Guam's Political Status

Table of Contents

Share This

Interpretive essay: Subject of controversy

Since the claim by Spain over the Mariana Islands in 1565 and the settlement of Jesuit missionaries and conquest of the CHamoru/Chamorro people in the 17th century, the control and ultimate political fate of Guam has been the subject of war and political controversy.

Today, Guam’s official political status is that of “unincorporated territory of the United States.” The people of Guam are US citizens and while they may acquire full political equality as individuals if they move to any of the 50 states, they are in a subservient political condition if they remain in Guam. They are unable to vote for president, select members of US Congress with voting power and congress can overturn any law passed in Guam and can decide which parts of the US Constitution apply to it.

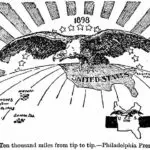

This political status came out of the transfer of the authority over Guam from Spain to the United States at the conclusion of the Spanish American War in 1898. Guam, along with Puerto Rico and the Philippines, were ceded to the US. In subsequent court cases heard in the US Supreme Court, these areas were deemed “unincorporated territories” as opposed to “incorporated territories.”

Basically, the US Congress is given plenary power over the territories as outlined in the Constitution’s Territorial Clause (Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2). Unlike incorporated territories, the US Constitution does not fully apply and unincorporated territories are not destined for statehood. For individual residents of the territories, there is no automatic grant of citizenship and no clear path to political participation. In the Treaty of Paris that gave Guam to the US, it simply said that the “political and civil rights of the native inhabitants will be determined by Congress.”

Without a path to full integration into the American union and with a Supreme Court decision that gave Congress nearly unlimited authority, political progress and fulfillment took a backseat to national security interests in Guam. As such, it took fifty years of local agitation and the Japanese Occupation (1941 to 1944) to get Congress to pass the Organic Act in 1950 that provided for a local civilian government and American citizenship.

The Organic Act provided for a measure of limited self-government that continues today and has been enhanced by congressional amendments that have added elected governorship, a non-voting delegate to Congress, a hierarchical judicial system similar to the states, and other improvements. But the ultimate fate of the island has yet to be decided and it is not clear how it will be decided and by whom.

Political Status Commission

Influenced by events in other territories like Puerto Rico and the emerging discussion of various political status options for the surrounding Micronesian Islands (part of the old Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands), I Mina Dosse Na Liheslaturan Guåhan/ the 12th Guam Legislature passed Public Law 12-17.

The law created a Political Status Commission to educate the island on various political status options. I Mina Tresse Na Liheslaturan Guåhan/ the 13th Guam Legislature passed legislation creating a new political status commission with an eye to holding a plebiscite in 1976. Guam’s political leadership was insistent on creating the opportunity for action since the surrounding islands, particularly the Northern Marianas, were getting serious attention from Washington DC in a series of negotiations that led to a new commonwealth. For all of its loyalty and years under the American flag, Guam was not getting the same deal as their neighbors to the north.

Unbeknownst to local officials, the Ford administration was prepared to discuss the possibility of a new political relationship with Guam under an arrangement no less favorable than that offered to the Mariana Islands. However, US Department of Interior officials were slow to move on the presidential directive that made clear the path to be taken. Guam held its political status referendum and the status “Status Quo with Improvements” won with 51 percent of the vote. Statehood received 21 percent and independence garnered five percent of the vote.

The direction of the island was not any clearer. Congress passed legislation authorizing Guam and the Virgin Islands to draft local constitutions to replace the Organic Act. This was seen as a progressive step, but did not alter the political status of Guam. A Constitutional Convention was called and after nearly two years of work, the electorate voted down the document in mid-1979. Many of its opponents argued that political status should come first, then the constitution.

Commission on Self Determination

This vote seemed to fuel new energy for the political status efforts of local leaders. In 1980, the Guam Legislature enacted a new Commission on Self-Determination (P.L. 15-128) and this was the body that was going to lead the way in terms of holding another election and implement the choice of the people of Guam. Immediately, the first issue that the Commission dealt with was deciding the “self” in self-determination. The discussion was no longer limited to which political status was preferable, but rather who was going to participate. Quoting United Nations documents, the Treaty of Paris (which referred only to political rights of native inhabitants), advocates of CHamoru self-determination steered the discussion in a new direction.

The commission held four referenda. The first two were to decide which option to pursue. Statehood and commonwealth won in the first referendum with commonwealth beating out statehood which was seen as impractical. The commission then drafted a commonwealth measure to present to Congress. Rather than having the document discussed in process, it was decided to prepare and ratify the document in Guam before submission. The draft was ratified in two votes in 1987 and included provisions that would limit immigration, hold a CHamoru self-determination process and allow for mutual consent in changing the document. These provisions became bones of contention when Guam representatives had to deal with federal officials. Voting on the provisions in advance of submission to Congress made it difficult to engage in any serious “give and take” in discussions with federal officials, whether they were in Congress or in the Executive Branch.

The administrations of Guam Governors Joseph Ada and Carl Gutierrez made Commonwealth Status the cornerstone of their federal relations portfolios.

The document was introduced in Congress four different times under the leadership of Congressmen Ben Blaz and Robert Underwood and received two hearings (1989 and 1997). Federal officials under the Bush and Clinton administrations were consistent in their opposition to CHamoru Self-Determination and mutual consent and the bills were never reported out of committee. The discussions between the Commission on Self Determination and federal representatives never yielded a final agreement.

In response to the lack of movement, the Guam Legislature created a CHamoru Registry for the eventual exercise of CHamoru self-determination with or without Congressional authorization. A new Commission on the Decolonization of Guam was established to move the process forward in advance of any formal discussion with the federal government.

Status questions unresolved

Public support and interest has waned and political leadership has been uninvolved in the process. Felix Camacho, governor from 2003-2010, wrote letters to Congress about a potential new constitutional convention, but has not been active in either the Commission on Self Determination or Decolonization. Guam Congresswoman Bordallo has been silent on the matter to date. Governor Eddie Calvo says he will take an active stance on decolonization and reconvened the Commission on Decolonization. Members of the Commission attended and testified at two United Nations regional seminars in addition to three Decolonization plenary sessions at the UN in New York. Commission director Ed Alvarez said funding is currently being sought for a public education campaign to be followed by an eventual vote.

Today, the political status of Guam is basically the same as it was at the time the island was ceded to the US by Spain. Guam remains an unincorporated territory that is not on a track to statehood. There are many incremental steps that have improved conditions and federal-territorial relations are governed more by domestic concerns like inclusion in domestic programs rather than disputes over authority that can be resolved through political status.

But the desire for political fulfillment certainty will always be a feature of Guam’s ongoing relationship with the United States. At times, this desire will appear dormant while it will spring to life as it did in the 1930s and 1940s and 1970s and 1980s. But the issues remain difficult. Should there be a formal mechanism like a plebiscite to consult the will of the CHamoru people?

As the CHamoru population of Guam dwindles to less than 50 percent, the issue seems more urgent than ever. Does Guam have the right to independence and self-determination as the United Nations claims all small non-self-governing territories do? Is this right rejected by federal authorities? What will get federal attention in the near future?

For further reading

Kinalamten Pulitikåt: Siñenten I Chamorro (Issues in Guam’s Political Development: The Chamorro Perspective). The Hale’-ta Series. Hagåtña: Political Status Education Coordinating Commission, 1996.

Willens, Howard P., and Dirk A. Ballendorf. The Secret Guam Study: How President Ford’s 1975 Approval of Commonwealth Was Blocked by Federal Officials. Mangilao and Saipan: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam and Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands Division of Historic Preservation, 2004.