Men’s Roles

Protectors and providers

Mens’ role in societies have always been that of protector and provider. In the Mariana Islands, a change in the level of male authority was manifested with the transition from a matrilineal society to a bilateral society enforced by the Spanish after colonization beginning in the 17th century to conform with Spanish society.

In ancient Guam, men and women were equally important, serving complimentary roles to provide for the entire community. Men handled such physical activities such as toolmaking, warfare, canoe building and navigation and off-shore fishing. Women took care of the household, did weaving, food preparation, pottery making and inshore fishing.

Decisions made for the clan (extended families grouped together to form a hamlet or village) were made through consensus by a village council composed of the highest ranking males and females of the village. Men were more visible in their public leadership roles, but women were influential even if they were not at the forefront. The maga’låhi (highest ranking male) was the leader of the clan complemented by a maga’håga, the highest ranking female of a clan.

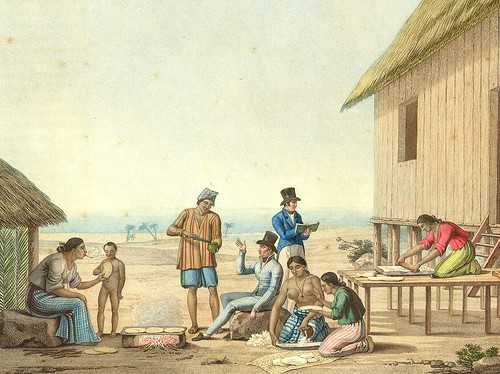

European observations

French explorer Louis Claude de Freycinet led an expedition in the Pacific that would eventually lead him to Guam in 1819. Freycinet recorded cultural and social practices of the ancient Chamorros as told to him by locals and made several observations of the Chamorro people during his few months stay in the island gathering scientific and ethnographic data.

On ancient Chamorro practices he noted that:

… by virtue of his physical strength and courage, the native male was destined at birth to navigation and warfare,” but because he was away from home for long periods, children were left to the care of their mother; therefore, becoming more endeared to their mother.

Women were heads of households in ancient Guam and during the time of his visit this practice continued. He noted that it was not uncommon to see women “river fishing and even tilling the soil” while still attending to their duties of running a home, but also observed the men’s roles:

… in former times the two sexes worked together and shared the tasks of fishing and agriculture. On the other hand, the building of houses and canoes, navigation, the upkeep of roads, and conveyance that offered any difficulties, were areas in which men played the main role.

Spanish mandated paternalism

Under Spanish rule, authorities recognized men as heads of households. While the Chamorros appeared to outwardly abide by this rule, it was not the reality in homes where women still maintained control.

A royal edict issued in 1741, mandating and facilitating paternalistic practices, actually created a dynamic that allowed women to remain the primaries at home, but men were established as the top of the hierarchy of family. The orders were meant to govern how people lived their lives, pushing patriarchal principles.

It stated that women were not to do work “contrary to their sex” and men must be given land to farm and work on. The establishment of the låncho (ranch) began. The orders then led to instructions for village officials one of which stated “not to allow any native to marry, whoever he might be, unless he first possesses a house in which he can live with his wife.” Because a man was legally obligated to raise food for his family’s subsistence, he was away from home for days at a time and the women were left to run the house in his absence.

When the United States took control of Guam in the 20th century, Chamorro society was even further transformed into a cash economy. Again, Guam’s residents faced an administration that legislated patriarchal values. Colonial dynamics allowed for the father to be legally recognized as in charge of the home, but (as with the Spanish) within the walls of the household, beyond the public gaze of authorities, women still ruled.

American anthropologist Laura Thompson was contracted by the US Navy in pre-war Guam to compile empirical data of Chamorro culture. Thompson conducted her research in the 1930s and documented that:

The father is usually the head of the family. He is responsible for and directs its economic activities. The mother, however, holds a dominant position in the home. It is she who usually controls the purse strings; she brings up the children and exercises a strict control over them even in adult life. She is responsible for the health of the family and she directs its religious observances (which are to a great extent also its social activities).

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de. An Account of the Corvette L’Uraine’s Sojourn at the Mariana Islands, 1819. Translated by Glynn Barratt. Saipan: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2003.

Herman, RDK. “Guam: Inarajan – Native Place: Village.” Pacific Worlds, 2003.

Souder-Jaffery, Laura Marie Torres. Daughters of the Island: Contemporary Women Organizers of Guam. MARC Monograph Series 1. Mangilao: Micronesian Areas Research Center, University of Guam, 1987.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.