Mampostería

Lime mortar and stone construction

The Spanish introduced cal y canto or lime mortar and stone construction to Guam. This includes the rare de silleria or dressed cut stone, and the more common mampostería.

Mampostería is stone and mortar construction, which is a Chamorro method of construction adapted from the Spanish building method. In its simplest form, mampostería ordinaria, masons mortared together stone rubble walls, stone by stone, upon bedrock or a compacted sand, earth, or stone foundation. In the rarer, mampostería cantería, cut stones with one flat outer face were mortared to the interior and exterior walls of a structure. In between these flat faced outer stones, rubble and mortar were used for filling the thick walls. The mortar was forty percent slaked lime or potdridu, and sixty percent sand mixed with water.

Masons finished the structures by plastering and finally whitewashing the interior and exterior surfaces of the buildings, including the exposed wall timbers. They made the whitewash of lime and water. The aplanådu (plaster) was primarily a slaked lime (fifty percent), sand (fifty percent), and water mixture. In Mexico and in the Philippines, the masons added a vegetable binder to make the mortar stick better and to make the plaster more water resistant. It seems likely that Guam’s masons added a light sugar cane syrup.

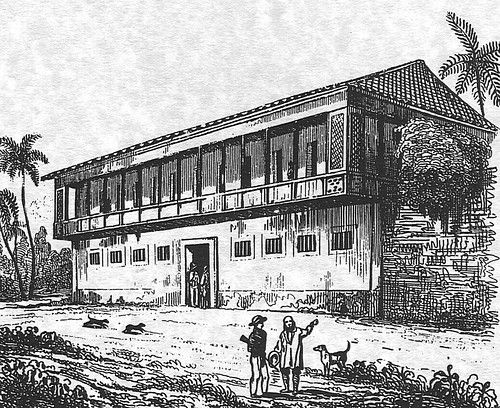

Chamorros called the mampostería houses budega structures. Budega refers to the mampostería storage area or cellar that formed the foundation. The budegas were seldom higher than six feet, seven inches tall. The workers built the entire house frame and the roof before filling the space between the supporting posts with thick walls of unshaped rocks bonded together with mortar. They buried the ifet (Intsia bijuga) posts in the wall but the ifet beams were left exposed. Rows of ifet posts, through the center of the budega, supported the floor framing. The Chamorros covered the small windows of the thick masonry walls of the budega with wooden shutters. For security, the government buildings had grilles made of heavy bars placed in the windows of budegas. The size of the windows in the mampostería walls was limited because the larger the opening, the more it weakened the wall. Masonry buildings had heavy wooden doors.

In the best houses, the Chamorros built an ifet wood frame house above the budega for their living quarters. The interior stairs were likely made of ifet wood. In some houses there may have been a wooden staircase from the budega to the interior living rooms of the house as well. The living quarters built above the budega were usually of wood or tabique interior and exterior walls, because they were safer than masonry during earthquakes. Tabique is a wet wall construction composed of thin strips of wood or bamboo laths plastered over with mud, clay or mortar.

Although there were some mampostería second floors in houses and government buildings, usually the upper story supported wood frame rafters and a roof. The mampostería buildings had either thatch or teha roofs. A teha is a barrel tile or curved terra-cotta earthenware roof tile. The terra-cotta roofs contrasted sharply with the whitewashed buildings. Although people manufactured some tile in Guam, they imported most of the tile used in the Mariana Islands. Woven mats or a canvas ceiling hid the kisami (quisame) or attic space below the sloping roof. The upstairs windows were taller and had sliding wooden shutters or windows of translucent capiz (Placuna placenta) shells.

The most common såtge or floor for the second story was polished ifet wood planks supported by ifet joists connected by wooden pens. Some bodega floors were raised ifet plank floors, while others had a ladriyu floor, a plain mortared floor, or just compacted earth. Ladriyu are unglazed clay tiles or flat bricks used for a variety of construction purposes.

Stairs, terraces and porches

The mampostería houses usually had massive stone stairways on the outside of the houses. The steps to these houses frequently went from the yard to a terrace or bátalan that connected the house to the kitchen. This usually was a solid terrace of walled masonry filled with earth, and capped with paving stones or an esplanåda. In less expensive houses the bátalan could take the form of a boardwalk or wooden bridge. Spanish fortifications in Guam had esplanådas that served as a platform for cannons. They put each paving stone in place with a mixture of sand and mud instead of using mortar.

In addition to the bátalan many mampostería houses had a simple raised masonry porch or totta. Usually, the open porch had a railing supported by posts or a balustrade. Balconies surrounded the second story of the mampostería houses. The balconies were opposite the windows. Except for the gable end of houses the balconies were usually covered by an overhanging roof. A balustrade surrounded the balcony.

People in Guam built mampostería homes, fortifications, churches, schools, and other government buildings. These structures were designed to withstand Guam’s typhoons and earthquakes, and indeed some have survived into the twenty-first century.

By Lawrence J. Cunningham, EdD

For further reading

Crofts, George D., and Emilie G. Johnston. “Governor Gregorio Santa Maria Saves and Enlarges the College of San Juan de Letran.” Guam Recorder 5, no. 1 (1975): 24-28.

Driver, Marjorie G. “Government House in Need of Repair.” Guam Recorder 4, no. 2 (1974): 16-21.

Ramirez, Anthony J., ed. Freedom to Be: 40th Anniversary of the Liberation of Guam. Tamuning: Fiestan Guam Committee, 1984.

Ruth, H. Mark, Jack B. Jones, and Morris M. Grobins, eds. Guidebook to the Architecture of Guam. Taipei: Guam and the TTPI Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, 1976.

Safford, William E. A Year on the Island of Guam: An Account of the First American Administration. Washington, DC: H.L. McQueen, 1910.