Emmok: Revenge

Part of CHamoru reciprocity

The CHamoru expression inafa’ maolek (making it good for each other) expresses a core CHamoru value. A life of harmony is taken to be the highest form of human achievement by the CHamoru people. Harmony within the community, with the ancestors, and with the natural environment is understood to be the most important aspect of a meaningful adult life. Harmony is valued more than being right or even correcting a wrongdoing.

Emmok (revenge) is both a concept and a practice that appears in the inafa’ maolek conceptual constellation and cultural practices.

Another concept that helps give shape to the constellation of CHamoru cultural and philosophical values is reciprocity. Positive forms of reciprocity are chenchule (gifts of money or food) and ayuda (assistance or help), and negative forms entail revenge. Todu manatungo” (consensus) primarily among family clan leaders, plays an important role in the decision making process. Social position, rank, and senior age play a substantial part in maintaining social order and cooperation.

“Mamåhlao” (behaving with respect and deference) is highly prized; one of the worst things one could do is to publicly ridicule or shame another person. Thus, social pressure and other limitations are placed on the competition for rank and social status. Social harmony is not a constant. Just as one cannot always depend on nature, one cannot always depend on others. At times social interdependency totally breaks down. Feelings are hurt, someone is shamed, and conflict arises.

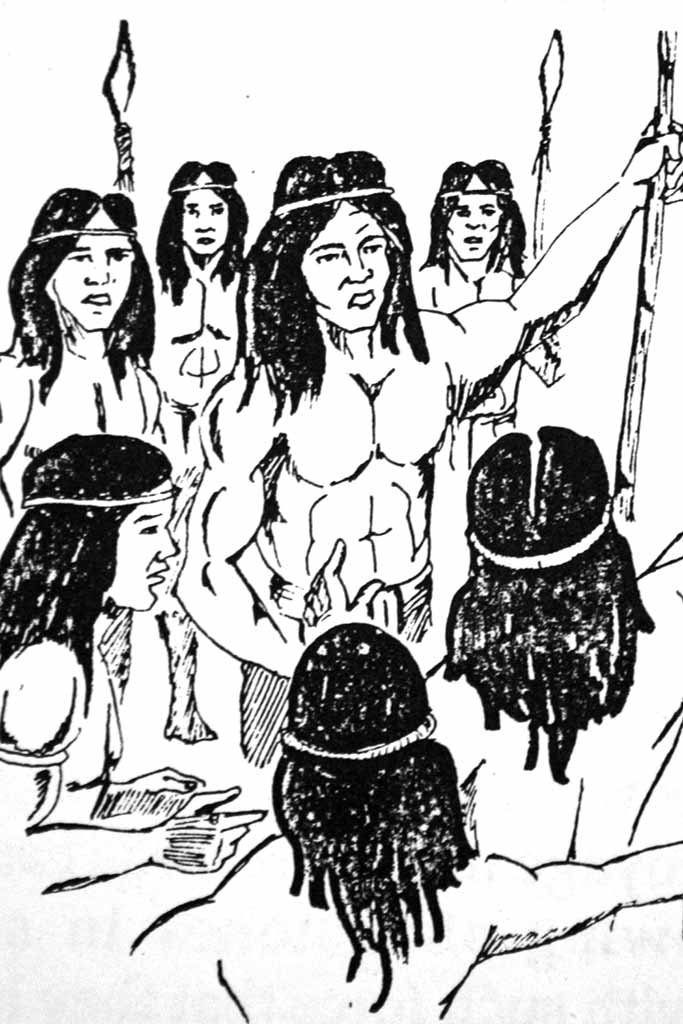

Warfare and revenge are part of the reciprocal relationship. Just as gifts require an exchange or repayment, so do insults and harms. Because the individual is interrelated with the family-clan, to insult or harm one is to harm all and may require conflict or vengeance. The ancient CHamoru wars were, as best we can gather, rather humane in that they did not go to the extreme of annihilating the whole clan. In ancient times, the conflict usually ended after someone was wounded or a few warriors were killed. Some form of payment, often tortoise shell money, could be used to sue for peace.

“Kantan Chamorita” (folk songs and proverbs) are primarily spontaneous and extemporaneous which reveals the value placed on the individual’s wit and intellect to hold forth when put on the spot. Some of the songs were recorded by anthropologist Laura Thompson in 1947. Although these songs are from the twentieth century, they have their roots in antiquity, and they express the importance of interrelatedness. An important example related to this concept is the following:

| CHamoru | English |

|---|---|

| An numa’ piniti hao taotao, nangga ma na’ piniti-mu. | When you hurt somebody, be expecting to be in pain. |

| Maseha apmamam na tiempo, un apasi sa’ dibi-mu. | For even if it takes time, surely you’ll pay for the pain you’ve caused. |

For further reading

Cunningham, Lawrence J. Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1992.

Driver, Marjorie G. The Account of Fray Juan Pobre’s Residence in the Marianas, 1602. MARC Miscellaneous Series No. 8. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1989.

Fritz, Georg. The Chamorro: A History and Ethnography of the Mariana Islands. Translated by Elfriede Craddock. MARC Working Papers no. 45. Mangilao: Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 1984.

Haverlandt, Ronald. Of Ocean Foxes & Guilty Wolves: The Beforetime People, Their Epic Response to Modern Power. Unpublished Manuscript. Micronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam.

Thompson, Laura M. Guam and Its People. With a Village Journal by Jesus C. Barcinas. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1947.

Underwood, Robert A. “What is a Family?” Pacific Daily News, 18 November 1979.