status. The convention resulted in five recommended amendments to the Organic Act:

- Removal of the Secretary of the Interior’s oversight of Guam;

- Inclusion of off-shore waters and submerged lands in the jurisdiction of Guam;

- Just compensation to the people of Guam for land condemnation;

- Restoration of employment preference for CHamoru people in federal jobs; and

- Repeal of stipulations in the Organic Act prohibiting manufacture and transactions of marijuana.

The recommendations were forwarded to the US Congress in July 1970. A letter was issued acknowledging receipt of the proposed amendments, but no efforts were made to address them in Washington.

While the first Constitutional Convention was unsuccessful in its attempt to amend the Organic Act, it highlighted many ongoing concerns and problems rooted in Guam’s relationship with the US. These concerns led to the formation of a Special Commission on Political Status established by the 12th Guam Legislature from 1973-74. In relation to the Organic Act in particular, the commission noted that the existing act did not permit the people of Guam to effectively manage their own affairs.

The 13th Guam Legislature enacted legislation forming another Special Commission on Political Status from 1975-76. This commission was tasked with finding solutions to basic social, economic and political problems on Guam, highlighting shipping, immigration, restrictions preventing Guam’s participation in international organizations, economic restrictions, and the Organic Act in its entirety as elements of federal control on Guam that needed to be removed.

Rather than pursuing a specific political status such as independence, statehood, or commonwealth, the commission’s goal was to explore changes to various aspects of the existing relationship with the US toward creating something entirely new. Delegate Won Pat, however, sought a different route in Washington, DC. Won Pat instead proposed that Guam make recommendations about political status options and changes for the Organic Act of Guam. Although Won Pat never advanced his bill to hearing, his actions created tension in his relationship with the commission on Guam.

The tension between Won Pat and the Special Commission on Political Status continued as the Washington delegate pushed for a second constitutional convention with a goal of writing a constitution for the island. The commission opposed the process arguing that political status should be defined first and the drafting of a constitution should follow. Federal officials in the US responded by dictating that Guam should take what it could get. Amid protests from the commission, the federal government proceeded with a constitutional process informing Guam that political status was a different issue that should be addressed separately. The process outlined by the US government was extremely restrictive in the mandate that any constitution drafted and ratified by Guam not change the existing federal-territorial relationship. This left Guam no power over key matters such as land and immigration.

The restrictions placed on a potential constitution for Guam sparked intense debate on the island in the years from 1977 to 1979. Several CHamoru activist groups mobilized to fight efforts toward a constitution that they felt was merely a new Organic Act that perpetuated the status quo. Other groups formed in support of the constitution arguing that continued and closer relations with the United States were favorable. In the midst of these debates, a draft constitution was completed and presented to Guam voters in 1979. Ultimately, the draft constitution was overwhelmingly rejected by 10,247 voters, or just over 80 percent of island voters.

Commission on Self-Determination and the Guam Commonwealth Act

The rejection of the draft constitution for Guam in 1979 did not end the quest for political status change on Guam. Various attempts were made well through the close of the 20th century to address the limitations of Guam’s status as an unincorporated territory. In 1980, the Guam Legislature created the Commission on Self-Determination for the People of Guam. The commission was formed in response to the failed constitutional conventions with the task of determining the desires of the people of Guam with regard to their political relationship with the US. The commission formed various task forces to explore different political status options and then attempted to educate the public about each option. Finally it held two plebiscites to determine the people’s choice of political status in 1982.

In the first plebiscite the voters were to select their desired political status from seven choices: Statehood, Independence, Free Association, Territorial Status with the US, Commonwealth Status with the US, Status Quo, or Other. The second plebiscite that year was a runoff between the two highest results from the first vote: Commonwealth and Statehood. The people of Guam ultimately voted in favor of pursuing commonwealth status for Guam, much like the political status of the present-day Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Following the votes, the Commission on Self-Determination produced the Draft Commonwealth Act and forwarded the act to Congress.

The latter decades of the 20th century are remembered in large part as the “Commonwealth Now” era. The pursuit of commonwealth status was a leading priority for Guam’s elected leaders, both on island and in Washington, DC throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Throughout those decades, strong lobbying efforts attempted to advance the Draft Commonwealth Act. The Act was introduced in the US Congress four times by Congressmen Ben Blaz and Robert Underwood. Provisions for CHamoru self-determination and mutual consent in the draft act, however, were consistently opposed under both the Bush and Clinton administrations, and the Draft Commonwealth Act of Guam never made it out of committee.

The Organic Act in the 21st Century

The failure of the Draft Commonwealth Act in the US did not end the quest for political status change. This quest continues in the present. As has been noted by Dr. Robert Underwood, former Congressman of Guam, “At times, this desire will appear dormant while it will spring to life as it did in the 1930s and 1940s and in the 1970s and 1980s.” Guam entered into a relative lull in its pursuit of political status change in the late 1990s and into the early years of the 21st century. More recently, however, debates about the island’s political status and the lack of self-governance that Guam holds as a colony of the US have become a top issue on the island.

Recent plans by the US military to expand its presence on the island have increased concerns about military land acquisition and immigration, as well as economic, environmental and socio-cultural impacts. These were some of the same concerns that led the island to fight for and achieve the Organic Act of Guam those many decades ago. Although once celebrated as a victory for Guam, and one that was won through many efforts among the island’s people, Guam continues in an ongoing struggle with the US for full self-government and equal citizenship. The extent to which the Organic Act was adequate in achieving that, as well as the act’s ability to address the broader political aspirations of the people of Guam remains debatable.

e-Publications

The Organic Act of Guam and Amendments are available here. Courtesy of the Micronesian Area Research Center (MARC).

For further reading

Ada, Joseph, and Leland Bettis. “The Quest for Commonwealth, the Quest for Change.” Kinalamten Pulitikåt: Siñenten I Chamorro (Issues in Guam’s Political Development: The Chamorro Perspective). The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1996.

Hattori, Anne Perez. “Righting Civil Wrongs: The Guam Congress Walkout of 1949.” In Kinalamten Pulitikåt: Siñenten I Chamorro (Issues in Guam’s Political Development: The Chamorro Perspective). The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1996.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1995.