Fort Soledad

Table of Contents

Share This

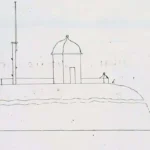

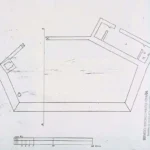

Fort Nuestra Señora de la Soledåd, c. 1810

Fort Nuestra Señora de la Soledåd, or Fort Soledad, the last of four Spanish fortifications built in the village of Humåtak/Umatac, is located atop a steep bluff called Chalan Aniti, or Path of the Ancestors. The fort provides a superior view of the village, the bay, the rugged coastline, and the imposing southern mountain range. The fort was constructed to strengthen the defenses of Guam’s most prominent Spanish-era bay.

Humåtak Bay served as an important supply station for ships crossing the vast Pacific Ocean during the era of the Acapulco-Manila galleon trade (1565 – 1815). With an increasing number of non-Spanish ships sailing through the Pacific in the last half of the eighteenth century, it became necessary to protect Spanish interests on the island. Fort Soledad helped to strengthen flaws of the other forts built along Humåtak’s coastline. Fort Santo Angel, located on the opposite side of the bay, was built in 1756 and had been badly damaged from years of pounding waves. Governor Alexandro Parreño (1806 – 1812) determined that the foundation supporting the fort was unsafe and had the fort dismantled. Fort San Jose, despite being newly constructed in 1805, was positioned too far north to adequately protect the entrance of the bay.

Although Governor Vicente Blanco (1802 – 1806) had described artillery that had been mounted on Chalan Aniti as early as 1803, it was not until some time during Parreño’s administration that the fort’s construction was completed and officially named Fort Nuestra Señora de la Soledåd, Our Lady of Solitude. In a document dated 1810, Parreño described the features of the newly built fort, which included a barbette, a guardroom for officers and troops, and an arsenal storeroom.

The fort faced the sea and was elevated eighty varas, or approximately 224 feet, above the bay. The esplanade was paved with flagged coral stones and was partially surrounded by a low parapet constructed of mampostería, stone and mortar. The fort could accommodate seven cannons that were to be fired on a fixed line over the parapet.

Unfortunately for Spain, the Mexican Revolution brought an end to the galleon trade. By 1815, the last Cavite ship returned to the Philippines from Acapulco, signifying the end of an era. Spain no longer had the means to maintain Guam’s fortifications and Fort Soledad was allowed to deteriorate. Treasure hunters expedited the fort’s destruction as they pulled up the floors in search of the fortune rumored to be buried at the site. After the Second World War, souvenir hunters continued to pillage the fort. The government of Guam, however, stopped the complete destruction of the fort and continues to protect the site as a public park.

The fort’s sentry post, overlooking the picturesque bay, has become an icon of the island’s beauty and the days of the Spanish Galleon trade. Today, the park is one of the most visited places in southern Guam. In the mid 1990s restoration efforts were made to the area’s stonework and more recently several beautification projects have been undertaken by the community to improve the historic landmark.

For further reading

Beaty, Janice J. Discovering Guam: A Guide to its Towns, Trails and Tenants. Tokyo: Tokyo News Service, 1967.

Degadillo, Yolanda, Thomas B. McGrath, SJ, and Felicia Plaza, MMB. Spanish Forts of Guam. MARC Publications Series 7. Mangilao: Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1979.

Driver, Marjorie G., and Omaira Brunal-Perry. Architectural Sketches of the Spanish Era Forts of Guam: From the Holdings of the Servicio Historico Militar, Madrid. MARC Educational Series no. 17. Mangilao: Richard F. Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1994.

Guam Department of Parks and Recreation. “Guam State Historic Preservation Office.”