Luís de Torres

Guam-born sargento mayor

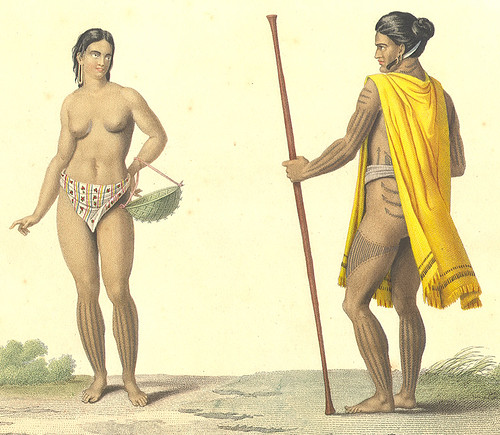

Guam of the late-18th century only had a population of about 2,000. The CHamoru people were in a state of recovery following many years of the ravages of disease and war. The Spanish-CHamoru War of the late-17th century had ended all resistance against the Spanish Crown, but Western diseases—diphtheria, smallpox, and influenza— also caused widespread destruction. By the time the Spanish conducted the 1786 census, it was reported there were only 1,318 indigenous CHamorus.

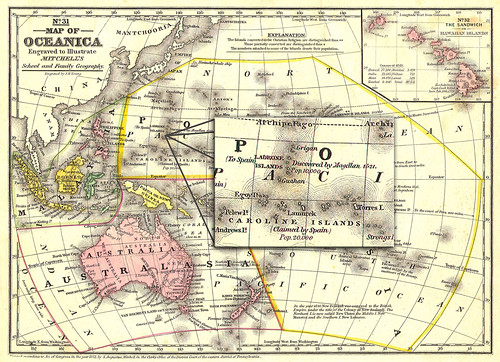

Conditions would slowly improve, most notably under Spanish Governor Joseph Arlegui y Loez’s eight-year tenure. The political changes ushered in by Arlegui led to the first village-level indigenous government. The Spanish also wanted to ease strained relations with the surrounding Micronesian islands. Historians note that in 1787 trading voyages from the Carolines to Guam were resumed. While the CHamorus and the Carolinians had previously traded such items as turmeric and shell belts, now the Carolinians bartered for iron and metal tools from Guam.

Regional contributions

A young Guam-born sargento mayor, Luís de Torres, made several undeniably noteworthy contributions to the region.

In 1788, a large flotilla of canoes from Lamotrek made its way to Talo’fo’fo Bay. Helping the Lamotrekese was Torres, who assisted the islanders in obtaining the goods they desired. After several months on Guam, the Lamotrekese set sail, but not before they promised to return to Guam the following year. They never did, and no one knew why. The mystery would not be solved for another 15 years.

By the early 1800s, the once lucrative Manila Galleon trade was coming to an end. Although the Spanish still held sway in the Marianas, American whalers and traders were plying western Pacific waters for the elusive sperm whale, fur seals, and trepang—sea cucumbers used by Asians gourmands in soups and by herbalists as an aphrodisiac. Most of the ships would stop at Guam to replenish stores and supplies.

In 1804, Torres chartered a barely seaworthy schooner, owned by English shipmaster Samuel W. Boll, Maria, and stocked it with oxen, hogs, and useful plants. Torres’s humanitarian intention was to travel to Lamotrek to not only rekindle old friendships, but to solve the mystery of why the Lamotrekese never returned to Guam. The Maria made its way to Woleai, one of the most prominent atolls of the Yapese outer islands — where Torres learned that a typhoon in 1788 must have wiped out the voyagers on their way back from Guam.

Re-established regional relationships

At Woleai, Torres left the livestock and plants. An English blacksmith, who had volunteered to teach his trade, remained at Woleai. Torres had once again re-established cordial relations with the islanders and trade would resume by 1805 between Guam and Woleai, Lamotrek, and Satawal. Unfortunately, the livestock were soon killed, the plants died out in the poor soil, and the Englishman, too, died shortly later.

Following Torres’ journey to Woleai, he became somewhat of a patron to all Carolinians to the extent that he appeared in Carolinian songs along with shipmate Thomas Borman (known in the songs as ‘Marmol’) that accompanied Torres. In November 1817, Otto von Kotzebue referred to the songs still being sung and the role of Torres and Carolinian connections to Guam being recounted. Early 19th century explorers from France, Russia, and Germany transcribed, extracted and disseminated considerable portions of Torres’ knowledge of the Carolinians, including their languages and geography. Scientist Adelbert von Chamisso in particular spent considerable time with Torres and as a result conveyed information on the Carolinians to Spanish authorities on Guam that they had lacked for centuries.

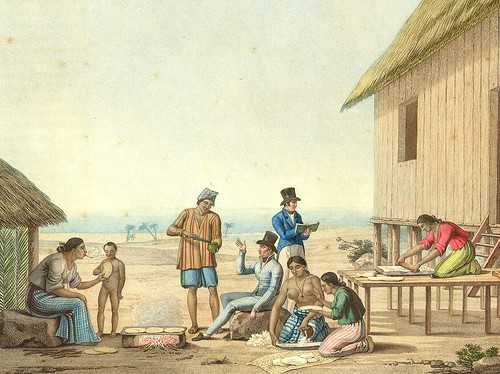

On 17 March 1819, the L’Uranie, captained by Louis Claude de Freycinet, anchored off Humåtak Bay and stayed for three months. The primary purpose of his stay at Guam was to gather scientific and ethnographic data.

Because of the long duration of the visit, and owing to the usual French intellectual curiosity, members of the Freycinet expedition compiled one of the most thorough scientific and historical descriptions of Guam of any visitors in the 18th and 19th centuries. Some of this information was based on the histories of Jesuits Francisco Garcia and Charles Le Gobien, but it was greatly amplified by data from interviews with CHamorus and Spaniards on Guam, particularly de Torres.

Another such scientific expedition, led by the Russian Ferdinand (Fedor) Petrovich von Lütke, stopped at Guam in February 1828. Torres offered his land at Orote Peninsula to the Russian scientists, who set up an observatory. Three months later, the French scientist, Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville, aboard the Astrolabe, made his way to Guam and anchored at Humåtak for four weeks. This would be the first of two visits the eminent Frenchman would make to Guam, with the other occurring in 1839. Torres was on-hand to inform d’Urville about Guam’s history and Micronesian customs. Torres became a revered patron to the outer islanders due to his benevolence, and he helped create a better understanding of the western Pacific for the Europeans.

For further reading

Dumont d’Urville, Jules-Sébastien-César. Two Voyages to the South Seas. Translated and retold by Helen Rosenman. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1992.

Hezel, Francis X., SJ. The First Taint of Civilization: A History of the Caroline and Marshall Islands in Pre-Colonial Days, 1521-1995. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1983.

Lévesque, Rodrigue. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vols. 1-2. Québec: Lévesque Publications, 1992.

Litke, Fedor Petrovich. Voyage Autour du Monde, 1826-1829. New York: Da Capo Press, 1971.

Rogers, Robert. Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press, 1995.

Sanz, Manuel. Description of the Mariana Islands, 1827. Translated by Marjorie G. Driver. MARC Educational Series no. 10. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1991.

Underwood, Jane H. “The Native Origins of the Neo-Chamorros of the Mariana Islands.” Micronesica 12, no. 2 (1976): 203-209.